In 1930, a group of leading British mystery writers formed the Detection Club, including Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. To join this elite cadre of crime authors, one first had to make an oath.

With tongues firmly in cheek, members committed themselves to upholding the rules of ‘fair-play’ so that readers could guess the guilty party in their works. They promised to create plots that did not rely on ‘Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo’ and that Death-Rays, trapdoors and super-criminals would be used only in ‘seemly moderation’.

But, the authors swore, they would ‘utterly and forever […] forswear Mysterious Poisons unknown to Science’.

The ‘Golden Age of Detective Fiction’ covers classic murder mystery novels written around the 1920s and 1930s. These books tended to be light-hearted ‘cosy’ crime, within which you could reliably expect to find upper-class characters in a secluded country estate, where at least one of them usually died.

Agatha Christie employed poison more than any other murder method in her books. During World War I, she volunteered with the Red Cross and eventually qualified as a dispensing apothecary’s assistant. She killed off more than 30 characters by poisoning throughout her 66 mystery novels. She didn’t know ballistics – she knew chemistry, pharmaceuticals and poisons.

‘Give me a decent bottle of poison,’ she said, ‘and I’ll construct the perfect crime’.

TOXIC SHOCK: WHY WERE THEY FOR SALE?

But if the poisons must not be ‘unknown to science’, where were the murderous villains of literature getting such lethal concoctions?

Poisons were – and in some cases still are – available for purchase in pharmacies and chemists because, in small doses and in the right circumstances, they provide medicinal benefits. They were also available because they were poisonous, which could be useful for a rat or pest problem.

What’s your poison?

Strychnine

Strychnine was commonly used as poison for rats or other stray animals. With a long history of varied use in herbal medicine in East Asia, it was gradually introduced into Europe where alongside pest control it was used in small doses as a stimulant for muscle contractions. Strychnine was an ingredient in ‘tonics’ such as Ner-Vigor – which could be prescribed for conditions as varied as clinical depression, rickets and sciatica.

It was also used for stamina: medical students took it when cramming for tests and perhaps most famously, in 1904, marathoner Thomas Hicks took strychnine with brandy to overcome tiredness. He won an Olympic Gold and collapsed at the end of the race. It shocks the nervous system in the same way as caffeine, except the lethal dose is much, much smaller: only 5mg.

As late as 1973, there were cases of accidental strychnine poisoning from tonics that used it as an ingredient. Reflecting on the case of a thirteen-month-old, who swallowed one such tonic, two doctors wrote to the British Medical Journal: ‘As strychnine has no proved clinical value and is a known poison, does commercial success in so-called “tonic” sales outweigh the risk of unnecessary fatalities?’.

SPOILER: Agatha Christie used strychnine poisoning in her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. The murder is brought about by mixing the victim’s evening tonic, which contained a non-lethal amount of strychnine, and sleeping powders, which contained bromide. The bromide caused the otherwise soluble strychnine sulfate to become insoluble and sink to the bottom of the tonic bottle. The final dose, consumed when the bottle was nearly empty, was a lethal concentration.

Cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring chemical and can be found in seeds and stones of fruit such as almonds, apples and peaches.

In 1880s Europe, it was thought that cyanide was a powerful antiseptic. Initially devised by Joseph Lister, in World War I Cyanide Gauze was used in the field to provide antiseptic treatment to the skin being bandaged. Less toxic antiseptics would go on to replace it.

Cyanide was also used as a coin cleanser in the 1920s – but a dangerous one. In 1922, coin-collector J Sanford Saltus died in his hotel room. On his dressing table were two glasses: one of ginger ale and one of potassium cyanide coin cleanser. It’s thought he drank from the wrong one.

Primarily, potassium cyanide was available to purchase over the counter as a pesticide, mostly for rats.

SPOILER: In Ngaio Marsh’s Death at the Bar, the victim is poisoned in a private room of a pub. The investigation reveals that, in the first aid cupboard, the landlord kept a bottle of potassium cyanide to kill rats. The murderer laced iodine with the rat poison and then used it to clean out a small wound, ultimately killing the victim.

