Imagine if you could enter a personal museum about the world’s most famous scientist, one containing the pictures, trophies and other things that had been collected and curated by that self-same scientist.

When it comes to Stephen Hawking, you can.

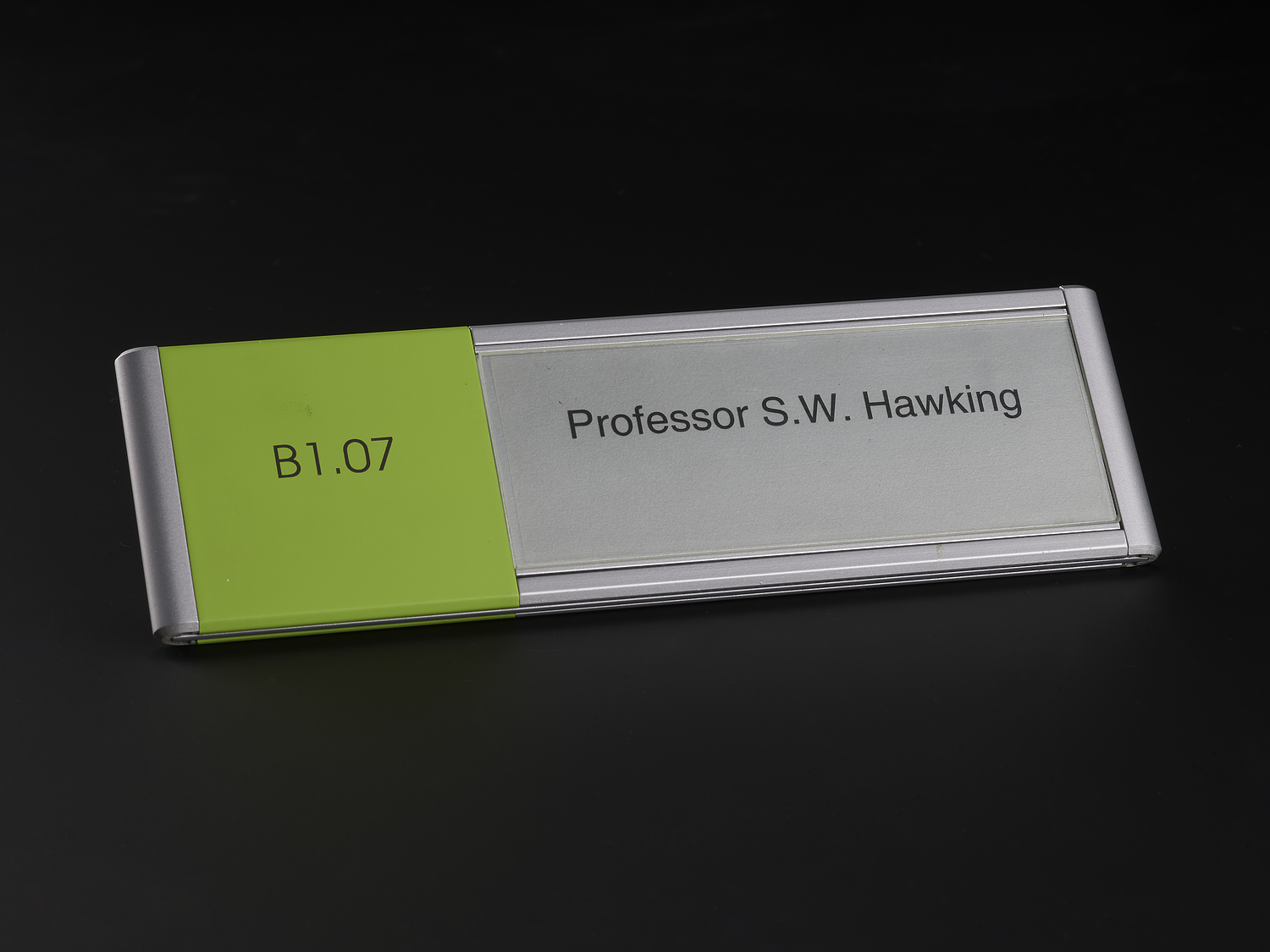

Behind this sign lay the office of the world’s best-known physicist of recent years. The contents of the office were collected by my former colleagues, Tilly Blyth, and Ali Boyle, thanks to the nation’s Acceptance in Lieu Scheme, and now form part of the Science Museum Group Collection.

