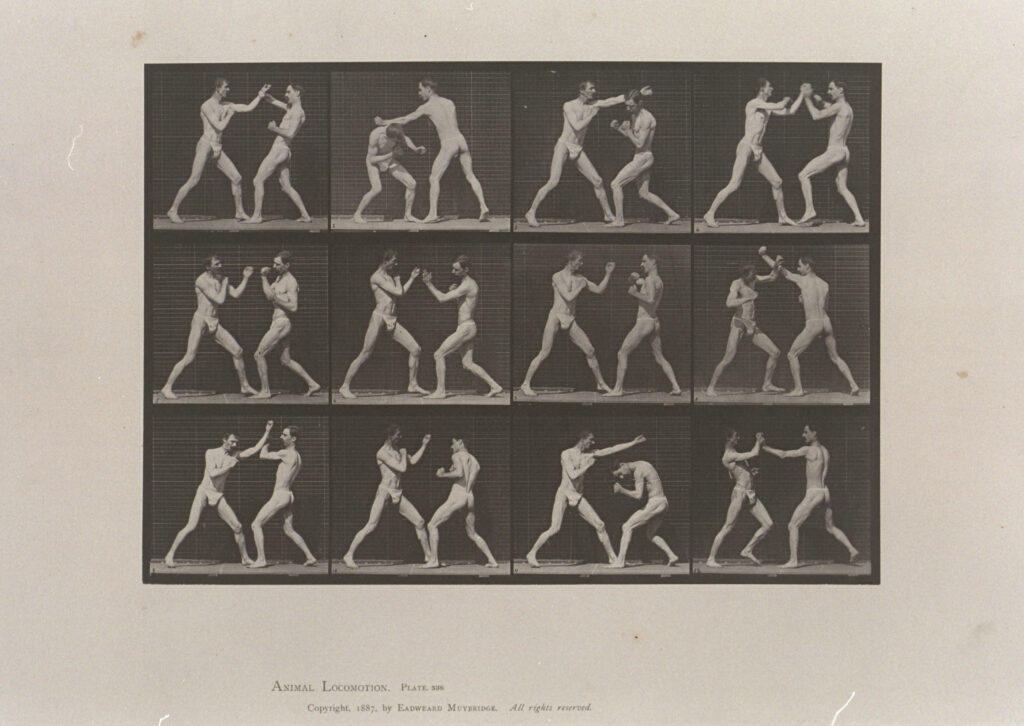

When the Prince of Wales told the photographer Edward Muybridge ‘I should like to see your boxing pictures,’ few could have predicted the depth of influence they would exert over the sport known to Victorians as ‘the sweet science’.