Arsenic

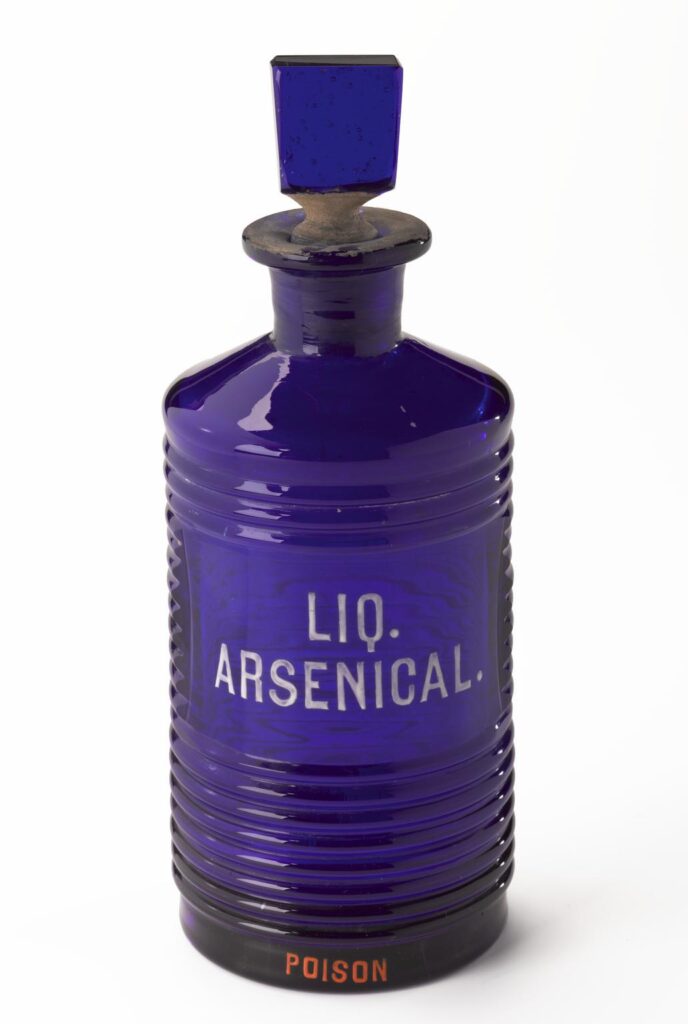

Arsenic naturally occurs in minerals. With unspecific poisoning symptoms, it became known as ‘inheritance powder’ from its use in removing relatives. A sensitive and reliable method to detect arsenic poison was developed in the 1830s – it was one of the first poisons detectable through forensic testing.