Since they were collected they have been studied by my colleagues, notably physics curator, Juan-Andres Leon, and form the basis of an exhibit in Manchester.

In Stephen Hawking: Genius at Work, I describe many of these objects and how they can unlock the secrets of his extraordinary science and no less extraordinary life.

Here are a few of my favourites from the book:

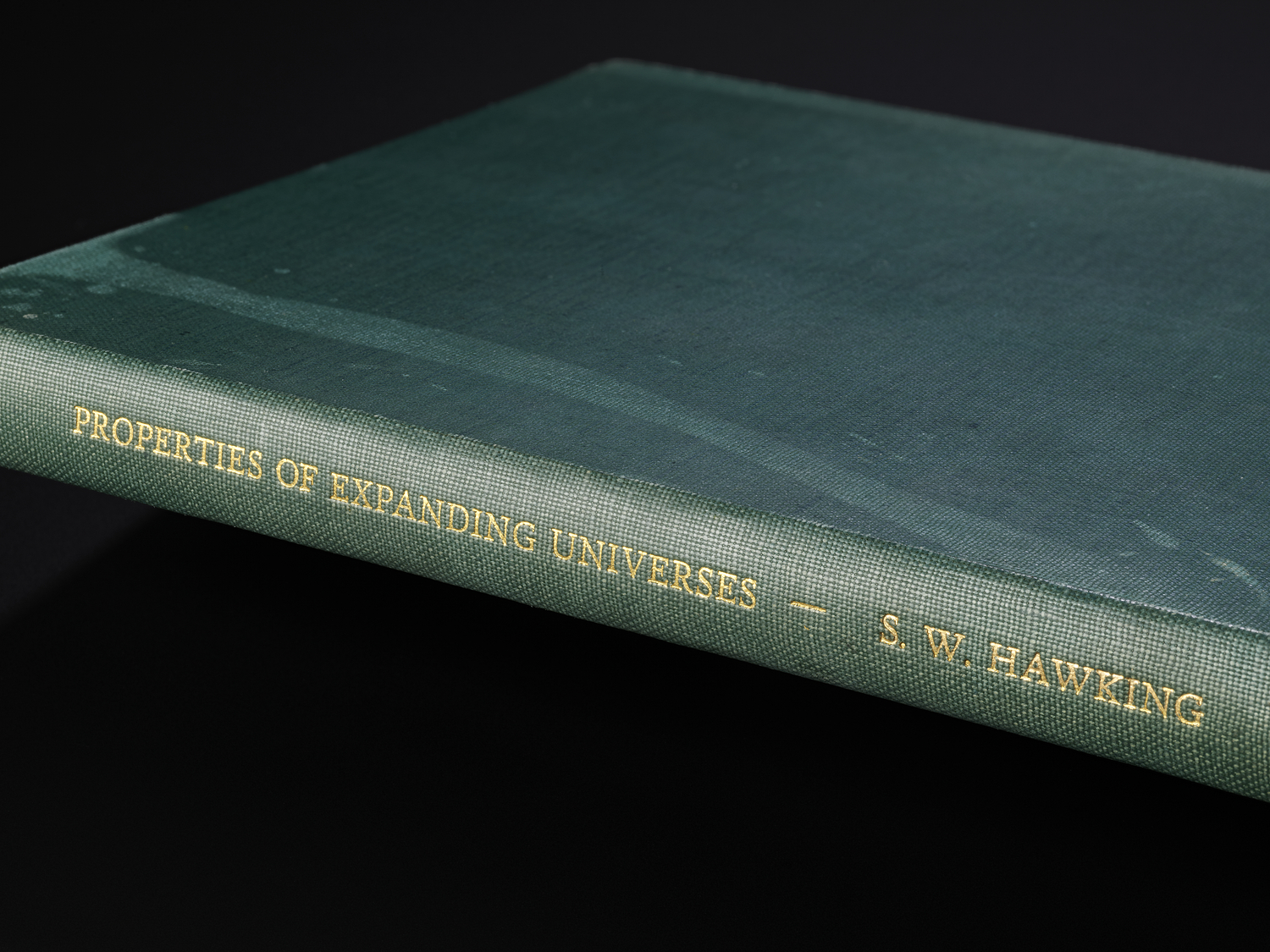

Hawking’s PhD Thesis

With its green cloth binding, this book may look somewhat underwhelming. However, this thesis is Stephen Hawking’s intellectual equivalent of the Big Bang, and all the more remarkable because he thought he might never finish writing it.

