At one-thirty in the afternoon on 30 January 1890 the steamship Bothnia moored at New York Harbor, ending a stormy 11-day voyage across the Atlantic. Shortly after Elizabeth Bisland (11 February 1861 – 6 January 1929) stepped ashore, cheered by hundreds of friends and well-wishers.

Bisland was no ordinary passenger. Just 76 days earlier she had departed New York’s Grand Central station on a westbound train, in a bid to circumnavigate the globe faster than Phileas Fogg, the fictional creation of Jules Verne in his 1873 novel Around the World in Eighty Days.

Bisland was a journalist for The Cosmopolitan, an American monthly magazine that aimed to acquaint its readers with people and places around the world (it still exists today but in a different guise).

Bisland embarked on her journey merely hours after her editor had come up with the idea, and her account of her travels was serialised in the magazine before being published as a book.

Though Bisland succeeded in beating Fogg, her circumnavigation was not the fastest in history.

Just four days earlier on 26 January, fellow journalist Nellie Bly—who had departed New York at the same time as Bisland, headed in the opposite direction—had returned triumphantly to claim that prize.

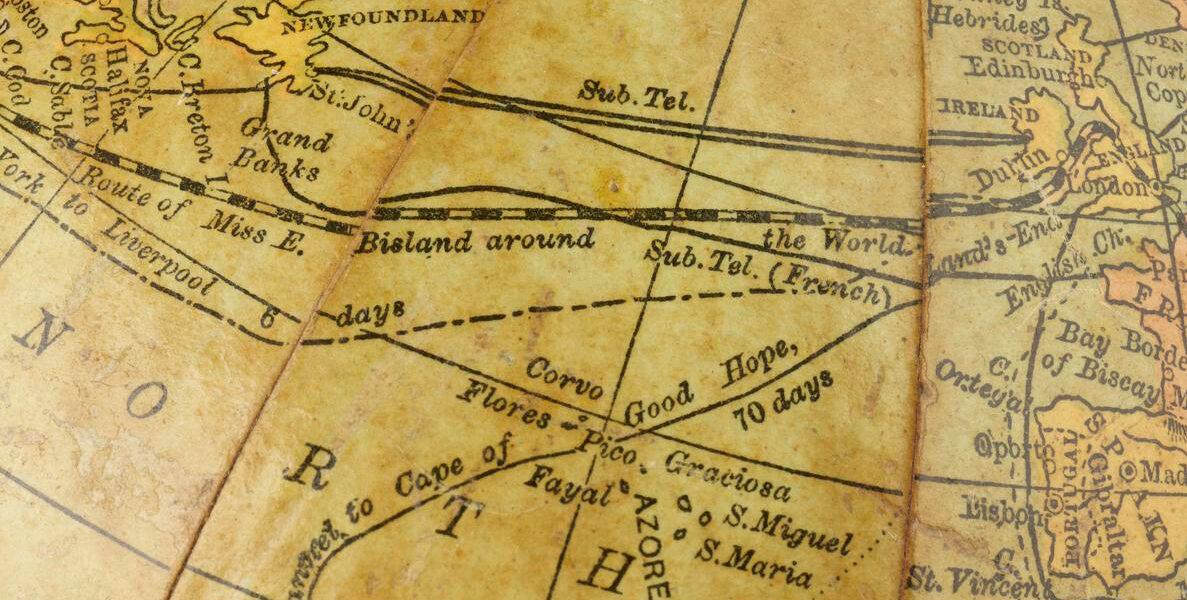

Bisland’s journey is captured on this quirky little globe, one of the most recent acquisitions to the Science Museum Group Collection. It shows her route westwards across North America, across the Pacific to Japan, by ship via Hong Kong, Colombo and the Suez Canal, by rail through Europe and then finally across the Atlantic.

In celebrating the journey of a female traveller, it is extremely rare. In the 1700s it was commonplace for globes to memorialise the voyages of national heroes (in Britain, these included James Cook and George Anson), and to glorify maritime achievements and colonial conquests (such as in this Dutch example from 1599).

Such journeys that were framed as ‘heroic’ continued to be a male domain long after it was common practice to inscribe them on globes. As Bisland and Bly set out on their respective adventures, their gender contributed to the press sensationalism surrounding their voyages.

As Abi Wilson, Curator of Transport and Mobility, points out, the globe also carries fascinating information about the infrastructure that characterised Bly and Bisland’s world: ‘The globe shows many of the common steamship routes with their duration in days, the network of which inspired Jules Verne’s novel,’ she explains. ‘It also shows the location of the submarine telegraph cables that were the backbone of Victorian communications.’

By the late 1800s, many people felt this infrastructure was effectively shrinking the world.

Kevin Riordan, Assistant Professor in the School of Humanities at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, believes it is significant that ‘you literally can hold this diminutive globe in your hand,’ reflecting how the world had become newly accessible. He notes how at this time, ‘people started imagining the previously abstract “global” on the scale of the individual. Bisland’s illustrated route on the world’s surface portrays this personalisation. The world was something one could hold, travel around, and even in some sense do, on a seventy-six-day trip like Bisland’s.’

The globe is not as finely made as other terrestrial globes in our collection. Its stand is basic and inelegant, and its printed paper segments (known as gores) are misaligned. It seems not to be the work of a highly skilled globemaker (this video shows how globes are made).

There are many unanswered questions about the globe, including who made it and why. One plausible theory is that it was commissioned by The Cosmopolitan to celebrate Bisland’s journey, perhaps when the editor believed she would beat Bly (whose journey is absent from the globe).

We look forward to studying the globe more closely to discover its secrets.