As the Library and Archives Conservator for the Science Museum Group my work can be quite varied.

One day I can be advising on display conditions for objects being loaned for display, and the next, researching nitrile gloves or washing an engraving to remove soluble discolouration.

Conservators therefore have and need a wide range of skills.

What I wasn’t expecting to learn one cold day in February, was a potentially nefarious skill.

Beata Bradford, Archive Collections Manager at the National Collections Centre, logged a request for help from the conservation team to open a locked book.

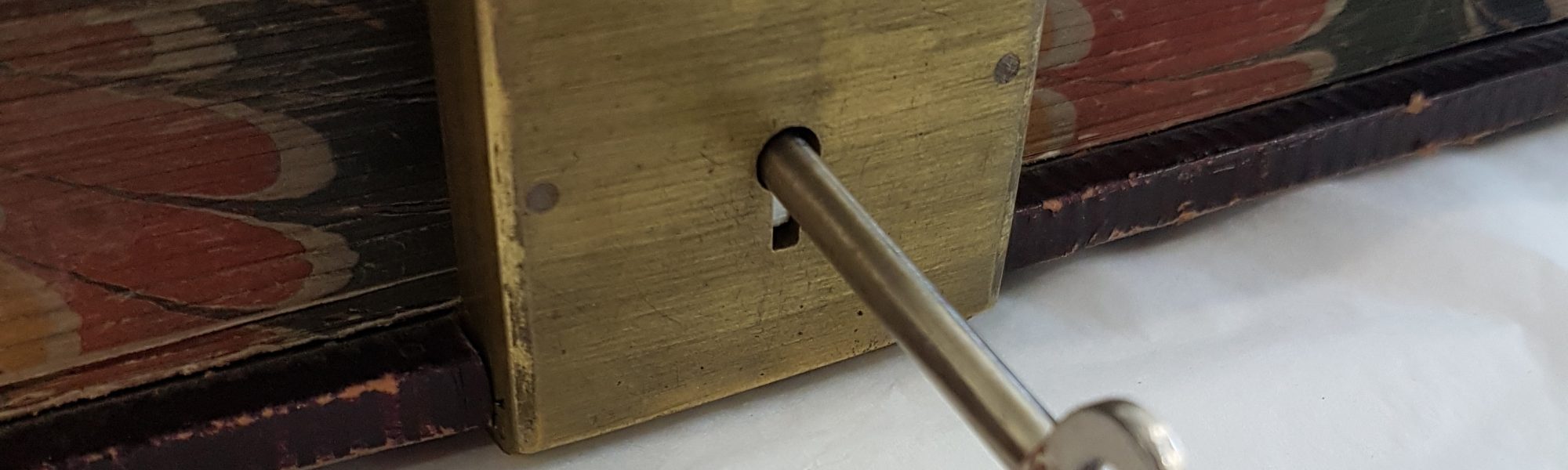

The leather-bound book was used for recording minutes. It has a marbled fore-edge and came with a key but couldn’t be unlocked.

Beata informed me that the key had been made by a locksmith at the Science Museum and she thought the book was last opened in the mid 1990’s.

The first step was to try to use the key. It wouldn’t turn as it caught on the sides of the keyhole.

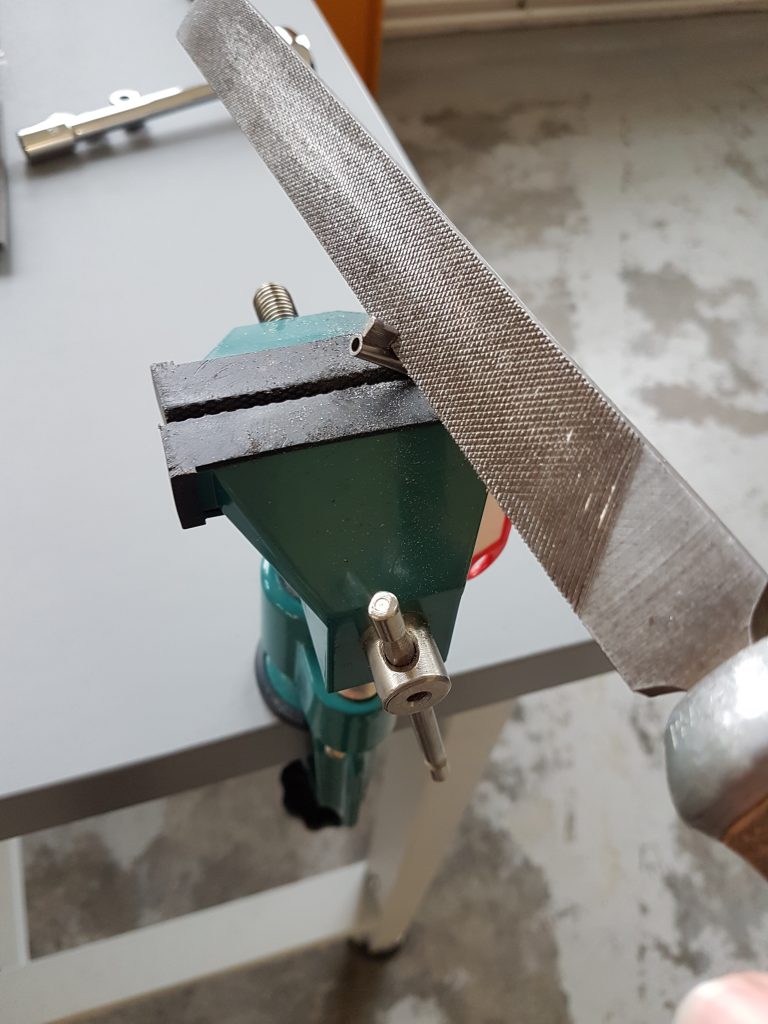

As the key was not original, I attempted to file it down using a trusty file and vice to see if it could turn freely in the lock.

However, while the key did turn (catching one of the locking mechanisms), the lock would not open.

It isn’t every day that you get to legitimately hone nefarious skills to help with a conservation treatment.

I embraced the opportunity and read various articles and looked up videos on lock picking.

Fortunately, I came into work with bobby pins in my hair and these along with a range of other tools were used to attempt to pick the lock.

Still it wouldn’t open.

I then sourced and bought a lock picking kit online. While waiting for this to be delivered I couldn’t help but wonder what was inside the book.

Finally, the kit arrived and having mastered the art of picking a lock in under a minute, I tried with the books’ lock.

It refused to budge.

My days as a lock picker were over, or so I thought. The only option left was to consider destructive methods.

I sought the advice of Objects Conservator Simon Stephens and while we did contemplate requesting the services of a locksmith, we were fairly certain that the locking mechanism had broken (and also the cost of a locksmith exceeded the value of the book).

With Simon’s help we evaluated the lock and determined an approach which would aim to minimise any visible damage to the book and the lock itself. We decided to cut through the two metal catches of the locking mechanism.

With the book angled, the keyhole plate and the side plate opened up slightly, providing access, we could see where the two metal catches locked in.

Using the slimmest Dremel tool we could find we were able to go between the plates and cut into the two metal clasps.

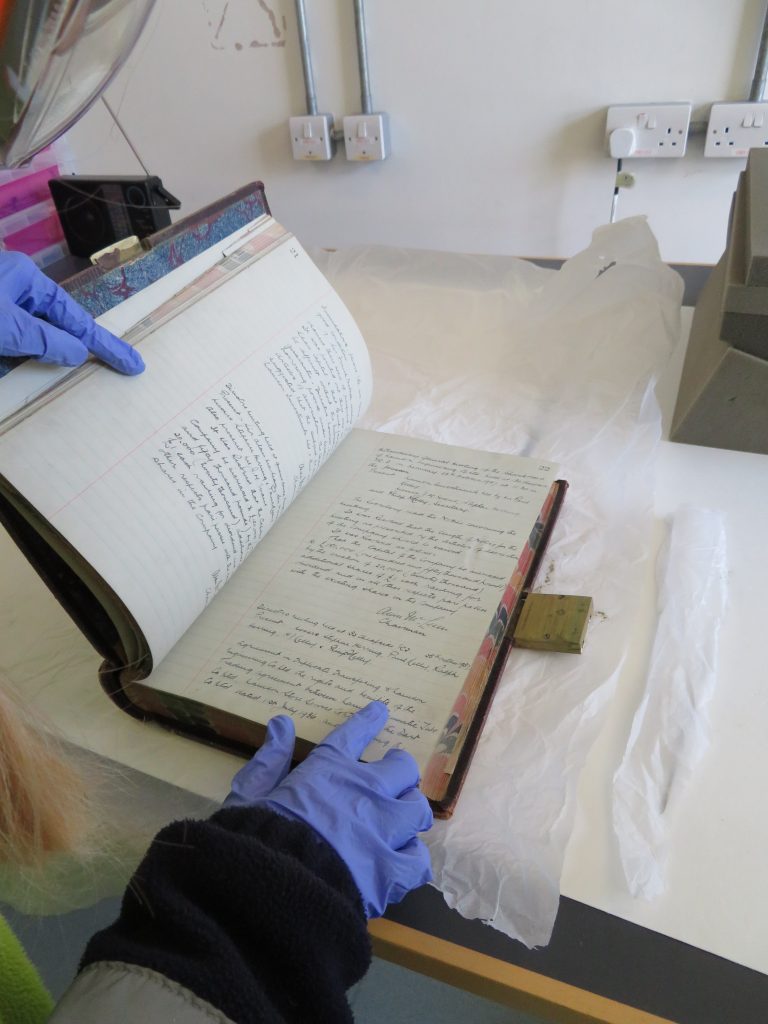

Finally the book was open!

We excitedly turned some of the pages to see what was inside and to our surprise the book looked blank. We couldn’t believe it.

Luckily, this was just the first section and we soon found that the book was full of handwritten notes and minutes.

With the locking mechanism open, we could access the back of the keyhole plate and remove this to access the internal mechanism.

We discovered that the locking mechanism was indeed broken, so perhaps I will continue honing my new skill—for future work purposes only!

The cut clasps were removed, and the locking mechanism documented and put back together and left unlocked for the future.

For those who are curious, the book was ‘Lamson Engineering Co Ltd, minute book, directors’ meetings 1937–1949’.

Lamson companies were the principal suppliers of cash railways (equipment for expediting financial transaction in shops) and pneumatic dispatch tubes for cash handling.

Between 1890 and 1970, you might have encountered the cash railways almost anywhere in the UK. After 1960 they rapidly disappeared, becoming increasingly rare by 1980.

During that time, shoppers were fascinated to see their payment for goods being placed in a small wooden carrier which was then clipped to an overhead trolley and shot by catapult along a taut wire to a raised cashiers’ desk.

A minute or so later, their change and receipt would be returned the same way.

In the Science Museum Group Collection we have parts of both the Lamson cash railway and the pneumatic tube system which you can see below.

Follow more of our conservation-related exploits on Twitter or keep an eye on this blog as we share more of our behind the scenes work with you.