Entitled Properties of expanding universes, the thesis was typed by his new wife, Jane, submitted while Hawking was a 23-year-old graduate student at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and provides an intriguing glimpse of what was going through his mind during a time that was as difficult for him as it was exciting.

Hawking’s thesis would provide crucial support for the Big Bang theory, a pejorative name coined by the influential English astronomer Fred Hoyle, who argued that its proponents were somehow influenced by the Book of Genesis, seeking a moment of creation, and perhaps even a divine creator (Hoyle himself favoured an older and more established idea, which he had jointly put forward in 1948, known as the Steady State model, in which the universe has been around forever, and new stars are seeded in the gaps created as the universe expands).

In the concluding chapter of the thesis, the most important, Hawking applies Roger Penrose’s work on black holes to the entire universe. It enables him to show that it is possible for space-time to begin as a singularity – that space and time in our universe did have an origin.

Over the coming decades observations of the universe would verify Hawking’s work, while studies of the cosmic microwave background – the leftover echo from the Big Bang – would bury the Steady State model once and for all.

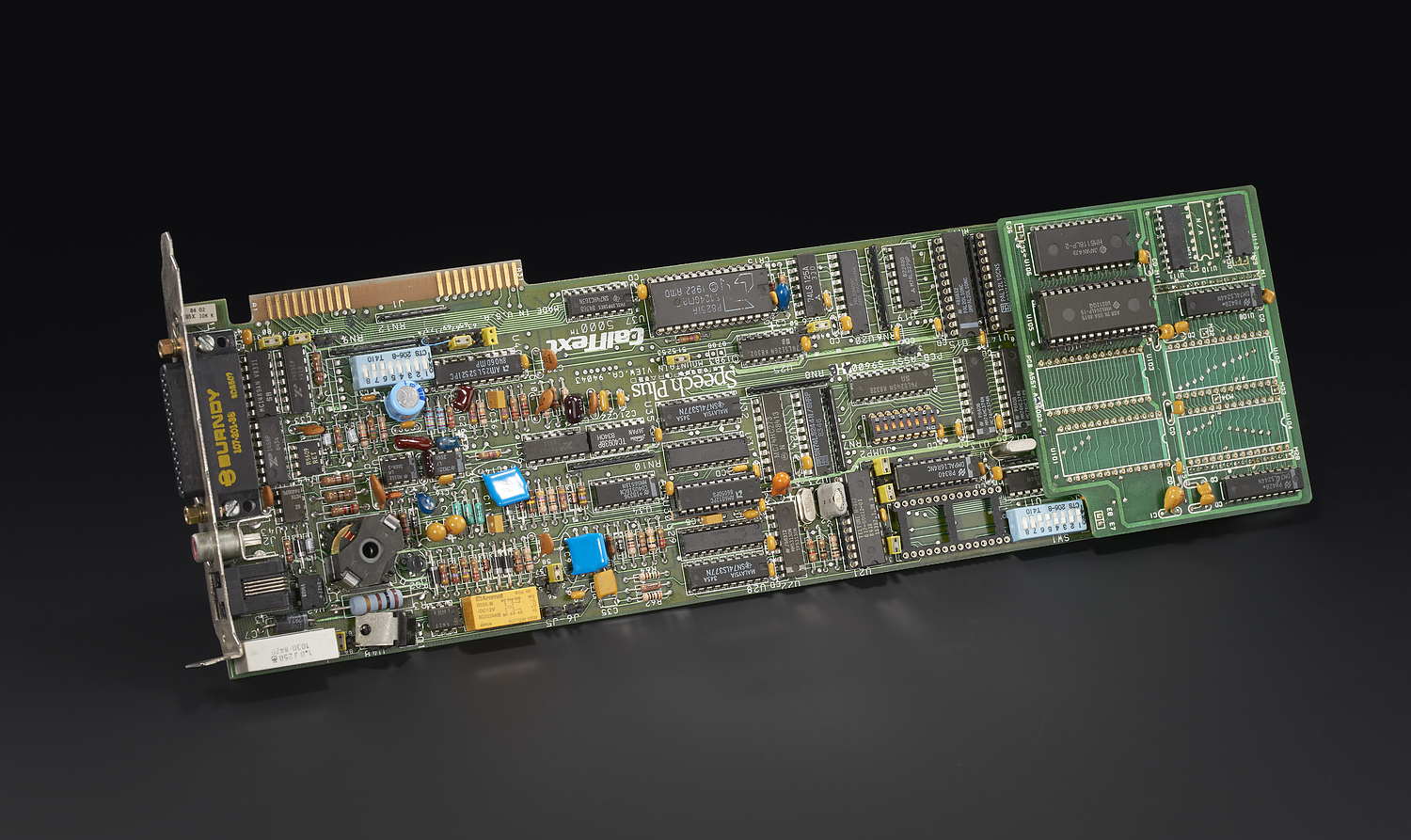

Hawking’s Voice

The story of Stephen Hawking’s voice is long, complex, and full of surprises, not least how he managed to become the greatest science communicator of his age after his natural voice was silenced.

In 1983, when he appeared on a TV science programme, his speech was already slurred and hard to decipher. Just two years later, aged 44, his voice disappeared altogether in the wake of a visit to a science conference in Geneva, when he developed pneumonia.

His motor neurone disease was beginning to paralyse the muscles of his voice box –his larynx – blocking his airway, so, to help him breathe, doctors performed a tracheotomy, which involved placing a tube into his windpipe. This left him permanently unable to speak: now, the only way he could communicate was by raising his eyebrows to select letters as they were held up on cards. The impact was devastating.

But by the time I first encountered Hawking, in California in 1988, when he was promoting A Brief History of Time,1he was using a voice synthesizer, which allowed him to speak again, in that paradoxical blend of machine and human.

Thanks to Hollywood, there was a second person to master Hawking’s voice: the actor Eddie Redmayne, who depicted him in the biopic The Theory of Everything. Hawking was so pleased with the movie he allowed the filmmakers to swap the synthetic voice they had created for his own, copyright version. ‘He offered us his voice,’ said Redmayne. ‘For me, that was the most wonderful thing.’

