When people think about museums in general, what usually comes to mind is a place where we go to learn about the past of humanity and the natural world. It’s like a repository of knowledge. It is true of course that museums give us a glimpse of the past, a better understanding of our history and our place in the world, but is it all there is to it?

Science museums are different. Although they are also a repository of scientific knowledge, they have to account for the fact that science is not written in stone. It’s one of the beautiful aspects of science, it changes with new evidence about how things work, and suddenly, something that was believed to be true in the past can be contested. But how do we fit this into a museum exhibit? How can we make sure that people get not only the current knowledge about science, but also the information that science is a self-correcting activity, where knowledge can change?

To answer this question, I’d like to focus on two main aspects: the first is science education, and the second the relativity of wrong.

Science education has to change, and museums can help. All around the world, science is usually taught as this great body of knowledge, that students must memorize, because it will be on the test, with yes and no answers.

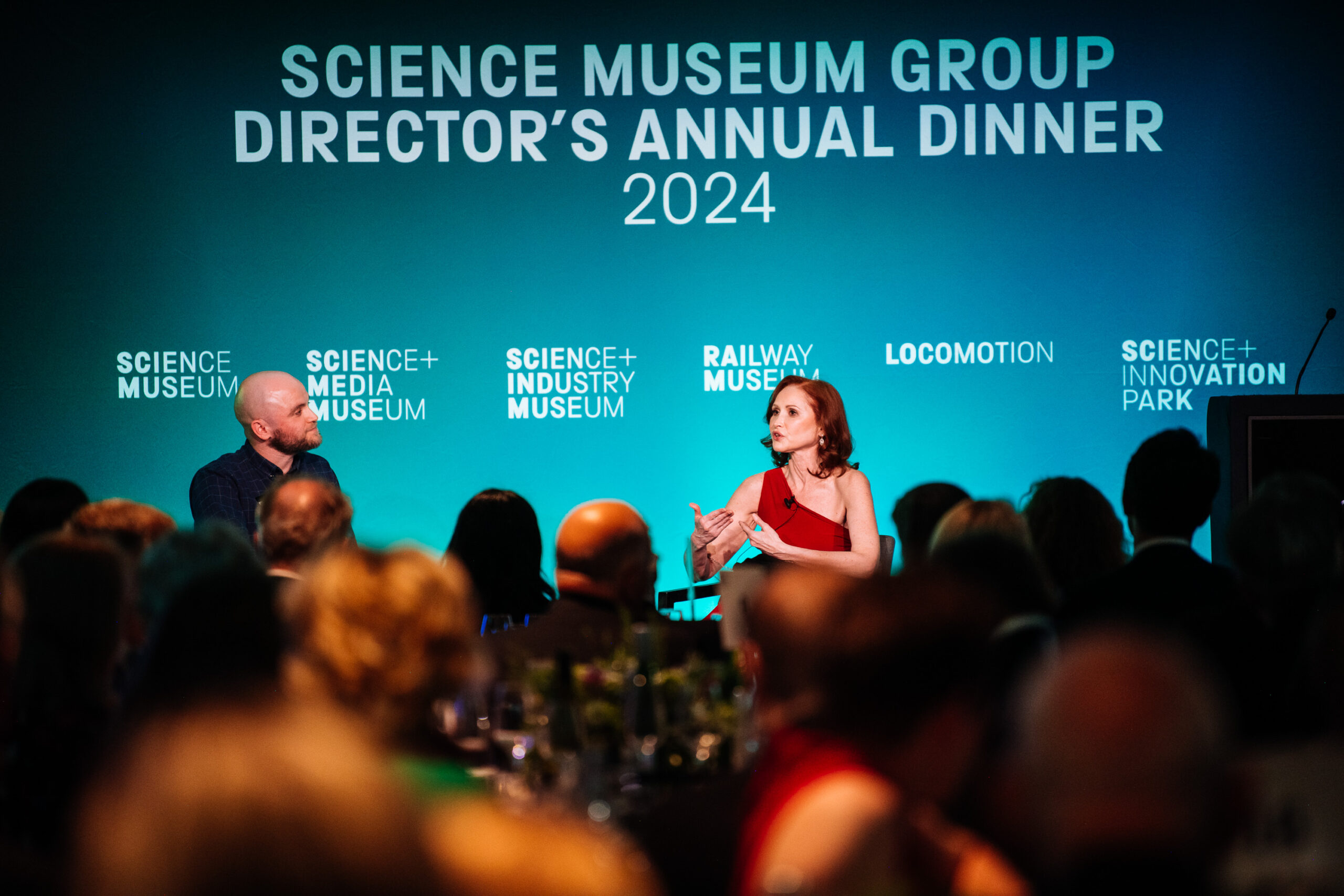

Last week I had the privilege of being the honoured guest and keynote speaker for the Science Museum Group’s Annual Dinner, and this sentence got a good laugh from the audience, so I know it resonated with how many people there were taught in school.

I added that I couldn’t think of anything less scientific than yes and no answers! This is just not the way we do science. But when we teach it like this, it creates impossible expectations in the public. People want the right and wrong, yes or no science, like they learned it in school. And then, as scientists, we are surprised when some people get suspicious of new COVID-19 vaccines. Nobody explained to them how a vaccine really works, what efficacy really means, and how we test it in clinical trials. We must do better. We must start focusing on teaching the process of science, not the results. By teaching how we use the scientific method, and how we establish scientific consensus, we might be able to stop the impossible expectations and build trust.

Which brings me to my second point: the relativity of wrong. What scientists don’t know can be frightening to the public, and when scientists change their mind as a result of new evidence, it can be even scarier. As scientists, we are used to changing our minds, and making mistakes, and failing again and again in experiments. The public isn’t. After all, they get the results, and not the process, so they often don’t know how much change, failure and repetition is involved in scientific research. So, we must show them. But we must be careful in clarifying that recognizing our past mistakes doesn’t automatically render everything useless.