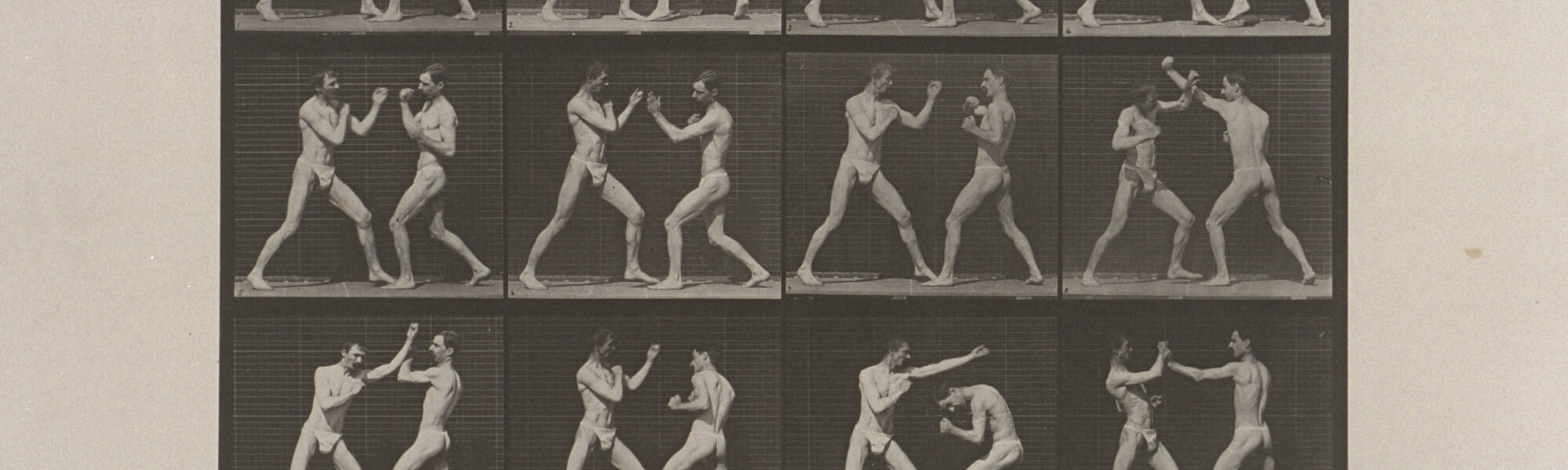

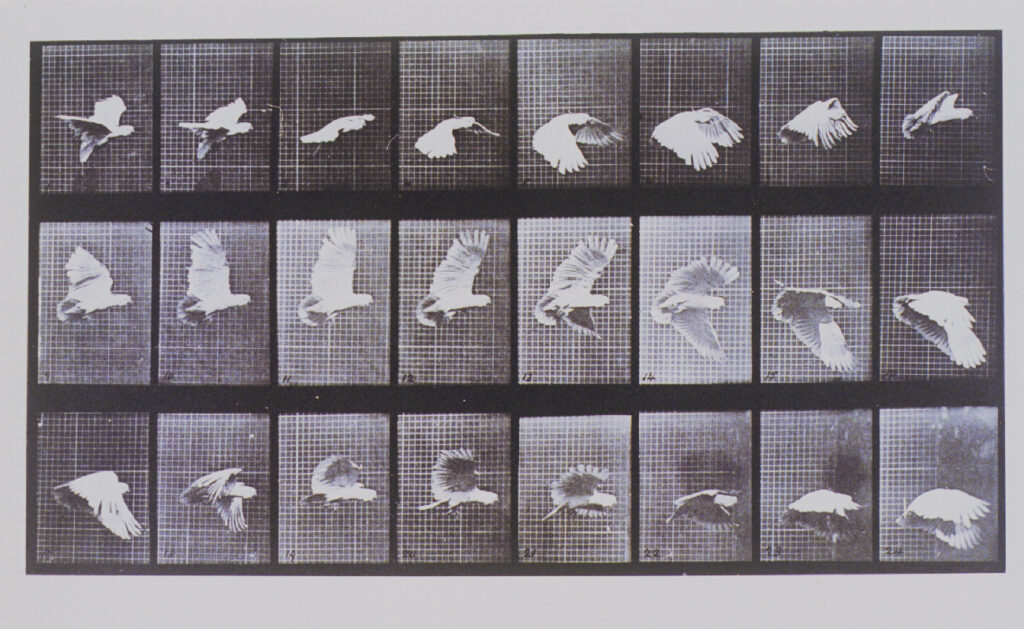

Muybridge’s stop motion photography – technological experiments conducted with an artistic flourish – would make him a leading figure in the history of photography.

With no state funding, Muybridge needed patrons for his work. The approval of the future Edward VII provided an important way into society and, after demonstrating his work at the International Exhibition of 1862, which took place on what would become the site of the Science Museum, he began taking out patents on his innovations.

Throughout the mid-late 1800s, Muybridge attracted audiences with projected sequential images of fencers, horses, and greyhounds (among others). This work later made him an inspiration to modernist artists, filmmakers, and musicians – from Andy Warhol to Philip Glass – interested in ideas of repetition and regularity.

Muybridge’s photographs became popular as sport modernised: rules were set down and matches were scheduled and promoted months in advance and played against the clock for the benefit of paying spectators. Like other modern mass participation sports – most famously association football – boxing was the product of an urbanising world. Gloves were mandated, equipment was standardised, the ‘Queensbury rules’ were introduced.

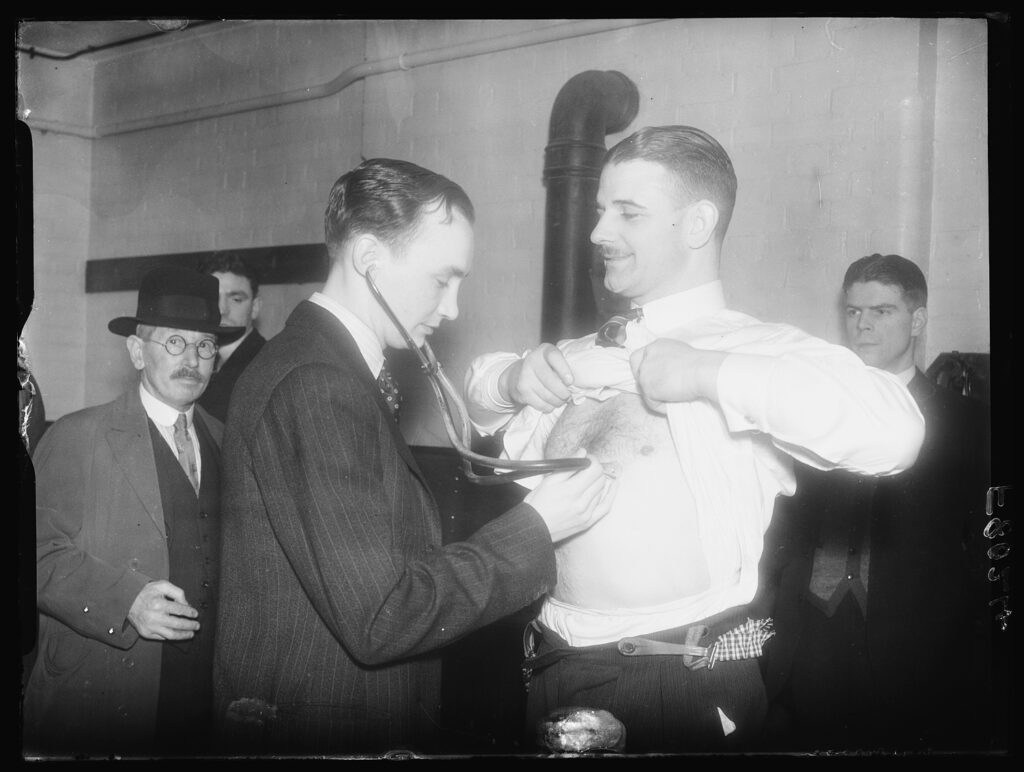

The Victorian practice of documenting sporting achievements, alongside the development of stricter rules and regular fixtures, also created the idea that ‘records’ were not just factual reports but benchmarks to be ‘broken’. Excellence was now determined by how fast athletes ran, how much weight they could lift, and how many bouts they could win in comparison with the towering figures of the past.

At a time when the experience of the industrial revolution was rapidly altering the ways in which people understood the world, Muybridge changed perceptions of time and space. The ‘sweet science’ of boxing would, like Muybridge’s photography, come to straddle art and science.

Boxing had been called a ‘science’ since the sixteenth century. It may be a working-class sport, but since the Restoration through to Turki Al-Sheikh in the present day, it has frequently depended on royal, aristocratic, and celebrity favour. Its appeal across the highest and lowest levels of society rested on the idea that there was great skill in ‘the science’ of not being hit.

Here it’s also worth saying that, a little confusingly, the term scientist as we commonly understand it now was not invented until centuries after boxing was first called a ‘science’. ‘Scientists,’ as we know them, were a child of the industrial revolution. They were sniffily regarded in comparison to wealthy gentleman ‘natural philosophers’. The transformation in ‘the science’ of boxing accompanied the rise of this new professional breed of ‘scientists’ in the nineteenth century.

Muybridge’s sequential photographs of boxers were not just part of this trend, they aided the development of a modern science of boxing. His photographs illustrated fractions of movement that the unaided eye could not see. There is a clear line from Muybridge’s masterful collection of photos Animal Locomotion (1887) to today’s world of video sports analysis.

