Across vast swathes of the northern hemisphere’s northern latitudes, billions of tons of carbon are locked up in perennially frozen ground – so called permafrost. In permafrost peatlands, this carbon is in the form of remnants of dead plants under an insulating ‘active layer’ of ground that thaws and refreezes annually.

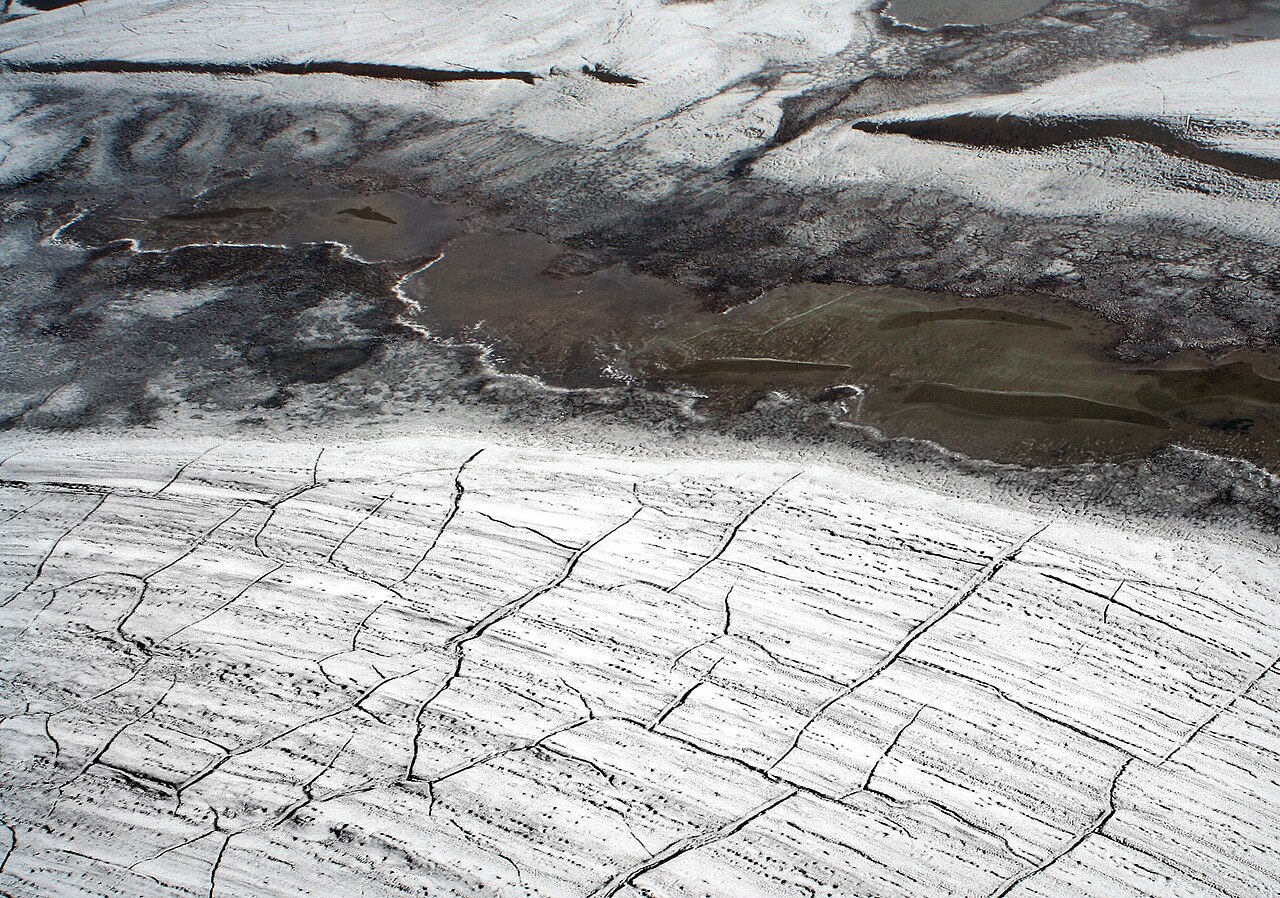

But as global temperatures rise, this permafrost is at increasing risk of thawing, potentially releasing carbon stored for millennia, and leaving a landscape pockmarked by ‘thermokarst’ lakes, filled with meltwater, rain and snow, that release methane, a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

This in turn accelerates the rate at which the permafrost thaws, potentially releasing its long-held stores of carbon into the atmosphere which could push the global climate system past a tipping point, where irreversible change would result.

The new study focuses on predicting when, under various scenarios, the frozen peatlands of Europe and Western Siberia will be at risk of climate-induced permafrost thaw, which store an estimated 39 billion tons of carbon – the equivalent to twice the carbon locked up in all the forests of Europe.

To understand how these frozen peatlands could behave in a range of future climate scenarios, from taking no action to different degrees of mitigation, the latest generation of future climate projections were analysed in an international study led by the University of Leeds, published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Study co-author Dr Paul Morris, Associate Professor of Biogeoscience at Leeds, commented that under high future warming scenarios ‘all that stored carbon can be lost very quickly.’

Study lead author, Richard Fewster, added that their modelling shows ‘these fragile ecosystems are on a precipice and even moderate mitigation leads to the widespread loss of suitable climates for peat permafrost by the end of the century.’

Even with the strongest efforts to reduce global carbon emissions, the models suggest that by 2040 the climates of Northern Europe will no longer be cold and dry enough to sustain peat permafrost.

‘But that doesn’t mean we should throw in the towel. The rate and extent to which suitable climate are lost could be limited, and even partially reversed, by strong climate-change mitigation policies,’ said Mr Fewster.

As one example, concerted action to reduce emissions could preserve permafrost peatlands in northern parts of Western Siberia, a landscape containing 13.9 billion tonnes of peat carbon, one third of the carbon in the study.

Study co-author Dr Ruza Ivanovic, Associate Professor in Climatology at Leeds, added that peatlands remain poorly represented in computer models of the Earth’s climate system. ‘It is vitally important these ecosystems are understood and accounted for.’

More data should be gathered by satellite and field studies about these frozen stores of carbon, according to co-author Dr Chris Smith, from the School of Earth and Environment.

Deeper understanding is crucial because scientists estimate that there is about twice as much carbon stored in the permafrost as circulating in the Earth’s atmosphere. If the organic matter within permafrost decomposes and releases CO2 and methane, there is no easy way to get it back.

However, the overall impact of thawing is complicated by another important factor, the carbon uptake by plants, which can alter the carbon balance of the permafrost zone.

Arctic temperatures have been increasing more than twice as fast as the global average and permafrost thaw has already been observed in many locations. A 2019 special report on the ocean and cryosphere by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) pointed out that warming this century will cause substantial emissions from permafrost: ‘with the potential to accelerate climate change.’

Another recent study reports thawing of permafrost submerged underwater at the edge of the Arctic Ocean.

There are other tipping points, for instance when it comes to the Amazon rainforest, the focus of our Amazônia exhibition that is about to transfer to the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester.

The fear is that a global cascade of such tipping points could push the Earth’s climate system into a significantly less habitable ‘hothouse’ state.