In 2018 the Science Museum embarked on a collaboration project with Google Arts & Culture to support our work to increase public access to the collection by expanding our digital records of objects.

Five years down the line and it has resulted in the digitisation of around 9,000 pieces of 2D material including prints, drawings, as well as coins and medals. All of which are available to freely explore on the Science Museum’s Google Arts & Culture homepage alongside a selection of curated digital exhibitions, covering topics such as robots, alchemy and coins.

Below, we have selected eight unusual objects from the digitisation project, exploring the breadth of stories which can be discovered through this material from the comfort of your own home.

Gold medal commemorating the recovery of Queen Elizabeth I from smallpox, 1572

This medal celebrates the recovery of Queen Elizabeth I from smallpox. She contracted the illness in October 1562 and caused quite the commotion among the court as she had no direct successor and, with no cure available, there was a not insignificant chance she might die from the disease.

The contraction of smallpox is also likely to have contributed to Queen Elizabeth’s iconic image of a very pale face. A pale appearance was a status symbol at the time but is believed that Elizabeth I heavily indulged in the use of such heavy white lead makeup to conceal the effects of ageing as well as smallpox scars which marked her face.

Silver medal, appears to commemorate a comet or a shooting star in 1618, at Frankfurt-on-Main, German, 1618

This medal commemorates a comet seen on 19 November 1618 at Frankfurt-on-Main in Germany. This was one of three rare ‘great comets’ seen that year, specially named due to exceptional brightness that makes it visible to the naked eye.

Whilst this event was seen as a bad omen by the public, it provided astronomers and other scientists an opportunity to observe a comet with a telescope for the first time. The earliest known telescope dates to 1608, and the last recorded ‘great comet’ prior to 1618 was in 1577.

The comet was visible for more than seven weeks – even in daytime! It allowed the scientific community plenty of time to research the phenomenon, meanwhile King James I wrote a poem about it.

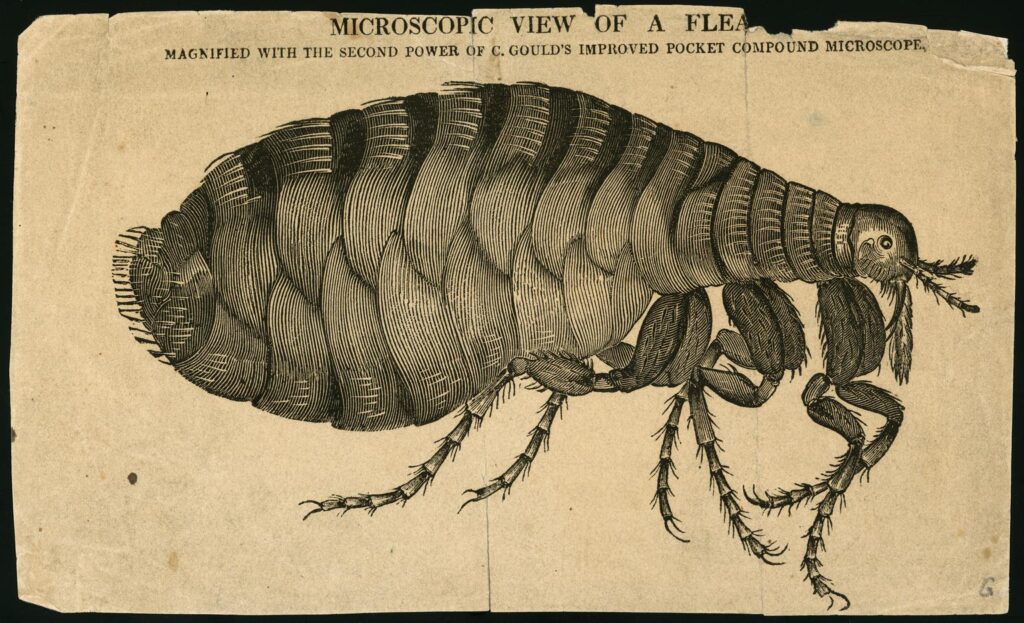

Microscopic View of a Flea, Unattributed (maker), 1825-1839

This trade card features a detailed engraving of a flea and was used to advertise the ability of the ‘improved pocket compound microscope’ developed by Charles Gould. It demonstrates the detail which could be identified through use of such equipment.

Fleas were a common subject of microscopic drawings, with the most notable created by Robert Hooke in his 17th century work, Micrographia. It was a seminal piece in the relationship between art and science, containing illustrations of life through a microscope.

Exterior of the Crystal Palace, from Kensington Gardens

This lithograph illustrates ‘The Crystal Palace’. The building was designed by Sir Joseph Paxton to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. Standing at 33 metres high the building housed around 14,000 exhibitors during the 5-month long show and even contained a 27ft tall glass fountain. The displays included a variety of scientific inventions including a printing machine, steam locomotives and Stevenson’s hydraulic press.