Further measurement and close observation – of the kind Muybridge pioneered – has gradually led scientists to understand that a boxer’s punch power is primarily generated by their legs, then trunk rotation, and much less significantly by arm extension (it’s been estimated that only around 24% of a punch’s power comes from the arm). Boxing is not, and has never been, cavemen punching each other’s lights out. It is about squats, lunges, and lifts.

More recently, it’s been argued not just that boxing is a ‘science’ but that every bout represents a kind of live experiment to measure the boundaries of how much physical, psychological, and emotional stress a person can withstand. The psychologist Angela Patmore described sporting greatness as the ability to withstand the maximum degree of stress in the performance of a chosen skill. The irony is that while we are often told that sport is good for us, it tends to generate more serious injury and physical pain that ‘real life’.

What about art? The term ‘sweet science’ was coined by the writer Pierce Egan, whose classic works of Victorian sports writing seeped into the wider literary and cultural consciousness not only through the popularity of his books, but through its appropriation by writers such as the novelist Charles Dickens. Boxers, boxing terminology, and boxing metaphors feature across the entirety of Dickens work, from The Pickwick Papers to The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

During the nineteenth century, renewed interest in the classical world not only led to a resurgence of interest in Greek and Roman sculptures – such as the astonishing Quirinal Boxer – but initiated a trend of fighters serving as models for Royal Academicians. Throughout the twentieth century boxing and boxers continued to attract significant artists (such as Francis Bacon) while today there are now also boxers who have trained as artists (famously Joe Joyce).

Even more significant was the popularity of boxing at the dawn of film and broadcast media. Preindustrial sport victories were more likely to be absolute, but thanks to the sporting calendars introduced in the Victorian era, the idea of the rematch, and with it, stories about rivalries, revenge, and redemption proliferated. With self-improvement, determination and tenacity, astounding swings in an athlete’s public fortune became possible.

New media provided a platform for these stories that could lift individual boxers into the affection of millions. The infamous Dempsey-Tunney rematch of 1927, when a controversial ‘long count’ appeared to save Gene Tunney from defeat, encouraged a massive boom in radio sales.

Nowadays, the growth of digital media technologies, and with them global audiences, has meant that the path from successful boxer to celebrity and entrepreneur – first walked by figures such as ‘Gentleman’ John Jackson and Daniel Mendoza in the nineteen century –has enabled modern boxing stars, such as Tyson Fury and Anthony Joshua, to amass unthinkable fortunes.

Boxing’s popularity at the dawn of radio might also explain how the sport has worked its way so successfully into our everyday language: whether you are ‘out for the count’, or getting ready to ‘throw in the towel’ or ‘roll with the punches’ (to name three phrases of hundreds).

Similarly, inspired by Muybridge’s breakthroughs, if not pilfering his methods, Thomas Edison made boxing a focus of his early film periodicals. The drama, visual contrasts, and constraints of the ring played to the strengths (and technical limitations) of early film and newspaper photography.

Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight (1897), a bout between ‘Gentleman’ Jim Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons for the world championship in America, is often judged the world’s first edited, widescreen and feature-length film release.

This strong bond between the pioneering days of film and broadcast also helps explain why boxing has enjoyed such a resurgence through iPhone movies and social media influencers. Boxing provides explosive and unpredictable action, as well as real danger, in short attention-hogging bursts.

Boxing is a natural home for the showman, the entrepreneur, the innovator. It can retell compelling stories that are extremely familiar, but which retain enormous resonance and power: defeat in victory and victory in defeat. The contrast between the physically strong and the morally weak. Self-assurance tempted by ambition. The true boxer faces the fighter who must win at all costs. Control in the ring and chaos outside of it. Do you stand and fight, or do you take the fall?

It is a larger-than-life world that Muybridge would have understood. Not only was he an eccentric – and at times erratic – showman, lecturer, animator, entrepreneur, and inventor, but he was also a murderer. Muybridge shot his wife’s lover at point blank range in 1874 but, amazingly, was acquitted by a jury on the grounds that they would have done much the same thing.

Whether as part of the Riyadh Season or in a small hall, in white collar boxing or on YouTube, the popularity of boxing in this world of new digital technologies builds on Muybridge’s pioneering work. The industrial world created the sweet science.