Thinking of robots tends to conjure images of humanoid figures with metal exoskeletons or AI-powered machines with realistic human faces, reflecting the science-fiction fantasies which have captured public imagination for many years. However, throughout history there has been a consistent fascination with self-operating machines. In fact, people have been creating robotic and automaton animals for hundreds of years.

Coming from Ancient Greek, the word ‘automaton’ means ‘acting of one’s own will’. Powered by clockwork and other similar mechanisms, these mechanical creations paved the way for the robots we know today. The word ‘automaton’ was used to describe many early self-regulating machines, as the term ‘robot’ did not exist until the 20th century. The word ‘robot’ was first introduced in 1920, in the play Rossum’s Universal Robots written by Czech writer Karel Čapek. It stems from Slavonic origins, specifically the word ‘robota’, meaning ‘forced labour’.

One of the earliest known references to an automaton is from c. 400BC. Around this time, Archytas of Tarentum designed a steam-powered flying ’pigeon’, which was reported to have been able to fly up to around 200 meters. Animal-shaped automata have been used to demonstrate mechanical capabilities for centuries and were a point of interest for many inventors, including Leonardo da Vinci.

The Italian artist and inventor has been credited with creating at least one automaton lion in the 16th century as a gift for the King of France, Francois I. Some reports say he created a minimum of three lions, with at least one of these reported to be able to move its head and walk by itself. Our understanding of this invention is mainly built off eyewitness accounts and written descriptions of these creatures: the original lions no longer exist and Leonardo da Vinci left no detailed plans or sketches.

Using contemporary accounts, Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of mechanisms and additional supplementary archive information, the lion has been recreated multiple times. The above examples were displayed at the Italian Cultural Institute in Paris and Chateau du Clos Lucé, Leonardo’s home for the final years of his life.

Animatronic animals were also extremely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In particular, there was a large trend for animatronic birds in cages, like this example from 1900-1910, built by French company, Bontems. Due to the popularity of live songbirds as pets, their mechanical counterparts proved to be extremely successful.

The bird sits inside a brass cage and is powered using a winding mechanism. Once wound, a lever on the side of the base is used to operate the bird which moves its head and tail as well as opening and closing its beak while a clockwork music box in the base ‘sings’. This performance can also be set to occur at irregular intervals, enhancing the realism of the animal and its behaviour. Automaton birds created by Bontems were highly prized due to the quality of their creations and the accuracy of the songs the birds produced.

The automaton industry thrived in France, with many manufacturers based there. Another French creator of automaton animals was the company Roullet & Decamps who produced some more fantastical creations including this rabbit in a cabbage. Powered by a winding key, the rabbit would rise out of the cabbage, wiggle its ears, open and close its mouth and look around before returning to its original position.

Roullet & Decamps’ other creations included a jumping tiger, a violin playing rabbit and a smoking monkey. The whimsical behaviours of these animals won over much of the general public and were key to the broad social acceptance of automaton animals. These fanciful creations paved the way for the robotic toys and pets popular today.

From the middle of the 20th century, automata and robots inspired by animals moved from at-home curiosities to scientific endeavours.

