In many regions of the world, floods wreak havoc on communities and economies. Developing countries, in particular, bear the brunt of these disasters, often lacking robust infrastructure and the monitoring networks needed for accurate flood predictions.

Floods are the most common natural disaster and nearly 1.5 billion people, or some 19 percent of the world population, face substantial risks from severe floods, causing around $50 billion in annual global economic damage.

Now a groundbreaking study published in Nature unveils a promising solution: harnessing the power of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance flood forecasting, so communities can prepare properly.

‘AI helped us make improvements to provide more accurate information on riverine floods up to seven days in advance,’ commented Yossi Matias, Google VP of Research and Engineering. ‘This enabled us to provide flood forecasting in 80 countries, in areas where 460 million people live, and can help communities stay safe.’

The development, in the wake of AI weather forecasting, comes when human-caused climate change has exacerbated the frequency and intensity of flooding in many regions and the rate of flood-related disasters has more than doubled since 2000. ‘We were able to use AI-based forecasting to improve forecasts in regions in Africa and Asia to be similar to what are currently available in Europe,’ added Matias.

BEFORE AI

Traditional forecasting methods are computer models that rely on extensive data and measurements, such as the Copernicus Emergency Management Service Global Flood Awareness System, which is fed by measurements made by two orbiting satellites.

But these models have to be calibrated by what are called stream gauge networks, which measure the local water budget, making them less effective in watersheds that lack this infrastructure, posing a significant challenge for timely local flood warnings.

Indeed, ‘prediction in ungauged basins’ was deemed as the decadal problem of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences from 2003. However, the Association had to admit that, by the end of that decade, little progress has been made.

AFTER AI

Today, however, researchers led by Grey Nearing of Google Research report an AI-based forecasting model that demonstrates remarkable accuracy and reliability, even in regions without reliable measuring systems, up to five days into the future.

The reliability of these forecasts – created with colleagues at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, Reading, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, Leipzig, Germany, and the RAND Corporation, Los Angeles – rivals or surpasses the accuracy of nowcasts, or same day predictions, from Copernicus.

Moreover, the AI model excels in predicting floods with return periods of five years, that is the average time over which a flood of that magnitude will return, outperforming current methods designed for events with only a one-year return period. In other words, it is as accurate for bigger, less frequent, flooding events.

Today’s work suggests that AI can offer earlier warnings for both small and extreme flooding events, widening access to reliable flood forecasting, especially in developing regions.

WE NEED MORE DATA

AI is only as good as the data used to train it – in this case using 5,680 existing gauges to predict flows ungauged watersheds over a 7-day forecast period. The team puts in a plea to archive historical forecasts, stressing the importance of increasing the availability of data to roll out reliable flood warnings globally.

Populations in low- and middle-income countries make up almost 90% of the 1.8 billion people that are vulnerable to flood risks and the World Bank has estimated that upgrading flood early warning systems in developing countries to the standards of developed countries would save an average of 23,000 lives per year.

By providing earlier and more accurate flood warnings, AI technologies can help communities prepare and respond effectively to these increasingly frequent and severe natural disasters. By one estimate, for example, early warning systems could cut flood-related fatalities by around 40 per cent, and almost halve the economic impact.

FROM INDIA TO THE WORLD

The AI flood forecasting project began with a pilot in India’s Patna region in Bihar, where much of the population faces the threat of devastating floods. Various elements—from historical events, to river level readings, to the terrain and elevation of a given area—were fed into the forecasting models, which were honed over hundreds of thousands of simulations. Eventually, in 2018, Google could provide flood forecasts for public alerts.

Following the success in India, Google gradually expanded its forecasts across the country and into Bangladesh, providing alerts to more than 240 million people. ‘At the time, we could provide forecasts up to 48 hours in advance,’ said Matias.

Using a new model of inundation and combining advances across all models enabled further expansion to cover 360 million people in India and Bangladesh.

Then, to create a global model, the team harnessed global data sources with a goal of predicting floods even in regions that lack local streamflow measurements.

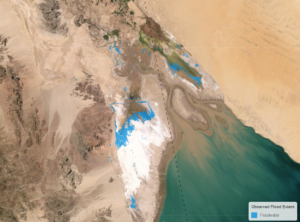

In 2022, Google launched the Flood Hub platform, which provided access to forecasts in 20 countries – including 15 in Africa – where forecasting had previously been limited. By the following year, it had added locations in 60 new countries across Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, Europe, and South and Central America, covering some 460 million people globally.

‘We are collaborating with the World Meteorological Organization to support early warning systems – and specifically the Early Warnings for All initiative,’ said Matias. This ‘aims to provide early warnings about climate hazards to everyone around the world by 2027.’