Much has been written about the recent news that the Earth’s temperature climbed to more than 1.5 deg °C above pre industrial years last year, the target set by the Paris climate meeting a decade ago.

Scientists stress that there is nothing magical about the 1.5 °C threshold, in fact it is a poorly defined and arbitrary target that reflected concerns that an earlier 2.0 deg °C target might not be enough to protect low-lying regions from sea level rise.

Prof Tim Osborn of the University of East Anglia commented the longer-term trends in temperature – averaged over more than a decade – are not yet above 1.5 deg °C, though ‘we’re getting close.’

Moreover, the Meteorological Office has confirmed that the world is ‘off track for limiting global warming to 1.5°C.’

Most significant of all, however, there is evidence that the global climate is moving into unknown territory — perhaps more quickly than previously thought – because the past two years have also surpassed scientists’ projections of temperatures made only a year in advance.

‘There is growing evidence of an acceleration in the rate of warming (and the warmth of 2024 added to that evidence),’ said Prof Osborn. He said that a reasonable explanation is a reduction in aerosol pollution, which cuts absorbed sunlight and thus warming, though the trend is still hard to discern in a statistically significance sense.

Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil commented that if the temperature surges in 2023 and 2024 were an indication that global warming is accelerating, ‘we may need to reduce emissions even faster’.

Over the past 12 months, more than one hundred countries have recorded their hottest temperatures ever. Droughts, heat waves, floods, and wildfires have impacted Africa, Southern Asia, the Philippines, Brazil, Europe, the USA, Chile, and the Great Barrier Reef.

Since 1980 for example, climate disasters have cost the USA nearly $3 trillion. ‘As well as devastating communities, as in Los Angeles this month, wildfires also add to climate change,’ commented Prof Richard Betts, Head of Climate Impacts Research at the Met Office, and University of Exeter.

‘The world has seen particularly severe and widespread wildfires two years running, releasing substantial amounts of carbon to the atmosphere,’ added Prof Betts. ‘While some of these are linked to the natural cycle of El Niño (a natural climate pattern that starts in the Pacific Ocean and can affect global temperatures), some have been shown to have been made more intense by human-caused climate change, illustrating the potential for feedbacks to accelerate global warming.’

These feedbacks can lead to rapid and irreversible change to the climate, for instance when a ‘tipping point’ is passed, as is feared may happen in the Amazon, and can also result from ocean heating.

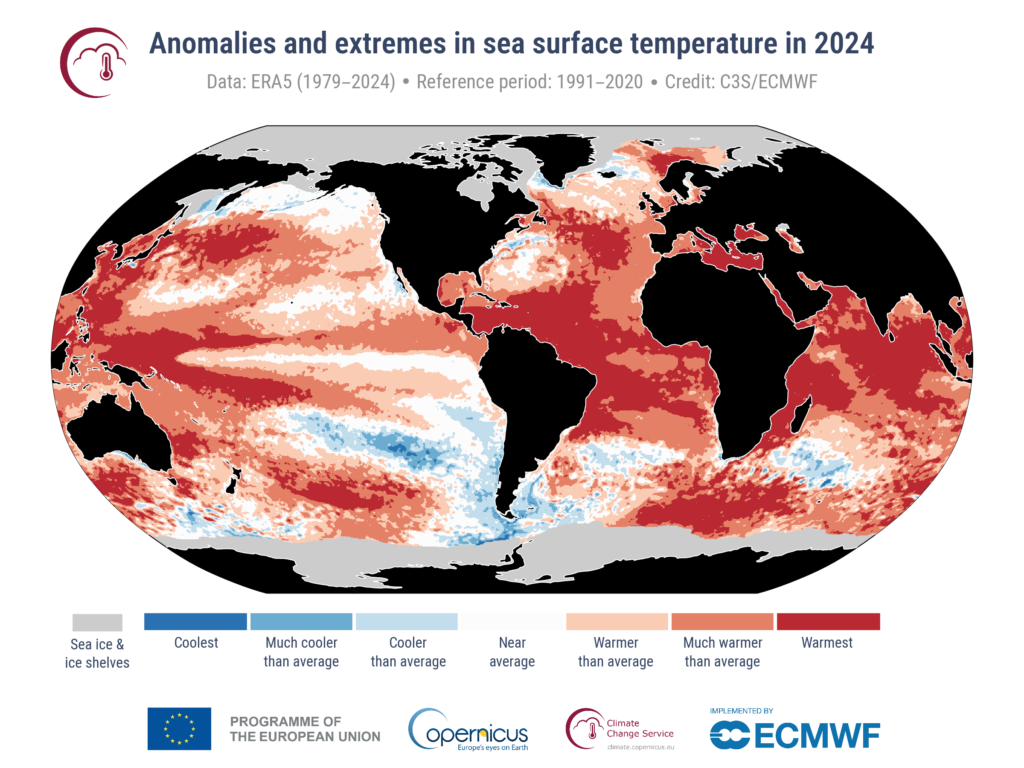

Record high ocean temperatures last year were reported in a study, published this month in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, and the long-term rise in ocean temperatures is not just an effect of climate change but also a cause, because the warmer waters add heat and moisture to the atmosphere.

Water vapour is a powerful greenhouse gas and increased heating fuels storms, notably hurricanes and typhoons, commented Dr Kevin Trenberth, Distinguished Scholar at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, USA. ‘I think now the ocean feedback effects are actually changing the climate… that’s very worrisome, because it has impacts on marine life.’

‘Mass bleaching occurred in the Great Barrier Reef in March, and multiple hurricanes in the Caribbean in July and southeast United States (especially Helene) caused havoc in September,’ said Dr Trenberth. ‘Yagi was a deadly and destructive super typhoon in early September in Southeast Asia and south China and then flooded Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand. Major floods in Chad and Nigeria also occurred in September, and a monstruous deluge in Valencia, Spain in October led to major devastation.’

The ocean is now the hottest ever recorded by humans, not only at the surface but also the upper two thousand meters, which is the most reliable indicator of warming. From 2023 to 2024, the global upper two thousand metres ocean heat content increase is sixteen zettajoules (1021 Joules), which is equivalent to around 140 times the world’s total electricity generation in 2023.

‘The broken records in the ocean have become a broken record,’ commented Prof Lijing Cheng with the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who led the study by a team of fifty-four scientists from seven countries.

The ocean is a critical engine of the Earth’s climate – most of the excess heat from global warming is stored there (around 90%) and, as the ocean covers 70% of the Earth’s surface, it controls how fast climate change occurs and dictates our weather patterns by transferring heat and moisture into the atmosphere.

Dr Trenberth added that the concentrations of CO₂ in the atmosphere are also at record high values. ‘Allowing for the seasonal cycle, the values are now about 425 ppm by volume, more than 50 percent above the preindustrial values of 280 ppm. Indeed, the values are running over 3 ppm above last year, indicating that global heating from increased greenhouse gases continues unabated.’

Last year saw the fastest year on year rise in atmospheric CO₂ concentration in the long-running record of measurements at Mauna Loa, Hawaii, the ‘Keeling Curve’ record, which started in 1958. The measured rise of 3.58 parts per million (ppm) exceeded the Met Office’s prediction of 2.84 ± 0.54 ppm.

The Met Office says that if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C, the build-up of CO₂ in the air already needs to be slowing to 1.8 ppm per year, drawing on calculations used by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).