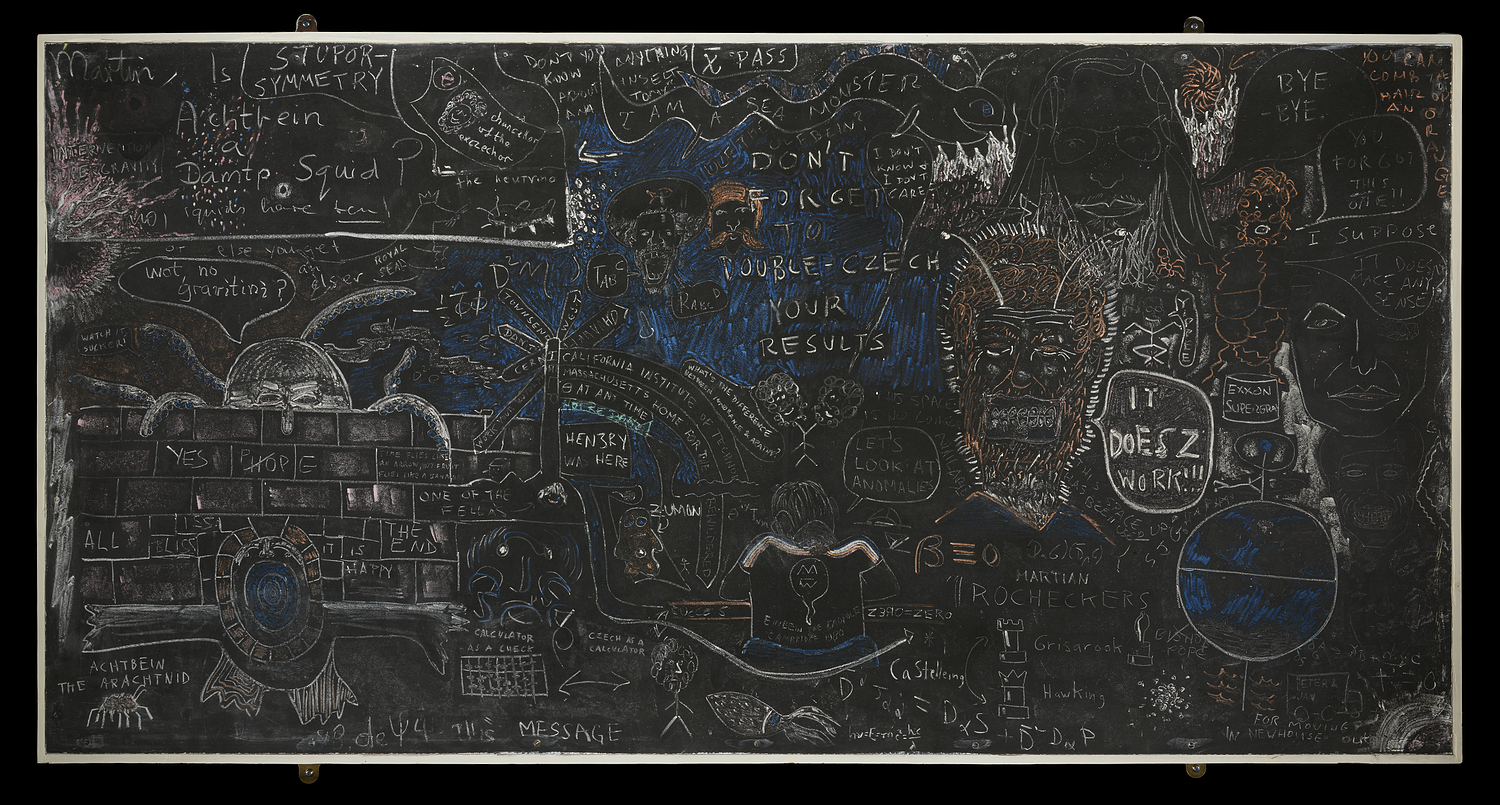

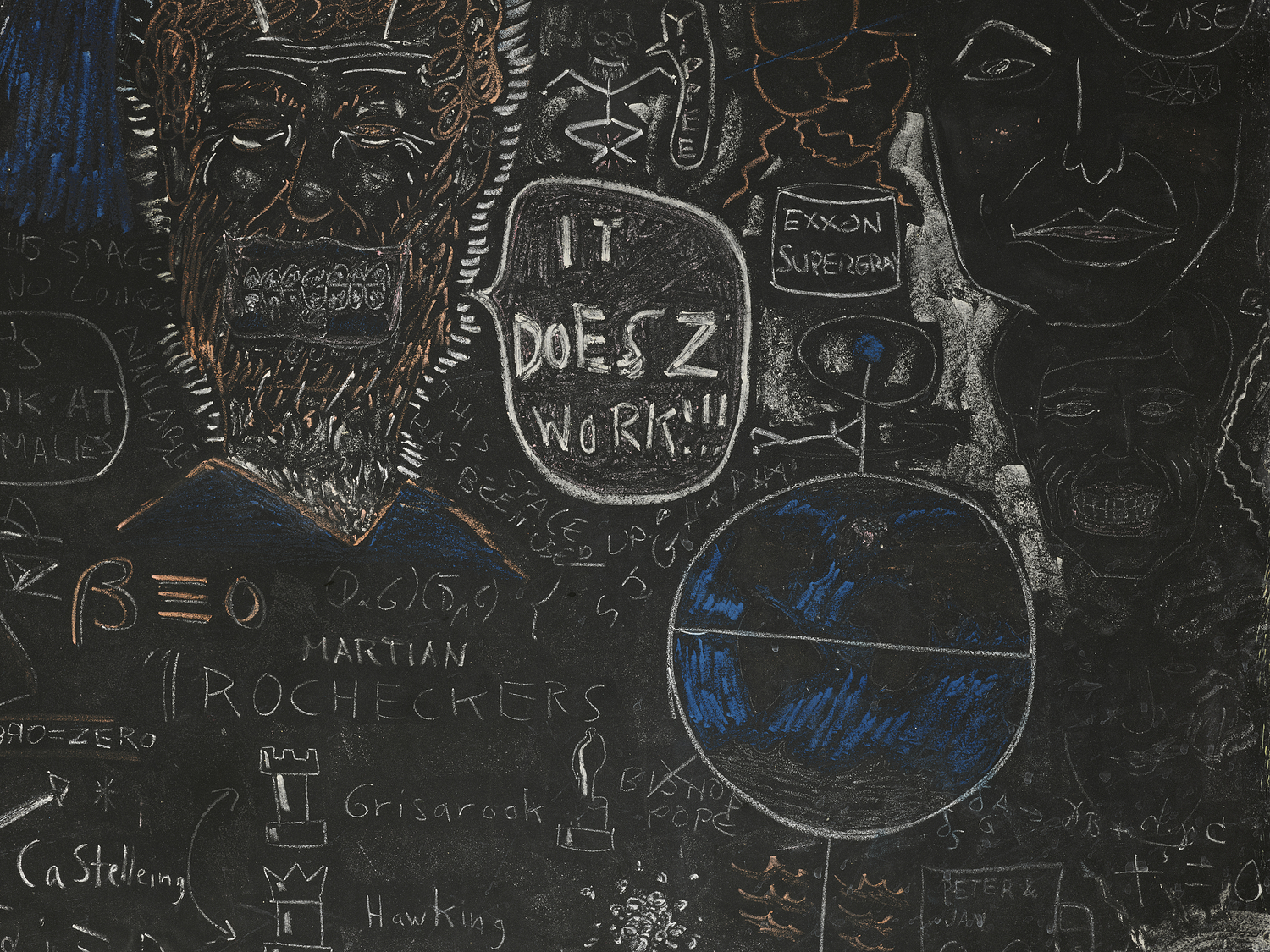

Blackboard of Scientific Doodles

As you stood in Stephen Hawking’s office, it was hard to miss this blackboard, adorned as it was, with strange doodles, cartoons, and equations.

To the uninitiated visitor, like me, the graffiti, puns, and in-jokes were mostly meaningless, but this enigmatic blackboard had a special place in Stephen Hawking’s heart.

The chalk scribbles hold a record of a meeting Hawking had organized in 1980, the Nuffield Workshop in Cambridge on Superspace and Supergravity.

Every time the delegates at the Nuffield conference hit an impasse in their discussions, they would doodle on the blackboard. Many of the jokes refer to the co-organizer of the Nuffield conference, Martin Roček, who was born in Czechoslovakia. Roček is depicted as a shaggy-bearded Martian with antennae, bellowing, “IT DOEZ WORK!!!”

Some of the scribbles are simple to decipher: ‘Czech’ refers to Martin, of course. Others show mysterious creatures, representing the group of mathematical functions or operators known as ‘Vielbein’ – vielbein being German for many-leg. Hence, Achtbein, the most promising for these ‘stupor symmetry’ theories, has eight and appears under different guises.

Where is Stephen Hawking himself? ‘I think it is rather plausible that it is Stephen is underneath the balloon,’ suggests his Cambridge colleague and fellow attendee, Gary Gibbons.

Today, the overarching message of this blackboard is that physics back in 1980 was not as advanced as Stephen Hawking had thought during that heady meeting in Cambridge. So why did he treasure it for so long? According to Roček, ‘He had a great sense of humour.’

