By scanning people while they watched clips of films, a study has managed to reveal the inner workings of their brains.

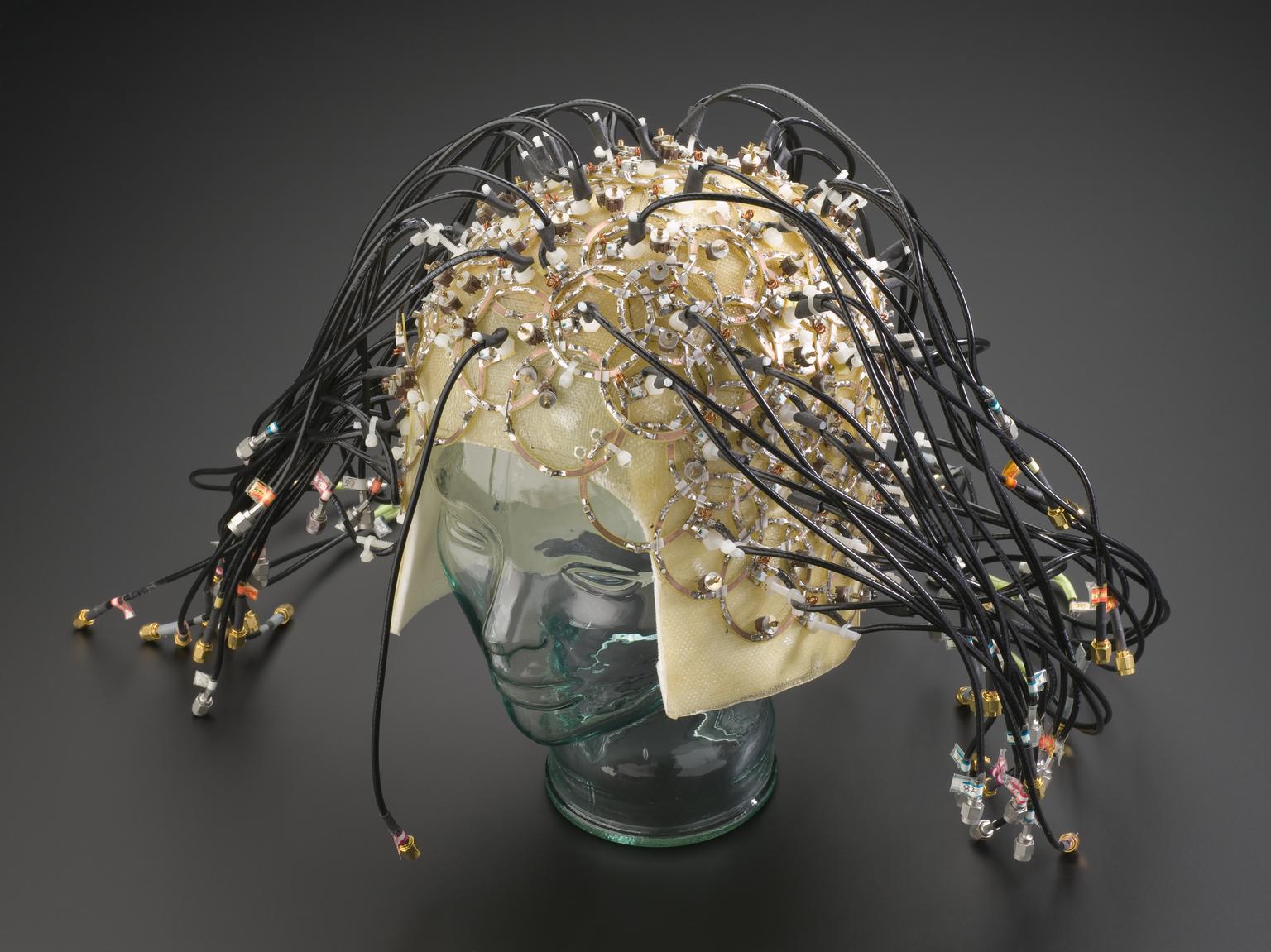

The volunteers were studied by neuroscientists as they watched using a technique called functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or fMRI, which harnesses powerful magnetic fields to reveal tiny changes in blood flow in the brain, reflecting the areas that are working hardest and thus need most oxygen and nutrients.

The fMRI analysis, which is published today in journal Neuron, shows how different brain networks become more active when participants viewed short clips from a range of independent and Hollywood films – including Inception, The Social Network, and Home Alone – to work out which brain area does what.

‘Our work is the first attempt to get a layout of different areas and networks of the brain during naturalistic conditions,’ says first author and neuroscientist Reza Rajimehr of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and colleagues there, at McGill University in Canada, and John Duncan of the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit in Cambridge University, UK.

‘Of the movie clips we tested, a clip from Inception was unique in a sense that it produced huge response fluctuations in many parts of the brain, partly because it was a highly engaging clip and/or it produced a highly similar pattern of response across individuals, resulting in a large response when we averaged data,’ says Rajimehr.

To do the study, the researchers leveraged a previously collected fMRI dataset from the Human Connectome Project, consisting of whole-brain scans from 176 healthy young adults that were obtained while the participants watched 60 minutes’ worth of short clips from a range of independent and Hollywood films.

‘Scanning a large number of subjects in an ultrahigh field scanner (e.g., a 7-Tesla scanner) is definitely not an easy task,’ he says. These scanners can be found only in few imaging centres, the bore of these scanners is small and even a small head movement could cause a large artifact in data.

Their study marks a departure from conventional fMRI scans of people at rest when no specific task is carried out.

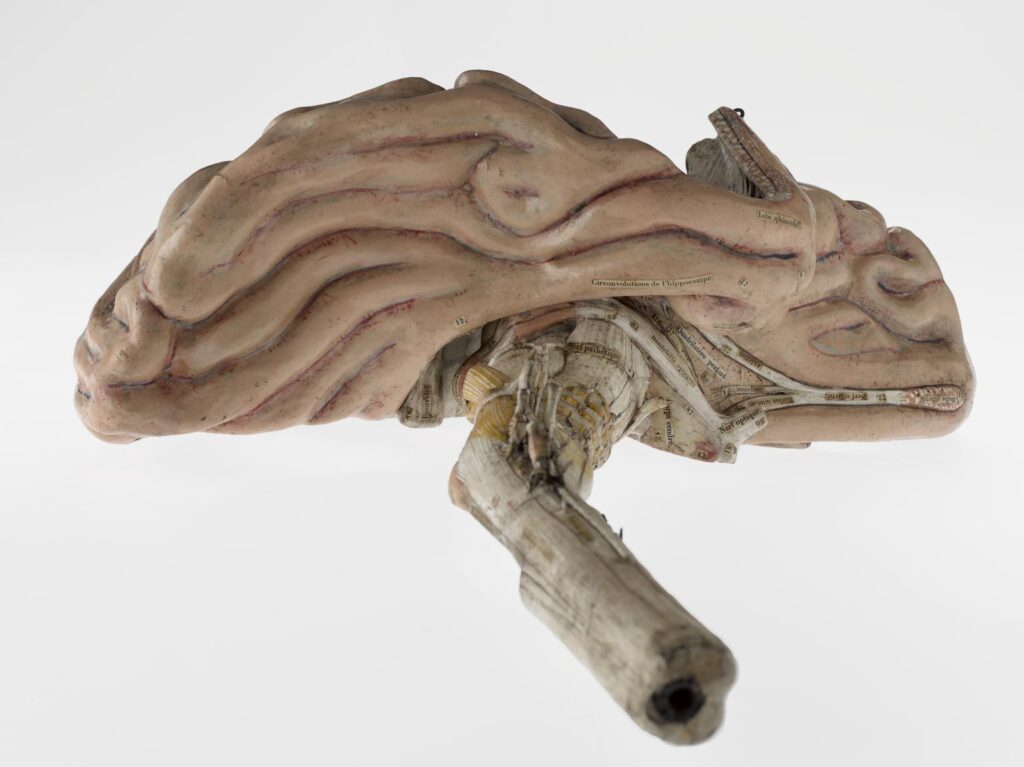

The researchers used a form of AI called machine learning to identify brain networks within the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the brain which is responsible for many of the brain’s functions.

