At the Blythe House object store in west London, over 50 colleagues are working hard to study, record, digitise, pack and transport over 300,000 incredible items from the Science Museum Group Collection to their new home at the National Collections Centre in Wiltshire.

This blog series goes behind the scenes with the teams making this ambitious project happen.

At the very frontline of the project, we are Team Hazards, made up of Katie Thompson, Ben Hill, Emma Turvey, Sarah Kirkham, Miles Deverson and Helen Swan.

Before any of our colleagues can access an object to study, photograph or pack it, we first assess it for hazards. Our team studies each object, recording low risk hazards, noting when no hazards are present and flagging the occasional object with a high risk for further attention by specialist teams.

Thankfully, less than a quarter of the objects we study usually contain a hazard.

We’ve picked out a few of the key hazards we look out for as part of our work:

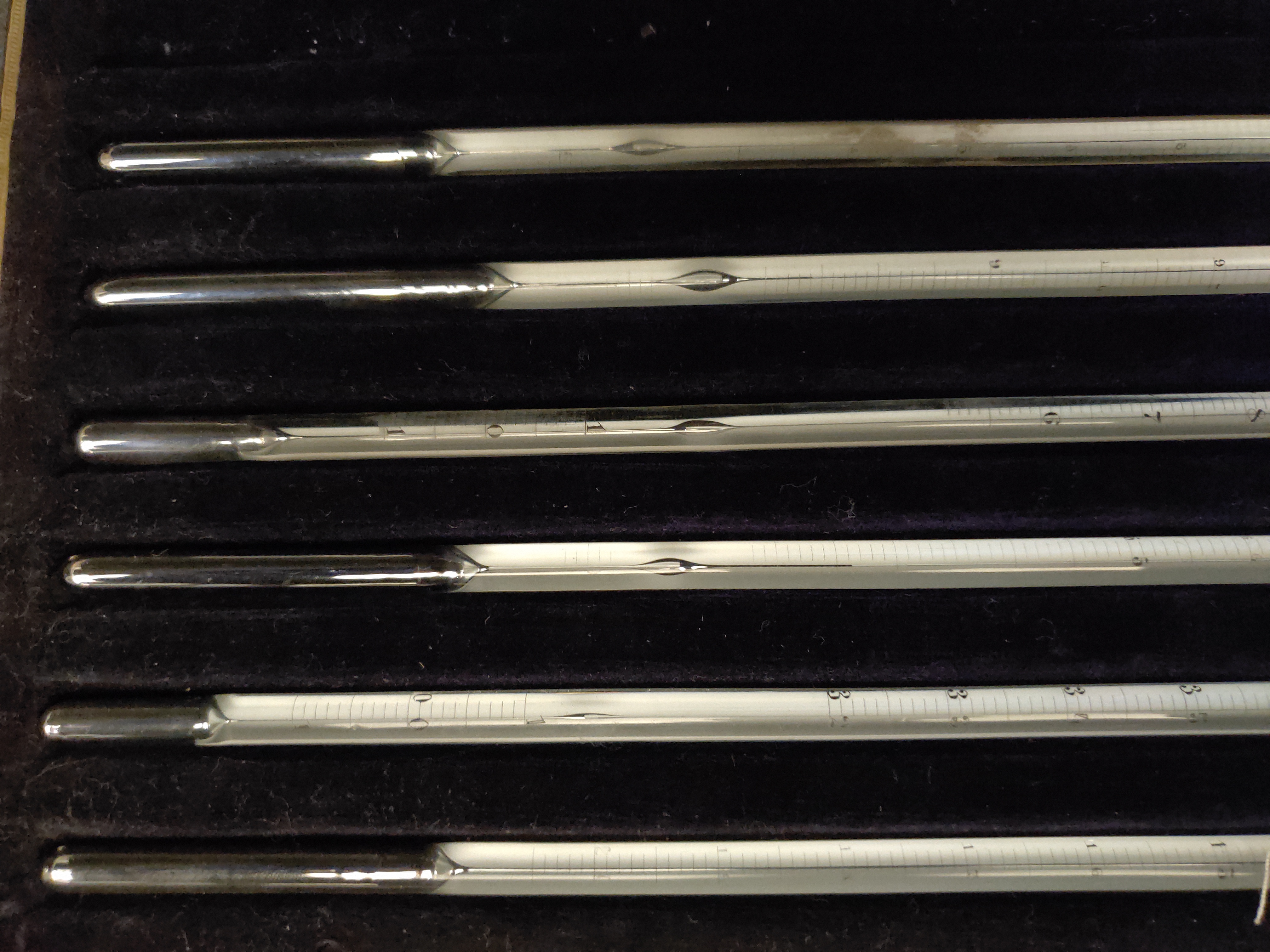

One hazard we are interested in is mercury.

This beautiful shiny liquid metal has toxic vapours and can be poisonous in large quantities. It tends to appear in thermometers and other scientific equipment.

Lead is another hazardous metal we look out for. It is very different in appearance to mercury, instead being heavy and dull in colour.

We primarily find lead being used as a weight, though it can appear in a variety of objects including a lead Roman coffin which we came across as part of our work.

Lead is more hazardous if it has corroded and is covered in white dust. When that happens, the object is given corrosion treatment by our conservation team to reduce the hazard.

Sealed glass tubes used for lighting and scientific experiments are also potential hazards as they often have a vacuum inside so if the glass was damaged it could lead to an implosion and possible injury.

Alcohol, most often found in spirit levels, is also considered a hazard as it is flammable.

Unsurprisingly in the chemistry store we recorded the presence of exotic and unusual chemicals including many boxes of pH indicators. If a chemical is unfamiliar to us or we can’t find the relevant hazards information online, we record it so our curatorial team can carry out further research.

We know that taxidermy and some objects from the ethnographic collection may have been treated in the past with various hazardous chemicals as a form of pest control. Arsenic and methyl bromide are not just hazardous to pests but also to human beings. Even with this knowledge we look out for the tell-tale sign of white residue on these objects which indicates that they’ve been treated with hazardous chemicals.

Another potential hazard is objects which may contain asbestos. Before its damaging effect on human health was known, asbestos was widely used due to its affordability, good insulating properties and resistance to fire, heat and electricity.

Because of this, some objects in our collection contain asbestos and so when we begin a hazard survey of any object, we conduct a Preliminary Asbestos Checklist test.

The test checks whether an object has and one or more of the following, which are signs that asbestos may be present:

- Thermal insulation

- Sound insulation or condensation

- Fire protection

- Steam components or high-pressure connections

- Electrical components or ignition

- Cement-based products

- Friction products

- Textured coverings and coatings

If an object has any of the above it is given a red label indicating asbestos may be present, the reasoning behind this assumption and the level of risk of the hazard.

Most museum objects which contain (or may contain) asbestos are low risk and can be handled safely with care. For the small number of objects which are high risk, our conservators and external specialists work to manage or remediate the risks.

So far our team has surveyed over 100,000 objects for hazards!

This has helped our colleagues know what hazards (if any) are present before they interact with an object and enabled some particularly hazardous objects to be treated by specialists so we can continue to safely care for the objects in our collection.

Once we assess an object for hazards, it’s processed by the inventory team. But more on that in next month’s blog post.

We’ve also shared our work on Twitter, which you can read here: