As we begin, from a safe distance, to collect objects which represent COVID-19, it’s worth remembering that collecting objects related to pandemics (or epidemics) is nothing new.

Within the vast and varied Science Museum Group Collection (and in Sir Henry Wellcome’s Museum Collection which we also care for on behalf of the Wellcome Trust), there are many remarkable items which tell stories of past pandemics.

Many items were collected long after the events they memorialise. Only in the last generation or two have curators caring for the everyday items of the past begun to turn their trained eyes onto the present.

Collecting items related to pandemics is difficult. Items rarely survive, either due to their ephemeral nature (such as rapidly changing advice given on posters), because they are destroyed (due to contact with pathogens or bodily fluids) or perhaps because the people living through these traumatic events were eager to forget.

While our curators continue identify which items to collect to represent our experiences of the coronavirus for future generations to explore and study (such as homemade masks), here are ten remarkable items from previous epidemics.

BUST OF HIPPOCRATES

Over the centuries, the ancient Greek doctor Hippocrates (born c.460 BCE) became a talisman of the environmental approach to medicine, one that looked to how a person’s individual balance of health and sickness could be affected by ‘airs, waters and places’.

Hippocrates and his followers developed the idea of the ‘epidemic constitution’ to explain patterns of disease, namely the influences of the weather, soil, water (marshes, lakes, rivers), and even of the stars on the prevalence of particular diseases at specific times.

SAINT ROCK

The Black Death, the most famous Mediaeval pandemic, swept through Asia and Europe in the mid-fourteenth century, killing up to 200 million people.

According to his story, Saint Rock, a native of Montpellier, encountered the plague whilst on pilgrimage to Rome. He used his God-given powers to heal sufferers; but when he himself succumbed, a dog licking his sores saved him.

The dog, which is often shown in representations like this one, became the emblem by which he was recognisable.

People could pray to Rock as patron saint of plague sufferers in the later epidemics that affected the world up to the 1800s.

CHOLERA SNUFF BOXES

Health workers have been rightly revered in this current pandemic, with their efforts acknowledged with weekly public applause.

In earlier epidemics a similar devotion to caring was also recognised – sometimes in unusual ways. This silver snuff box was presented to Matthew Whitehill to honour his actions during a major epidemic of cholera.

Another box is inscribed to a surgeon, Robert Fortescue “…for his humane and unceasing attention to the Poor during the awful visitation of malignant cholera at Plymouth…”.

Deadly diseases were a constant threat to UK citizens in the 1800s, and the waves of epidemic cholera that visited these islands terrified the public.

MODEL BUILDING VENTILATOR

Social distancing has been one of the golden rules of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the risk of infection lower in the open air than in buildings or confined spaces. Victorian health champions also had ideas about how to minimise infection.

A sanitary engineer named Robert Boyle believed in the power of ventilation to clear disease-causing miasmas or germs from public buildings, and he took models like this to public health exhibitions to sell his idea.

If air is blown through the model the balls of cotton wool – representing stagnant air – will rise, showing natural convection at work.

Across Britain, Victorian public buildings survive with the characteristic ‘chimneys’ and ground floor level air intakes of the Boyle system.

