With Lando Norris’s third place finish in Abu Dhabi this weekend, McLaren have achieved their 13th World Drivers’ Championship in Formula 1.

After an inconsistent first half of the season which saw him trail teammate Oscar Piastri for most of the year, long-time McLaren driver Norris secured his first Championship with 423 points in Abu Dhabi, only two points ahead of defending champion Max Verstappen of Red Bull.

This is the cherry on top of a vintage year for McLaren. They have also secured their 10th World Constructors’ Championship (and their second in a row), with a mighty 833 points from both cars. Their nearest rivals, Mercedes, were a distant second with 469 points.

McLaren have a long history in Formula 1. Second only to Ferrari in longevity, they first entered F1 at the 1966 Monaco Grand Prix.

Founded by New Zealander Bruce McLaren, they have also competed in a number of other racing series, and are currently the only team to have won the motorsports Triple Crown – the Monaco F1 Grand Prix, the Indy 500, and the 24 hours of Le Mans.

Unsurprisingly for such a successful team, McLaren have a track record of innovation in racing. In the late 1960s, the M7 series cars proved a gamechanger, not only for McLaren, but for motor racing as a whole. It was the first racing car to use carbon fibre to reinforce its structure.

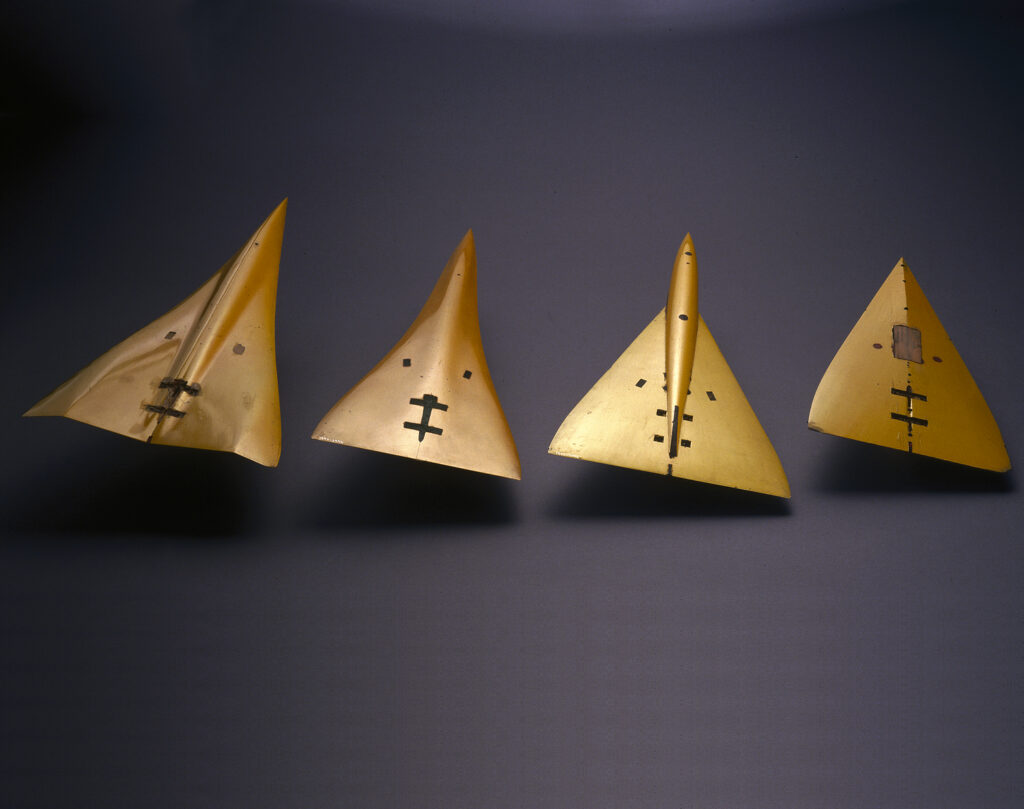

The Science Museum Group has an example of a nosecone of an M7A in the collection – it is a demonstration model, half-painted in McLaren’s iconic papaya colour, and half-unpainted to show off the design below. Made of fibreglass, it is reinforced with black carbon fibre filaments (or ‘bootlaces’) around the inside, which strengthen the whole structure.

This nosecone came from RAE Farnborough, and is in the Science Museum’s Farnborough collection.

It’s an unusual object to find in this collection because Farnborough was an aviation research hub, with both civilian and military research happening on site. It was home to some of the most advanced wind tunnels in the world, and was the British base for the development of Concorde.

However, there are several surprising links between cutting edge aviation science and motor racing.

Two of the engineers working on Concorde, Robin Herd and Gordon Coppuck, left their work on supersonic flight at Farnborough behind to work for McLaren, taking with them their technical expertise.

Their M7 series brought together cutting edge carbon fibre technology with an aerodynamic design, and gave McLaren their first ever F1 winner. With Bruce McLaren himself at the wheel, the M7A was victorious at the iconic Spa-Francorchamps circuit in Belgium in 1968.

In designing the M7 series, it seems the Farnborough connection was crucial. Although carbon fibre has been around in some form since the nineteenth century, a reliable method of producing high-strength, flexible carbon fibre was patented by a team at Farnborough in 1968.

William Watt, William Johnson, and Leslie Phillips were the team who held the patent, and enabled the use of carbon fibre in cars like McLaren’s M7A, and soon after, in many other cars including those racing in 24 hours of Le Mans. They appeared in several press stories about their new discovery with the nosecone as a demonstration of its capabilities.

McLaren have continued to be at the forefront of research and development in F1, and were the first team to develop an all carbon-fibre monocoque (a single-piece, structural chassis), in the McLaren MP4/1, which first raced in 1981 – we have a similar, slightly later version in the collection, the MP4/7, which was driven by 3-time McLaren champion Ayrton Senna.

Carbon fibre design made a huge contribution to driver safety as well as speed, proving the value of carbon fibre as a lightweight but enormously strong material, which protects drivers from high-impact crashes.

Within a year of McLaren’s MP4 debut, most other F1 teams had switched to carbon fibre monocoques, and it remains a foundation of F1 design.

Now, over 50 years later, carbon fibre is firmly established as a wonder material: light weight, durable, and super-strong, it has countless uses. It appears in our collection in tennis rackets, helicopter blades, electric aircraft, and even a robotic bee.