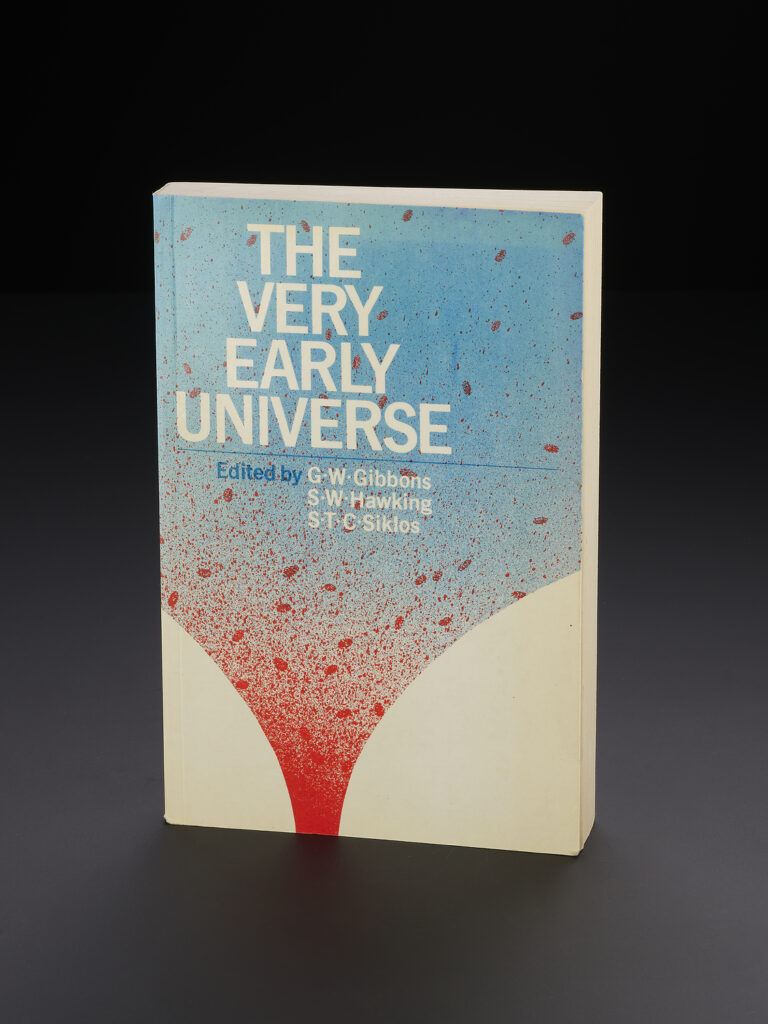

Workshop on the Very Early Universe

In the middle of Stephen Hawking’s bookshelves, above his microwave oven, is a thick book with a striking red, white and blue graphic of cosmic creation on the cover.

Inside is a record of one of the most important gatherings of modern cosmology, and it was Hawking who helped bring it about, convening the best people on the planet to work together on the hottest topic in the field.

Drily entitled The Very Early Universe, but subsequently lauded by other scientists, the book contains papers from scientists who attended a 1982 workshop held in Cambridge between 21 June and 9 July to discuss the universe’s birth, when it was less than a second old, the Big Bang model and the then brand-new theory of inflation.

While the Big Bang model suggests that the universe expanded into its current state from a primordial pinpoint of enormous density and temperature, the theory of inflation embellishes this idea by proposing that at the very beginning – at around 10 to the power of 35 seconds after the Big Bang – the rate of this expansion was exponential, so the universe ballooned by a factor of around 10 to the power of 60 – that’s a 1 with 60 zeros at the end – within a tiny fraction of a second.

Aside from putting the basic mechanics of inflation on a firmer footing, the meeting was distinguished by something else: the delegates showed how ‘primordial perturbations’ in the baby universe paved the way for the galaxies and other huge structures dotted around us in the cosmos.

This workshop was more influential than the first and is the reason why Stephen Hawking kept an inflatable beach ball in his office.