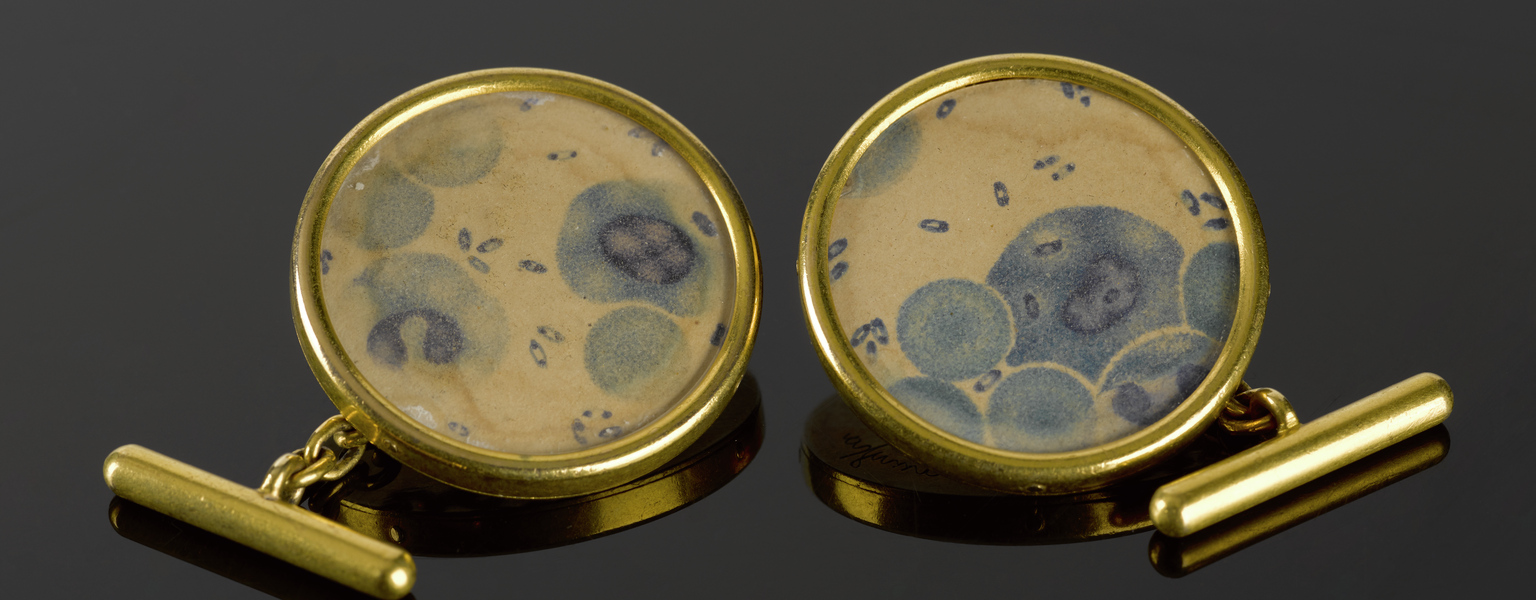

PLAGUE CUFFLINKS

The bacterium which causes plague, the infectious disease responsible for the Black Death, were discovered in 1894. These cufflinks contain pictures of two different strains of these bacteria, with their names engraved on the back.

It is believed that Fabergé, the celebrated Russian jeweller, made these cufflinks. The use of images of bacteria for the cufflinks suggests the pride taken in the study of bacteria.

Dr Wise on Influenza

Public communication has been a prominent feature of the current pandemic.

A century ago, the viral pandemic of ‘Spanish’ influenza led to what is probably the first state-sponsored health propaganda film, Dr Wise on Influenza (1919).

Not exactly a snappy infomercial (it runs for 18 minutes), this is the story of Mr Brown who ignores his bout of ‘Spanish’ Flu and infects several of the fellow clerks in his office.

It is chilling a hundred years later to see the film advise the viewers to isolate at home and to make a facemask.

Fortunately for us, this piece of recent history was collected by the British Film Institute when it started its archive less than 20 years after the event. We include it here in the spirit of #CollectionsUnited.

POLIO TEACHING DOLL

Alongside the officially sanctioned, mass-produced, and hi-tech objects created in response to epidemics, we also collect the homemade, the improvised and the one-offs for the collection.

This child’s ceramic doll, encased in a body-length plaster cast, was used by nursing staff to explain to young polio patients and their carers the treatment they’d be receiving.

Before there was a polio vaccine, one disputed therapy involved encasing young patients in plaster casts – often for long periods. This was intended to rest and avoid tightening of the muscles affected by the virus.

CARD SORTER CARDS

Although the gathering of statistics on causes of death became normal practice in the 1800s, epidemiology has really come into its own as a sophisticated mathematical discipline since the Second World War.

A practice that began in the study of infectious diseases cut its technical teeth on non-infectious conditions such as cancer and heart disease, and notably with the famous studies on smoking and lung cancer.

Before computers were widespread, people studying patterns of illness could punch the details into cards like these and use a machine to sort them into different categories to identify links between lifestyle and disease.

BIFURCATED NEEDLE

In 1796 Edward Jenner used a small sharp-pointed instrument, known as a lancet, to administer the world’s first vaccine.

In a risky experiment, Jenner then demonstrated that the child he vaccinated (James Phipps) was immune from the deadly disease smallpox.

Nearly two centuries later smallpox became the first human infectious disease to be eradicated. Vaccination was central to this global success and was largely delivered via another small, sharp-pointed instrument – the bifurcated needle.

Ingeniously simple, it held a single-dose drop of vaccine between the tiny prongs which were then pricked into the skin of the upper arm. At the height of the eradication campaign over 200 million vaccine doses a year were given in this way.

HIV/AIDS: AWARENESS LEAFLET

In April 2020 a letter was delivered to every household in the UK. It outlined guidance to be followed and the measures being taken by government to combat the coronavirus. We’ll be adding the letter to our collection as part of our COVID-19 collecting project.

Such mass messaging is not unprecedented.

In 1987, a different virus was global news. HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS, the life-threatening condition that could result from it, had first been reported earlier that decade.

The leaflet was part of a campaign to raise awareness and dispel confusion around how the virus was spread. Millions were delivered, but few appear to have survived. The leaflet displayed in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries was fortuitously found in a curator’s garden shed.

Personal Protective Equipment

Some epidemic diseases are so dangerous that health workers don several layers of protective clothing before entering infected areas.

This personal protective equipment (PPE) was used during a major outbreak of Ebola in Sierra Leone in 2014-15.

Worn in high humidity and temperatures up to 40C, at the end of each shift such items were either disinfected for re-use or discarded.

Fortunately, the Science Museum Group was able to collect some examples which would usually be routinely destroyed. A full set of PPE is displayed in our Medicine and Communities gallery at the Science Museum.

The Science Museum Group is collecting objects and ephemera to document the COVID-19 epidemic for future generations.

When the Science Museum re-opens on 19 August 2020, you can explore more about public health and our response to previous epidemics in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries.