Representatives from nearly 200 countries agreed at the COP28 climate summit today to begin reducing the global consumption of fossil fuels to avert the worst of climate change, such as flooding, fatal heatwaves and irreversible changes to ecosystems.

In Dubai at COP28, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention (COP), there has been an urgent effort to keep the planetary warming threshold of 1.5 degrees in reach, the goal outlined in the 2015 Paris agreement.

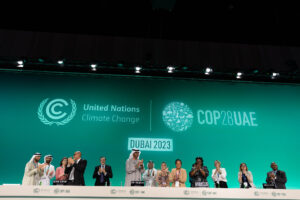

Within minutes of opening Wednesday’s session, COP28 President Sultan al-Jaber gavelled his approval of the central document — the global stocktake that says how off-track the world is on climate, and how to move towards global net zero by 2050.

The deal came after two weeks of gruelling negotiations which went into overtime after many nations criticised a draft text released on Monday for failing to call for a ‘phase-out’ of oil, gas and coal.

More than 100 countries had lobbied hard for language in the COP28 agreement to ‘phase out’ fossil fuel use, but met opposition from the Saudi Arabia-led oil producer group OPEC, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Today’s agreed deal calls for ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner … so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.’

It also calls for a tripling of renewable energy capacity globally by 2030, speeding up efforts to reduce coal use, and accelerating technologies such as carbon capture and storage that can clean up hard-to-decarbonize industries.

For optimists, this first of its kind deal signals beginning of the end of the age of fossil fuels. ‘It is the first time that the world unites around such a clear text on the need to transition away from fossil fuels,’ said Norway’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Espen Barth Eide. ‘It has been the elephant in the room.’

Danish Minister for Climate and Energy Dan Jorgensen put the deal in context: ‘We’re standing here in an oil country, surrounded by oil countries, and we made the decision saying let’s move away from oil and gas.’

However, for pessimists, it is striking how little progress has been made over the past 28 COP meetings. Having attended the Toronto Conference on the Changing Atmosphere in 1988, where the substance of the discussions differed little from today, it is difficult to disagree.

Prof Myles Allen at the University of Oxford, and Director of Oxford Net Zero, commented that though many will be relieved the text prioritises ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’ they may be worried that it talks of ‘abatement and removal technologies such as carbon capture and utilisation and storage, CCS.’

The 1.5°C scenarios indicate around 10-30% of current usage at the date of net zero: coal almost phased out, and roughly half current oil and gas consumption, all compensated for, or ‘fully abated’, with CCS at source or carbon dioxide recapture from the atmosphere.

‘That is a vast and global carbon dioxide disposal industry, 100 to 300 times larger than the 40 million tons of carbon dioxide that we currently dispose of every year,’ said Prof Allen. ‘So, we need to scale up CCS by at least two orders of magnitude – far more, in percentage terms, than we need to scale up many other low-carbon technologies.’

COP28 President Sultan Al Jaber called the deal ‘historic’ but added that its true success would be in its implementation: ‘We are what we do, not what we say,’ he told the crowded plenary.

There is a lot left to do: the International Energy Agency on Sunday released an assessment showing that non-binding pledges by 130 governments along with 50 fossil fuel companies so far at COP28 would fall far short of what is required.

The pledges – tripling renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency by 2030, and sharply reducing emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane by energy companies – would cut energy-related greenhouse gas emissions by only 30 percent of what is needed by 2030, the IEA said.

‘The world is going to need to remain focussed on emissions reductions for a long time to come if we are to stabilise the climate,’ commented Prof Stephen Belcher, Chief of Science and Technology of the Met Office, and Science Museum Group Trustee, coauthor of a study in the journal Nature that calls for greater precision in defining the Paris 1.5 degree target (as the paper points out: ‘the Paris statement contains no formally agreed way of defining the present level of global warming. The pact does not even define ‘temperature increase’ explicitly and unambiguously.’)

Prof Richard Betts, Chair in Climate Impacts, University of Exeter and Met Office Hadley Centre, commented: ‘It’s worrying that the Dubai negotiations went ahead on the basis of a misunderstanding of how close we are now to reaching 1.5°C global warming. The text gives observed warming as ‘about 1.1°C’, but this is already out of date – the actual current global warming level is about 1.3°C. While this is clearly not the main reason why the agreement falls short of what is needed, it may have contributed to a reduced sense of urgency.’

Significantly, at the start of the summit, 134 countries signed a declaration pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions related to producing and consuming food, underlining the importance of reforming the global food system, which accounts for around a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate change has also placed the world in danger of breaching numerous planetary ‘tipping points’, according to an assessment compiled by more than 200 researchers that was released at COP28.

‘Harmful tipping points in the natural world pose some of the gravest threats faced by humanity. Their triggering will severely damage our planet’s life-support systems and threaten the stability of our societies.’

Last week, in the journal Science, a major review of ancient atmospheric carbon-dioxide levels suggests that the last time atmospheric carbon dioxide consistently reached today’s human-driven levels was 14 million years ago—much longer ago than some existing assessments indicate.