The Collections Review Team researches our collection to learn more about our objects and bring their stories to light. Recently, the team has been reviewing some of the objects in the Earth Science collection and became fascinated by the objects related to tides and currents that emerged in the process of the research.

The movements of the sea are shaped by tides and currents. Tides originate from the gravitational pull of the Moon, and the interaction between the Moon, Earth, and Sun, which creates the rise and fall of coastal water levels. Currents, on the other hand, are shaped by various forces, and move masses of water across distances. There are many : surface currents, deep sea currents, saline or freshwater currents; tidal currents, currents of different temperatures, currents that cross whole oceans, and currents that only move for short distances.

These movements affect our everyday lives. They shape weather events, such as El Niño and make storms – it’s the interactions between wind, tides, and currents which mean the UK has milder winters than other places at the same latitude, like North America. Understanding these movements helps us understand weather patterns, the migration of fish and other sea life, or how hazardous material like oil leaks might travel.

The Science Museum Group Collection includes numerous objects dedicated to understanding or measuring the movements of the oceans, especially since, as an island, the UK has a particularly rich history in designing and using such objects.

Here are some of our highlights.

Understanding tides and currents

The evolution of technology to understand tides and currents can be traced through our objects.

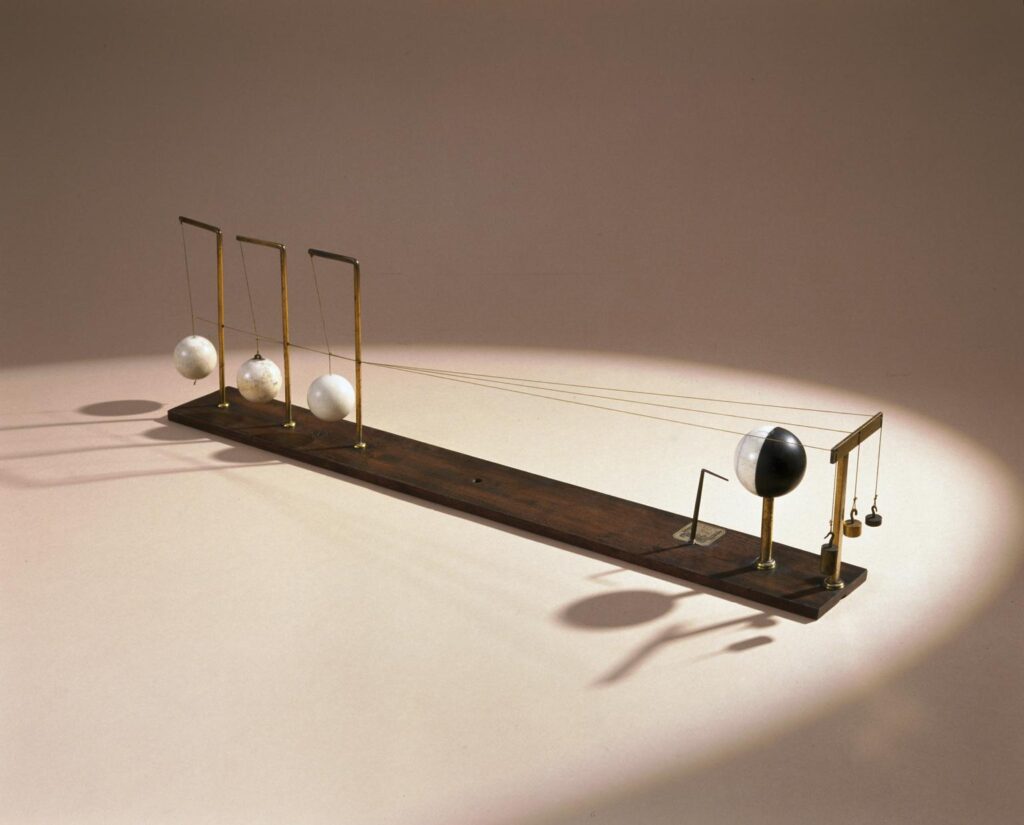

George III was fascinated by science and commissioned a large suite of instruments to educate himself and his family. This tidal motion apparatus was made in 1762 for the King by George Adams. It demonstrates tidal motion through a simple mechanism using weights.