Isaac Asimov wrote an essay back in 1989 for the Skeptical Inquirer magazine titled ‘The relativity of wrong’. It came out after a letter he received from a literature student, claiming the since science had been wrong about so many things in the past, one simply couldn’t trust it to be right. Asimov replies that this feeling probably comes from the notion the right and wrong are absolute, and ‘that everything that isn’t perfectly and completely right is totally and equally wrong’. He goes on to say that believing that the Earth is flat is wrong. Believing that it is a sphere is also wrong. But believing that flat earth is just as wrong as spherical Earth, is wronger than both!

I believe that science museums can promote critical thinking, especially in teenagers and young adults, by teaching them about the scientific method and the process of science, and how by using this to develop knowledge and technology, we can be less wrong.

Following Natalia Pasternak’s remarks, Professor Jim Al-Khalili, Dame Julie Maxton, Ellen Stofan and The Lord Willets were each presented with Fellowships of the Science Museum Group by Sir Tim Laurence, Chair of Trustees of the Science Museum Group, as part of the 2024 Science Museum Group Annual Dinner.

Professor Jim Al-Khalili was recognised for his work as a nuclear physicist and quantum biologist, as a notable science populariser, ranging from TV and books to The Life Scientific, and for his participation in Science Museum Group projects and events.

Dame Julie Maxton was recognised for her work as Executive Director of the Royal Society, helping to forge a range of closer collaborations, from exhibits to committees and events, with the Science Museum Group.

Ellen Stofan was recognised for her work as Under Secretary for Science and Research at the Smithsonian, as the John and Adrienne Mars Director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (2018–21), as Chief Scientist at NASA (2013–16), and for engaging with the public, whether through books, events or lectures, including one at the Science Museum.

The Lord Willets was recognised for his work as Chair of the UK Space Agency, as Minister for Universities and Science, when he visited the Science Museum to announce the UK’s first official astronaut, and as a Trustee of the Science Museum Group, when he led the way in drawing up a

new strategy.