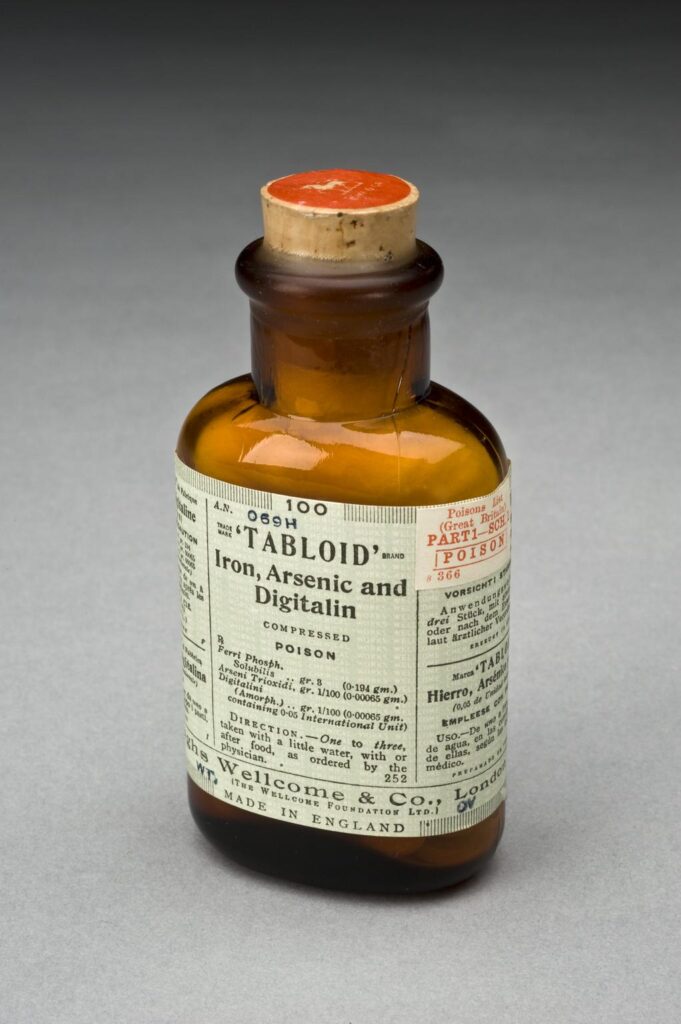

Arsenic had a variety of uses – it was a pest poison; useful in embalming and taxidermy; and could even be used as vivid green pigment dye for textiles. It was used to improve complexion and Fowler’s Solution, a 1% solution of potassium arsenite, was still being recommended for psoriasis in textbooks into the 1960s.

Arsenic also led to some of the first effective drugs to treat the disease, syphilis. Created around 1910, Salvarsan is an antimicrobial drug made of synthesised arsenical compounds. Its poisonous nature was found to be effective at killing the bacteria that cause syphilis but it was complicated to make and unstable. In the 1940s, it would be supplanted as a treatment for syphilis by penicillin.

Even now, arsenic trioxide is used to treat certain blood cancers.

SPOILER: In Strong Poison by Dorothy L Sayers, the victim is found to have died by acute arsenic poisoning. Complications arise when all he ate that day was shared with others who presented no ill effects. The culprit had built a tolerance for arsenic and was able to share a spiked omelette without the fatal outcome. It should be noted that science now suggests that long-term consumption of arsenic would cause health issues.