To see it in action you would turn it around. The black and white ball represents the Moon, the central ivory ball represents the Earth, and the other two balls represent the water on each side of the Earth. The weights imitate the gravitational pull of the Moon. When the base was spun around the central hole at a certain speed, the Earth ball hung vertically, and it was seen that the ‘water’ rose on each side of the Earth. It would have been attached to the larger Philosophical Table which is also in the collection.

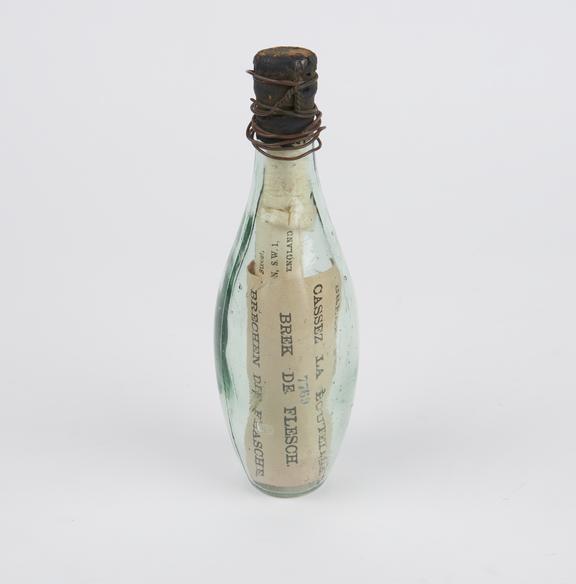

Drift bottles like the one pictured above were used by scientists in the late 1800s up to the 1960s to understand ocean surface currents. Transparent bottles were released in a recorded location and contained a notice in different languages that invited those who discovered the bottle to break the glass and send the new location back to the scientists.

While drift bottles are a very simple way to measure currents, they can still play a valuable role in oceanography research.

A rather more technically advanced way to record currents for the time is demonstrated through this helix current meter. It was made around 1965 by Hilger & Watts Ltd, a leading manufacturer in scientific instruments in the UK. This mechanical instrument measures currents speed by counting the rotation of the propeller as well as the direction of the flow.

As technology has evolved, different techniques to record currents have been explored, such as using sound (sensing the movements of water acoustically), magnetic fields (measuring the flow through electric currents generated by the Earth’s magnetic field), or imaging (using sequential images to follow and record particles caught in a flow).

Utilising technology to work with tides and currents, then and now

Some objects in the collection explore how the tides and currents have been – and are being – used to shape our world, from winning battles to tackling environmental issues.

The tide predicting machine, created by William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) in 1872, and built by A. Légé & Co, is a mechanical analogue computer that uses astronomical combination to draw the tidal curve of a location (you can see it on display in Mathematics: The Winton Gallery at the Science Museum). Throughout the late 19th century and 20th century, tide predicting technology evolved and was used for an array of purposes, notably during World War II when it provided important data for the Normandy landings.

The success of the landing was partly due to the clever use of the tides. The Allied forces were anticipated by the Germans to land at high tides, who placed obstacles in the intertidal zone. To counteract this, a late rising moon and a low tide just before sunrise meant the coastline could be approached in darkness so that the paratroopers could land unseen, use the first lights to fire before the landing, and send a team to remove the obstacles. The tide predicting machines were used to predict the precise hours and days in which it could be feasible.

This Friendly Floatee toy was found on the coast of Sitka, Alaska. Marine debris, and particularly plastics, have been recognised as an important issue in our current environmental crisis.

Research exploring the issue includes the scientific study of the plastic toys such as the Friendly Floatee, which fell off a container ship in 1992 in the North Pacific. The location and time of the beaching of these toys are helping oceanographers improve their understanding of ocean surface currents, and how plastics travel across oceans.

For more information about this series of objects, listen to the Brief History of Stuff podcast.

These weathered Lego bricks fell into the sea off the coast of Cornwall in 1997 and are still being found across beaches.

Reports of these findings are contributing to a collaborative research study on the durability of plastics at sea with the University of Plymouth, by assessing the toxins released through degradation and their impact on marine ecology.

This tidal turbine blade was launched in 2016 off the coast of the Orkney Islands as part of a test programme (the Orbital Marine Power’s SR2000 Turbine). Over 12 months, it generated over 3GWh of electricity, enough to power 1000 homes. You can see the turbine blade on display in Energy Revolution: The Adani Green Energy Gallery at the Science Museum.

This piece of technology is an important development in our history of understanding and working with tides and currents. It illustrates the current efforts to combat climate change by using sustainable energy generated the ocean.