This illustration shows the building in its original home of Hyde Park. However, after the exhibition closed, the building was taken down and reconstructed in Sydenham Hill. Its new location was subsequently named Crystal Palace and it stood there for another 80 years before burning down in 1936.

Palladium Hydrogenium

Thomas Graham was a Glaswegian chemist and professor who became Master of the Mint in 1855, where he cast this coin in 1866 along with others which he circulated amongst friends. This coin was given to Sir John Frederick William Herschel, previous Master of the Mint, a fellow scientist, and son of Sir William Herschel – the discoverer of Uranus.

The coin is a manifestation of Graham’s discovery that hydrogen readily penetrated the crystal lattices of certain metals, a process he called ‘occlusion’. Iron, platinum and especially palladium are affected. He supposed that hydrogen gas was the vapour of a very volatile metal, hydrogenium, which formed an alloy with palladium. This coin was struck with this supposed alloy, which contains 147 u or 900 volumes of hydrogen.

Thomas Graham made a number of other scientific contributions such as in the process of dialysis and the diffusion of gases, with ‘Graham’s law’ named after him. His life and work is commemorated with another coin.

Medal commemorating the Polar explorers Nansen and Andree

This medal marked two individual polar expeditions that reached the North Pole in the 1890s. One was undertaken by Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who planned to reach the North Pole by harnessing the natural current of the Arctic Ocean. The expedition lasted 3 years. The medal is inscribed with the date the expedition began – 24 June 1893 – as well as Nansen’s likeness in front of the ship that carried him and his crew, the Fram.

The second expedition was a failed Arctic balloon expedition of 1897 from Sweden over the North Pole to Russia or Canada, which sadly saw all three Swedish crew members pass away: S. A. Andrée, Knut Frænkel, and Nils Strindberg. The medal is inscribed with S. A. Andree’s profile, the hot air balloon and a map showing the North Pole.

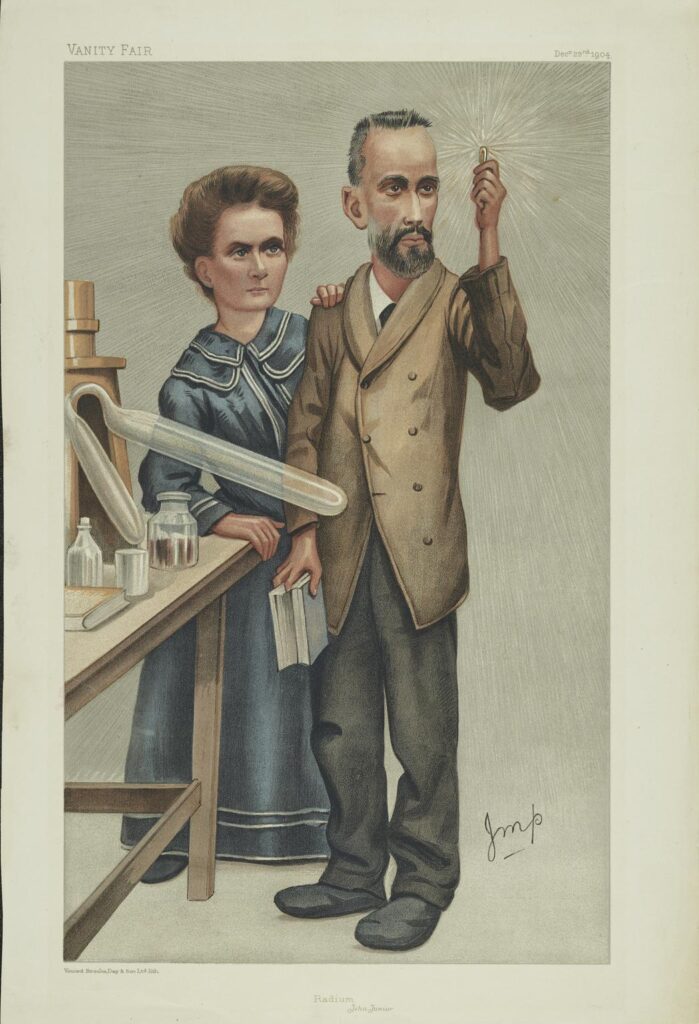

Chromolithograph Portrait. “Radium” [Marie and Pierre Curie] by IMP.

This print shows Marie and Pierre Curie holding up a piece of glowing radium in front of their scientific apparatus. It was painted by Julius Mendes Price, a war correspondent and artist and printed in Vanity Fair in 1904.