Then, they examined how activity within these different networks related to content in each scene, whether people, animals, objects, music, speech, and narrative. ‘With our movie stimulus, we can go back and figure out how different brain networks are responding to different aspects,’ says Rajimehr.

Their analysis revealed 24 different brain networks that were associated with specific aspects of sensory or cognitive processing, for example recognising human faces or bodies, movement, places and landmarks, interactions between humans and inanimate objects, speech, and social interactions.

The idea that different areas of the brain are strictly dedicated to one job has fallen out of fashion because different areas of the brain are highly interconnected, and these connections form functional networks that relate to how we perceive stimuli from our senses and behave. The team even found a ‘surprise signal,’ triggered in the executive control networks because each clip ended at an unpredictable time.

The team also showed an inverse relationship between ‘executive control domains’—brain regions that enable people to plan, solve problems, and prioritise information—and regions with more specific functions: when the movie’s content was tricky to follow or ambiguous, there was heightened activity in executive control brain regions, but during more easily to comprehend scenes, brain regions with specific functions, like language processing, predominated.

This ensures efficient use of the brain: ‘Executive control domains are usually active in difficult tasks when the cognitive load is high,’ says Rajimehr. ‘For example, if there’s a clear conversation going on, the language areas are active, but in situations where there is a complex scene involving context, semantics, and ambiguity in the meaning of the scene, more cognitive effort is required, and so the brain switches over to using general executive control domains.’

The analyses were based on average brain activities, so future research could tease out how brain network function differs between individuals, between individuals of different ages, or between individuals with developmental or psychiatric disorders.

This ‘would allow us to relate the individualized map of each subject to the behavioural profile of that subject,’ says Rajimehr. ‘Now, we’re studying in more depth how specific content in each movie frame drives these networks—for example, the semantic and social context, or the relationship between people and the background scene.’ In turn, this could give deeper insights into the effects of brain damage, for example.

Last month, at the Manchester Science Festival, I chaired an event on the power of movies to explore neuroscience with Prof Adrian Owen of Western University in Canada, and Paul Franklin, who has won two Oscars for visual effects, notably Inception.

We discussed how (despite the films Limitless and Lucy), we do indeed use more than ten percent of our brains, how far neuroscience can deliver Hollywood visions of downloading skills (Matrix) or even an entire consciousness (Transcendence, Upload), and Prof Owen’s work on using fMRI to ‘communicate’ with vegetative patients (The Diving Bell and The Butterfly.)

In Inception, where Paul Franklin depicted the inner worlds of the brain as a malleable, multilayered landscape, Leonardo DiCaprio plays Dom Cobb, a spy who steals secrets from his victims when they dream, sometimes as they dream within a dream. He can even plant an idea in an unconscious mind, where it can take root.

Prof Owen commented: ‘While the film captures the imagination with its depiction of dream-sharing technology, in reality dreams are often far more chaotic and fragmented than the perfectly scripted dreams we see in Inception. That said, the movie touches on some really meaty neuroscience themes, which I like, such as the existence of repressed memories, as seen in Cobb’s constant battles with projections of his late wife. The notion of ‘inception’ itself is also fun (and timely) because we now live in a world where social media and subtle advertising are constantly seeking to plant ideas in our brains so subtly that they feel self-generated (which is very relevant to the US elections!).’