Chloral Hydrate

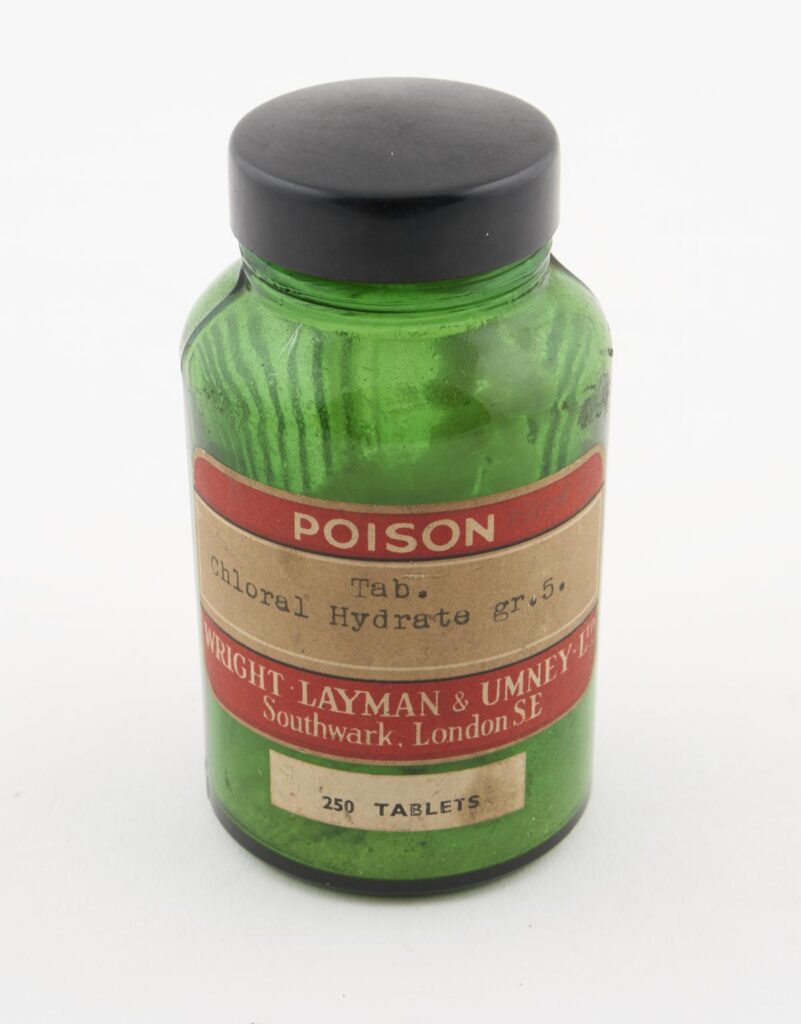

Chloral hydrate was first synthesized in 1832 and is not naturally occurring. Its sedative properties were noted in the 1860, when it became commonly used to treat insomnia and calm anxiety. For many years, it was administered to sedate children before dental or medical procedures. In adults, it was also used to treat the symptoms of withdrawal of alcohol and other drugs such as opiates and barbiturates. It is itself addictive.

Chloral hydrate is soluble in both water and ethanol. A solution of chloral hydrate in ethanol, called ‘knockout drops’, was used to prepare a ‘Mickey Finn’, where we get the phrase to ‘slip someone a mickey’. Mickey Finn managed a saloon in Chicago in 1903 when he was accused of using knockout drops to incapacitate and rob his customers.

SPOILER: In The Seven Dials Mystery by Agatha Christie, the victim dies in his sleep, with a bottle of chloral (chloral hydrate) on his nightstand. Ruled an accidental overdose, suspicion is raised as he wasn’t known to take sedatives.

Strong Poison: Where did people buy them?

Until the 1850s, there was very limited regulation of poisonous substances: they could be bought over-the-counter in local shops and even dispensed into whatever container you brought from home.

In 1851 the UK’s Arsenic Act was introduced to address public concern over accidental and deliberate arsenic poisonings. For the first time, sales of arsenic had to be recorded in a register and only sold to an adult. At this point there was no restriction on who could sell arsenic: there was no legal definition of a chemist or druggist.

The act was limited in its impact – only a few years later in 1858, 20 people died and hundreds were left ill from a batch of sweets accidentally laced with arsenic. Instead of using plaster of Paris to bulk out the sweets, arsenic trioxide – a white, odourless powder – had been mixed in.

In 1868 the Pharmacy Act set up a register of people qualified to sell, dispense and compound poisons, managed by the Pharmaceutical Society. It also established a system for the distribution of fifteen named poisons, including strychnine, potassium cyanide and ergot.

All poisons purchased had to be entered into a Poison Register which included the purpose for which they were bought. They could only be sold if the purchaser was known to the seller or to an intermediary known to both. All drugs had to be sold in containers with the seller’s name and address.

This was intended to create a traceable line: if someone died, a police officer could check the purchases in the local area. It was a low bar for prevention. In Strong Poison by Dorothy L Sayers, Harriet Vane, a crime novelist, tests how easy it would be for a character in her book to collect a lethal dose of arsenic by visiting multiple chemists and signing different names in the Poison Register. The answer is very. Then again, when her husband is found dead by arsenic poisoning, her trips come under suspicion.

There had been a growing demand for ‘safe’ bottles to store poisons in for many years. These were to avoid accidental poisonings and medication mix-ups. The bottles came in bright, ridged glass, often vibrant blue or green. They were designed to be instantly recognisable by touch when feeling around in the dark and by sight. It wasn’t until 1908 that the Poisons and Pharmacy Act made it law that bottles that contained poison were clearly labelled as such.

Poison Pen: Why were poisons so popular in crime fiction?

Nowadays, there’s much tighter regulation on the sale of poisons. There are bottles that aren’t just ridged to prevent accidental consumption, but have tamper-proof tops to prevent children accessing them. We have toxicology reports and improved testing to identify poisons in the body.

But poisons suit the intellectual conundrums posed by those classic detective novels. As a plot device, they enable trickery, which places emphasis on the reasoning of the reader and the fictional detective to solve the case. That logic is also why ‘Mysterious Poisons unknown to Science’ just would not do; instead, authors used the dangers that lurked in everyday substances. They showed how the ordinary could be turned lethal.

Discover the services offered in a typical pharmacy in 1911 by stepping inside Gibson and Son’s at the Science Museum’s Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries. Gibson and Son’s Pharmacy served Hexham for 140 years until it closed in 1978. Its contents were acquired by the museum, much of which is on display in this recreation.