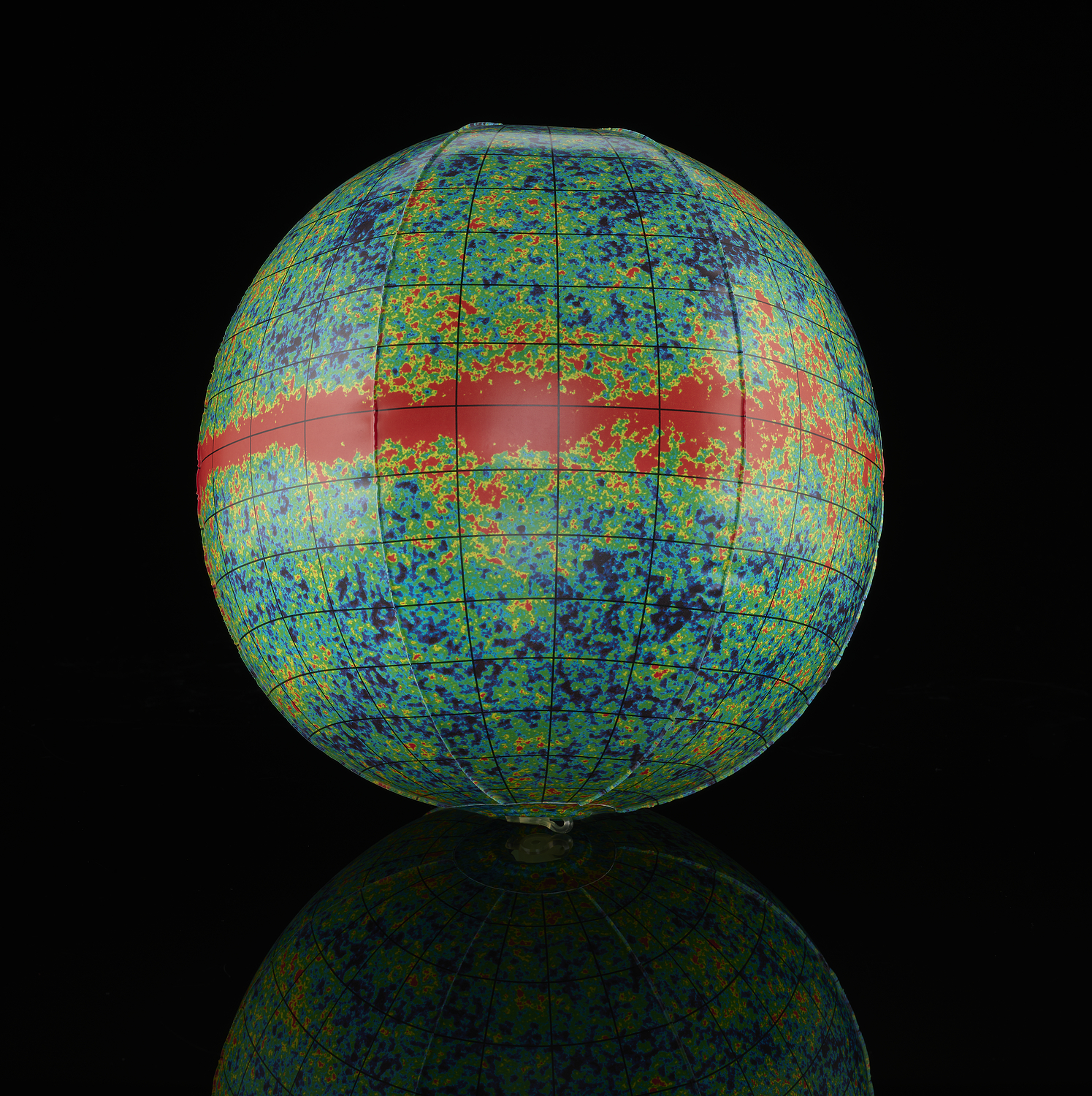

Universe on a Beach Ball

Tucked behind the computer monitor on Stephen Hawking’s desk sat this incongruous and inflatable intruder.

The ball, which measures just under a foot across is a piece of merchandise sold by the American space agency NASA. For Stephen it was something he often gave as a present to young visitors to his office, including his grandchildren.

But this throwaway curiosity also had immense significance to professors, because it celebrated one of the marvels of the modern scientific age, as it was decorated with a picture of the baby universe, an image of the afterglow of the Big Bang.

Formally called the cosmic microwave background, it was captured in an image taken in 2003 by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), a satellite named in honour of the cosmologist David Wilkinson of Princeton University.

The results from WMAP, now printed onto the beach ball, show ‘when cosmology became a precision science,’ as Stephen Hawking put it.

This little inflatable ball is not the only celebration of this milestone preserved among Stephen Hawking’s effects. There is also a small glass apple – a gift from researchers at Intel a nod to Hawking’s position as Lucasian Professor at Cambridge, a post formerly held by Sir Isaac Newton, that has been painted to evoke the cosmic microwave background, which contains what Hawking called the ‘fingerprints of creation.’

Halcyon Days

Stephen Hawking started out his academic career as an able-bodied student and became a rowing coxswain in his third year, thanks to his strong voice, light weight and daredevil attitude.

Although he could not have been aware of it at the time, his years as an undergraduate at University College, Oxford between 1959 and 1962 marked the end of the healthiest chapter of his life. It was only during his final year that he noticed he was struggling with mundane tasks, such as tying his shoelaces.

After falling down some stairs, the doctor told him to ‘lay off the beer’ and he was eventually diagnosed with motor neurone disease, after his 21st birthday in 1963.

Among the few items that he kept from his halcyon student days was his coxswain jacket. There is a note attached to say he wore the cream-coloured jacket when he was thrown into the river, an Oxbridge victory tradition that only a year later would have been inconceivable for him to perform. No wonder he kept it as a memento.

Stephen Hawking: Genius at Work is published today by DK and the Science Museum, with a foreword by the Nobelist Sir Roger Penrose. The book is available from the Science Museum shop and other bookshops.