On the 135th anniversary of his birth, we’re celebrating the life and career of Edwin Hubble. The astronomer’s journey to evidence an expanding universe took him from an athlete’s childhood in Missouri, to law studies at Oxford, all the way to an observatory in California. Hubble’s voyage ends in the sky, where the NASA telescope that bears his name orbits the earth once every 95 minutes.

Edwin Hubble was born in 1889 in Marshfield, Missouri, and spent his childhood dividing his time between athletic pursuits and science fiction novels. He always had a fascination with the stars, going on to study mathematics and astronomy as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago in the hopes of becoming a scientist.

Despite his fascination with stars, but, in accordance with his father’s wishes, Hubble spent three years studying law at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. Returning to America after his father’s death in 1913, Hubble taught at a high school in Indiana for a year before he resolved to pursue astronomy. He returned to the Yerkes Observatory at the University of Chicago for a Ph.D. in astronomy, completing “Photographic Investigations of Faint Nebulae” in 1920.

Facilitated by his postgraduate studies, Hubble followed the stars to California. In 1919, he took up a position at the Mount Wilson Observatory and began working with the Hooker Telescope, which would maintain its position as the largest telescope in the world for the next thirty years.

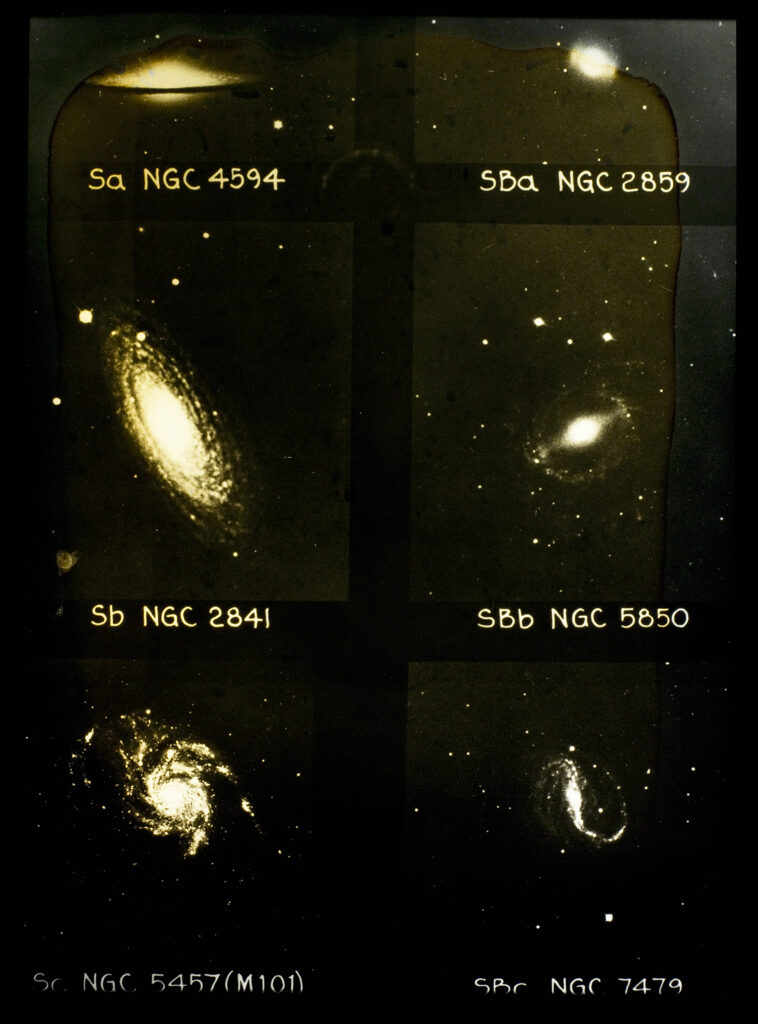

On the night of 5 October 1923, Edwin Hubble peered through the 2.5-meter Hooker Telescope at, what was then known as, the Andromeda nebula – a giant cloud of dust and gas. That evening, Hubble recorded the first Cepheid variable star in the Andromeda nebula; it confirmed Andromeda’s status as a galaxy.

The data he recorded was evidence that the Milky Way was not the only galaxy in the universe—and suggested that there were many, many more. Hubble had found proof, once and for all, that we were not alone.

In 1929, Hubble published his seminal paper, “A Relation between Distance and Radial Velocity among Extra-Galactic Nebulae”. The paper revolutionised the way astronomers understood the universe, and confirmed that the universe was constantly expanding. It also cemented Hubble’s place as a preeminent scientist.

Hubble’s paper examined the relative distance between galaxies by analysing their redshifts. A redshift is a metric by which astronomers can measure the relative intensity of photon energy: galaxies that show up on the redder end of the spectrum are located farther away than ones that show up blue.

By analysing the relative intensities of various galaxies’ redshifts, Hubble derived a principle now known as Hubble’s Law: that galaxies farther away from each other are moving apart at a faster rate than galaxies close to each other. This discovery compromised the notion of the universe is static, and laid the groundwork for accurate calculations of the age of the universe. Two years later, George Lemaitre put forth the possibility of a big bang.

What technology did Hubble use to measure these redshifts? Contrary to popular belief, Hubble never used the telescope names after himself—he died in 1953, nearly forty years before the telescope entered low earth orbit. Instead, Hubble’s work was conducted using the Hooker Telescope.

The Hooker Telescope was cutting-edge for its time, much like the James Webb Space Telescope is today. Built from a 4.5 tonne disc of glass transported from Paris to Pasadena—a journey that took two years—the telescope’s lens is 100” across and is still in use by researchers a hundred years after its construction.

We now look at the stars from among the stars. The Hubble telescope was launched from the Space Shuttle Discovery in 1990 and provides vivid images of the universe without the light interference that disrupts images taken by telescopes from the Earth’s surface. The James Webb Space Telescope launched on Christmas 2021, more than thirty years after the Hubble telescope entered orbit. Both are still trying to answer Hubble’s question: how rapidly is the universe expanding? Scientists long wavered between estimates of 50 and 100 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The Hubble Telescope estimated in 2019 that universe expansion happens at 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Yet only a few months after this discovery, the number was reduced to 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Whether this the expansion is influenced by yet-undiscovered factors, remains to be seen.

Perhaps it’s a question for the next Edwin Hubble. Best keep the doors of the observatory open.