Radium was a new element discovered by Marie and Pierre in 1898. Somewhat controversially, Pierre is at the forefront of the image holding the sample, the principal actor, whilst Marie is depicted with a gentle hand on his shoulder – presenting her in a stereotypical gender role as a supporting wife. However, Marie was the one who had isolated the substance, gaining a Nobel prize in acknowledgement of this (along with her discovery of another radioactive element – polonium) in 1911.

Marie was the first woman to receive a Nobel prize, the first person to win two Nobel prizes and the first person to receive Nobel prizes in two different fields. Additionally, Marie and Pierre were the first married couple to co-win a Nobel prize in 1903, “in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel.”

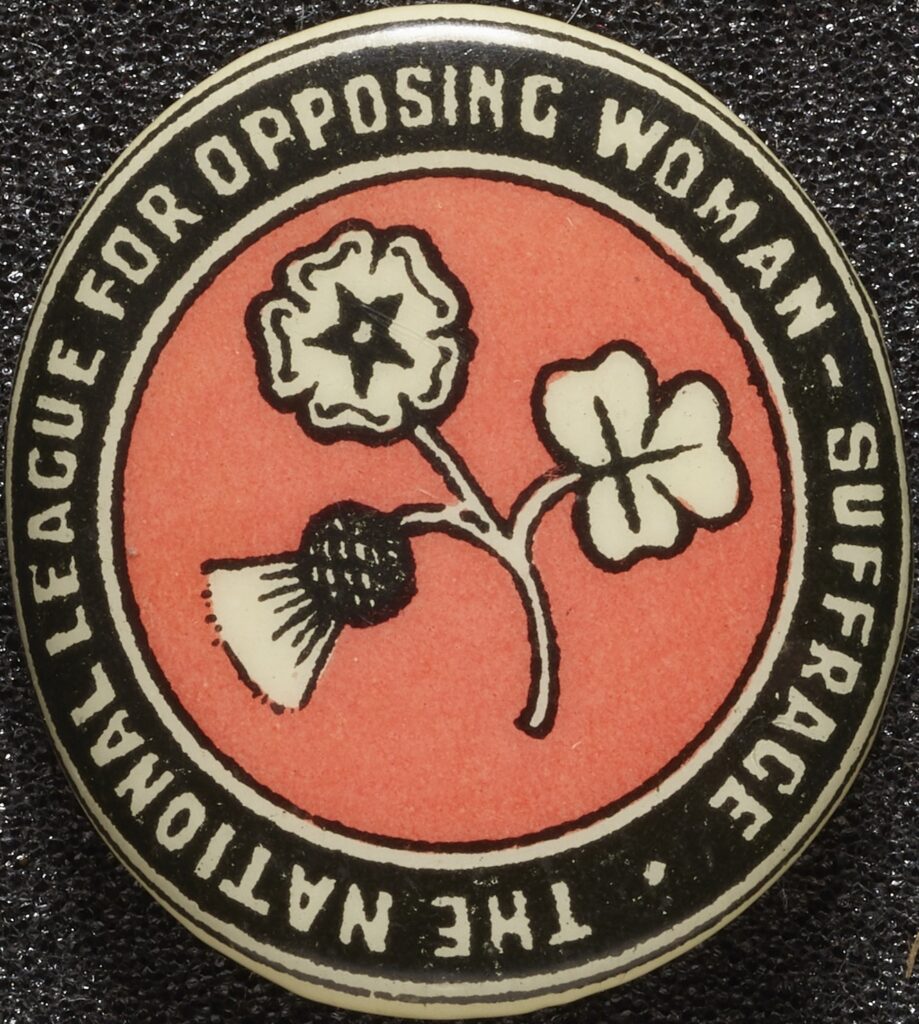

Lapel Badge, The National League for Opposing Woman-Suffrage, 1906-1928

This lapel badge illustrates an individual’s support for The National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage (NLOWS) which was formed in 1910 upon the merging of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League and the Men’s League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage.

While a lot of attention is rightly focused on the victorious suffragette and suffragist movements, there were also active counter movements concerned about how improved opportunities for women would impact on families, personal happiness and Britain as a whole.

This badge illustrates the presence of significant concern surrounding these shifting gender roles. By 1914 the NLOWS had 42,000 paying members and had collected over half a million signatures for petitions against votes for women.

The league’s campaign was unsuccessful and they disbanded in 1918. However, this lapel badge serves to illustrate the social and political ideologies and concerns which the suffragettes had to counter in their fight to win votes for women.

You can look at more of the objects digitised in the project and view the objects sorted by popularity, in a timeline and even organised by colour. The collection of images is also organised by category and theme, with varied categories such as extreme sport, railway, invention, and humour.