Wireless technology and data being stored in “The Cloud” may lead you to think information is pinged around the globe via satellites. Only a very small portion is. Instant communication, like texts, phone calls and websites, is made possible by copper and fibre-optic undersea cables which carry data between countries.

97% of the internet travels through these cables. All the undersea fibre-optic cables across the world span approximately 1.2 million km (750,000 miles): combined they could wrap around Earth 30 times!

Subsea fibre-optic cables are critical infrastructures that support our global networks. They are essential for our communication, commerce, government and military functions because they securely transport messages and information. The importance of undersea cables means control or disruption of them can have political and economic implications.

Undersea cables were initially created in the late 1800s to improve the speed of the electric telegraph. The telegraph was the precursor of all current telecommunication systems. It would send information by making and breaking electrical connections in morse code. This method of communication could send messages much faster than physically transporting them.

The materials used to create telegraph cables, and the countries they connected, reflected Britain’s Imperial global power.

The first international telegraph crossed the English Channel, connecting Britain to France by cable in 1851. It was developed by brothers John and Jacob Brett and Thomas Crampton and coated in gutta percha. Gutta percha was a key material used to make the first telegraph cables. It is a natural plastic, made from the sap of trees which grow in present day Peninsular Malaysia (historically Malaya).

It was introduced to Europeans in 1656 when John Tradescant the Younger, a botanist, collector and royal gardener, brought samples back to London after one his travels to a British colony.

In 1832 Europeans learned how to fashion gutta percha into objects. It could be softened in hot water, then moulded into shape before being left to cool and harden. Gutta percha is waterproof which made it an ideal material to insulate cables. It was only supplanted by the discovery of polythene in the 1930s.

The laying of the telegraph cable between Britain and France preceded a partnership between the USA and Britain, which eventually led to the successful laying of the Transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866.

Britain and the USA revolutionised global communication with the Transatlantic telegraph cable, strengthening political ties. Telegraph cables gave countries the ability to control the flow of information, increase geopolitical influence and reinforce imperial power.

While Britain and the USA reaped their cable success, the trees which provided gutta percha veered to the edge of extinction. Making just one cable used extremely large quantities of gutta percha, and by the 1890s the cable industry was using 4 million pounds of gutta percha per year. The demand for the product was unsustainable, and so Britain formed commercial plantations in Malaya.

Britain relied on Malay knowledge for locating and extracting gutta percha from trees in the jungle. Britain used its imperial reach to secure a monopoly on manufacturing cables. The success of the cable was attributed to the West because of this control of cable manufacturing and production. The practical knowledge and important contributions of the Malay people has largely been overlooked.

While telegraphs are now obsolete, modern fibre-optic cables are laid on similar routes to the telegraph system – legacies of imperialism which continue today.

As network signals, electrical waves that carry data between devices, move between continents, they intersect with networked islands such as New Zealand, Guam, Bermuda, Puerto Rico and Cyprus. Networked islands are places utilised for running network signals.

These islands are often former colonies or territories of Britain or the USA. This meant countries could communicate with their territories more easily, and also protect the cables and the information transmitted through them from foreign interference.

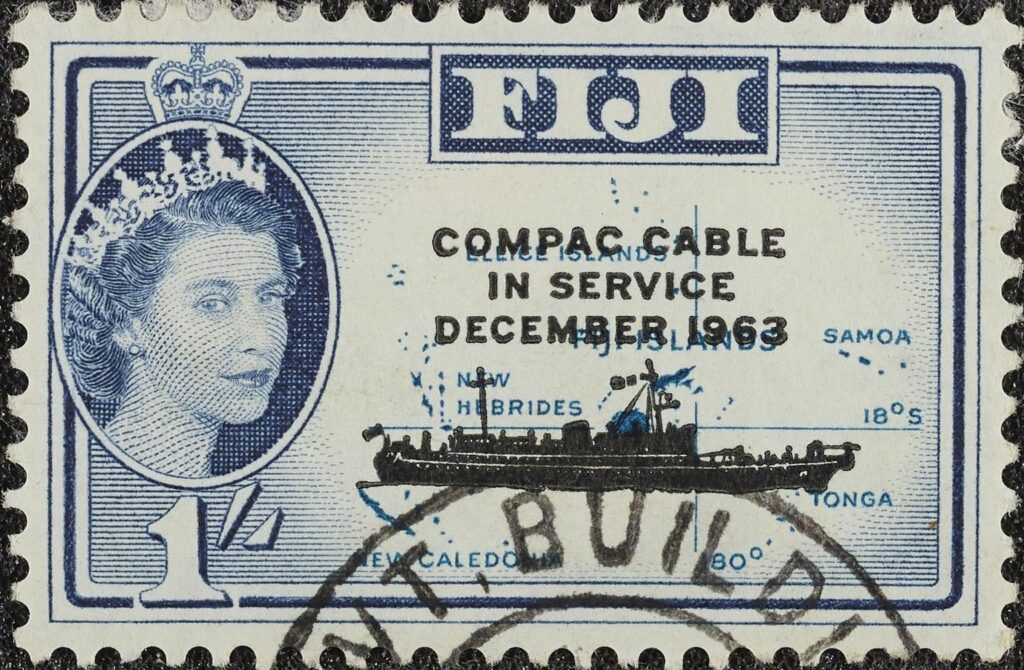

One of these previously occupied and networked islands is Fiji. The island was incorporated into Britain’s ‘all red line’, a system of cable networks linking all parts of the British Empire without ever touching foreign soil. The first cable was laid in 1902 and by the 1950-60s Fiji was established as a hub of telecommunications development.

Britain’s colonial presence in Fiji attracted private companies who wished to lay cables in the ocean and route international signals through isolated islands. The companies benefited from protection from foreign cable interference, while Britain strengthened communication throughout its empire.

From sharks biting through cables and interrupting network connections to natural disasters severing multiple cables in seconds, cable vulnerabilities take various forms.

Cables are also susceptible to intentional damage, most recently seen in the 2024 Baltic Sea submarine cable disruptions when several undersea cables were severed. This type of tampering is why telecommunication companies sought to lay cables in islands, like Fiji, which were under Western colonial occupation: it added a layer of defence from interference.

This was no longer the case in Fiji after they gained independence from Britain in 1970. A rise in political tension and coups caused telecommunications companies to abandon future cable plans there.

Fiji spent the 1990s regaining its stability and improving the economy. Now there are six fibre-optic cables in Fiji, and Google pledges to lay a further two in 2026.

The cables are part of the Pacific Connect initiative, a collaboration with several partners to increase the resilience and reliability of digital connectivity in the Pacific by connecting pacific islands to America and Japan.

The control and power exerted by nations has influenced communication technologies for many centuries, impacting the first oceanic cables to send telegraphs all the way through to the most recent undersea fibre-optic cables that bring 5G connections across the world. Private organisations now own about 99% of cables around the world, with the remaining 1% owned or owned in part by a government entity.

Today, fibre-optic cables are essential to global digital communication. Because of this, as political relationships between countries change, subsea cables can become a target. But they can also bring economic development to the places they land. With increased digital services, more people can access career opportunities or progress their skills. And undersea cables can help businesses and public sector organisations better serve and connect communities.

You can discover more stories about the history of communication technologies in the Information Age gallery at the Science Museum.