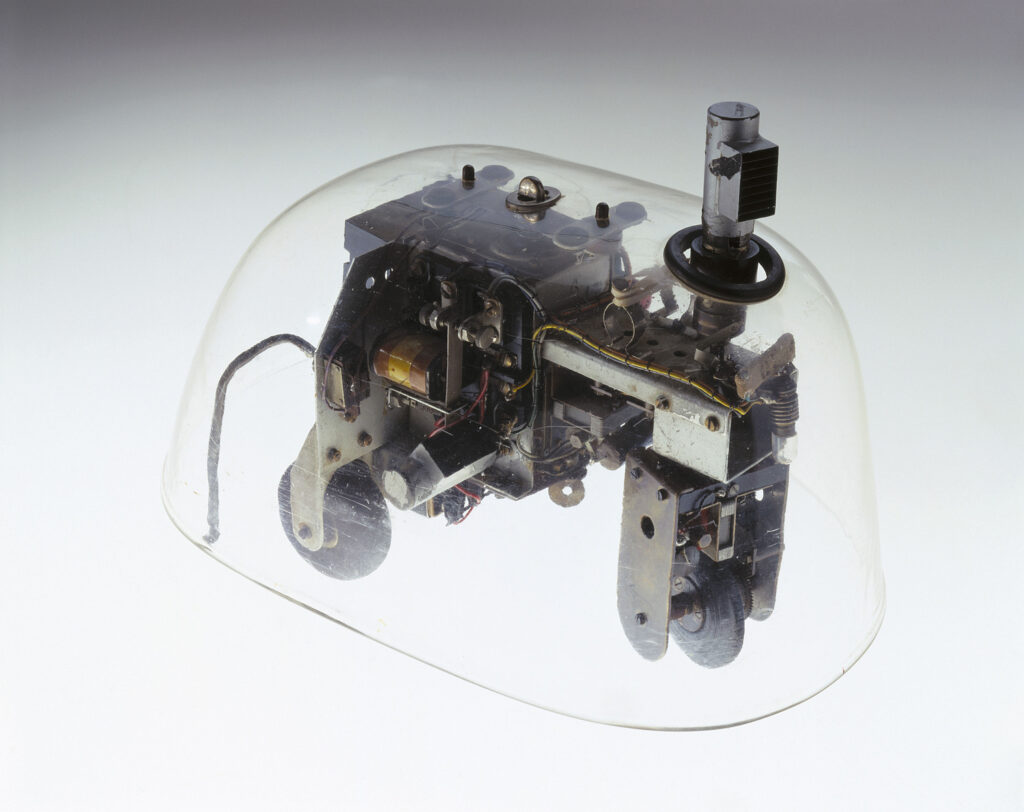

Some of the first autonomous robots demonstrated animal characteristics. William Grey Walter, a neurophysiologist, created two ‘tortoises’, Elmer and Elsie, in 1948-1949 in his efforts to understand how the brain functions.

Through the use of artificial neural networks these robots were able to respond to and move towards light and avoid obstacles in their way. Additionally, when Elsie’s battery was low, she was able to guide herself back to her charging station.

They were given the name ‘tortoises’ due to their appearance and slow movements. Elmer and Elsie can be seen as the first modern robots in the way we understand them today. They demonstrate a huge technological advancement and were even featured at the Festival of Britain in 1951.

Developments in robotics continue to be inspired by the behaviour and design of animals, with many modern robots designed to mimic their movements, known as biomimicry. Animal-inspired capabilities enable robots to explore and enter terrain and spaces not viable for humans, assisting with activities such as search and rescue operations or manufacturing.

The creation of cybernetic structures based around the physiology of humans and other creatures also plays a significant role in scientific research. For example, the winged robot, DASH, was used in practical experiments to evidence the theory that flight evolved from tree-dwelling, gliding, birds instead of those which took off from the ground.

The 90s and 2000s featured a real boom of robotic and virtual toys including robot dogs, the Furby, and even robotic dinosaurs! One of the most prolific examples of this is the Tamagotchi. First released in 1996, this virtual toy was a phenomenon with over 82 million units sold since.

Through simple graphics and non-pausable gameplay, this toy evoked a sense of love, care and responsibility among many players. Some players even buried their Tamagotchis when they died instead of resetting them!

At the time, the Tamagotchi was one of the first video games to be marketed primarily to girls, likely playing into stereotypes with the strong focus on nurturing and caring. Although this toy sits more within the virtual realm, rather than robotic, it illustrates the deep emotional connections capable of being formed between people and non-living animals. The Tamagotchi continued the trajectory begun with automaton and robotic toys, blurring the lines of reality and providing a creature which can be played with and cared for without the responsibility, and expense, of a real-life pet.

This opened the doors for further developments in the robotic toy pet market into the early 2000s. While some of these toys, such as Furbies, have stood the test of time and are still around, with some contemporary modifications, manufacturers have continued to capitalise on this trend and modernise robotic toys.

In 2016, Fisher Price released Smart Toy Bear, a cuddly bear which listens to and interacts with its owner. It uses voice recognition and machine learning to figure out what activities the child likes and remember what they say. However, it raised concerns around hacking and the easy availability of the children’s data. In this case, the app which connected to the toy was the weak point for hackers, an issue discovered by a Boston-based security company. Fisher Price released a statement upon remediation of the issue and believed that no data had been taken and distributed. Nevertheless, it illustrates some of the new challenges that surround smart toys – ones that were never an issue with the automaton animals of the past.

As well as being used as toys, robotic pets have also been proven to have a medical benefit. Robot dogs and cats, such as these created by the company Joy for All, have begun to be used to combat loneliness in elderly patients. They are proven to be especially beneficial for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: decreasing levels of stress and anxiety as well as the use of related medication.

Pet therapy is successful among such patients, and the use of robotic pets reduces the issues associated with the involvement and care of living creatures. The bonds created between humans and robotic pets likely ties into human tendencies to anthropomorphise – attributing human qualities to machines, like they do for pets, which furthers the emotional bond.

Humans have an innate instinct to nurture and care for animals and this does not only extend to living creatures, but mechanical and virtual ones too. Robotic and automaton animals have been a source of fascination throughout much of human history, either through a desire to replicate the natural world, demonstrate technological advancements, create a spectacle or to provide an output for people’s natural capacity to nurture. Robotic, automaton and even virtual animals are becoming increasingly prevalent and it is likely that they will remain part of society for many more years to come.