A hovercraft is a vehicle which travels on a cushion of air, enabling it to travel smoothly over both land and water, floating just above the surface. The technology behind this pioneering craft was developed by Christopher S. Cockerell, an electronics engineer who had an interest in boat building. Noticing that a lot of power was wasted by traditional motorboats as they push through the water, he began experimenting with the idea of creating a film of air under the vessel to reduce resistance and improve efficiency.

His key breakthrough came with some quite unassuming materials, two coffee tins! By stacking two cans of slightly different sizes inside each other and forcing a jet of air through the gap between the two, he created a more focused and powerful thrust. Cockerell then scaled up this technology for the hovercraft, using a ring of air around the craft’s circumference to create a more successful air cushion system, enabling it to hover.

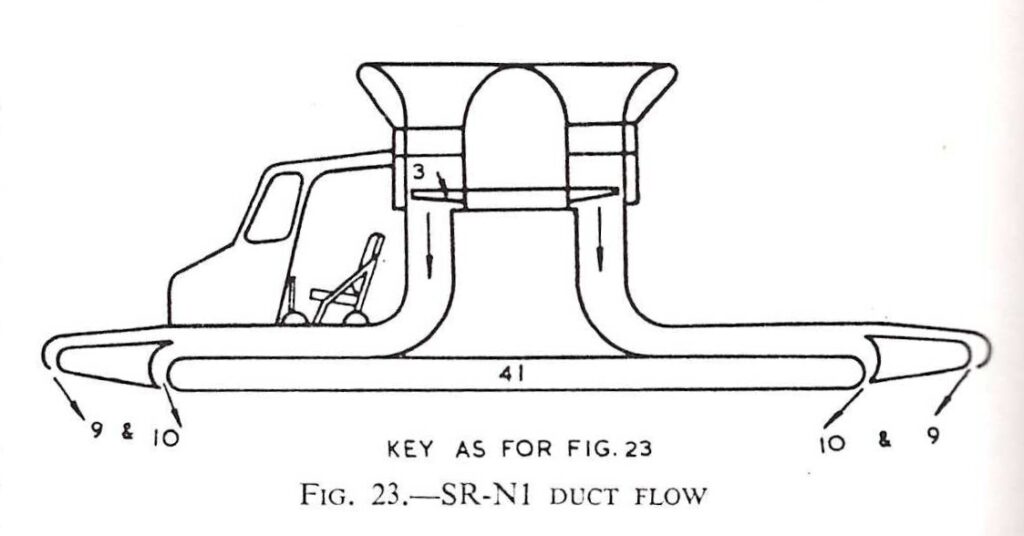

This illustration demonstrates the air flow used within the SR-N1. The air is drawn in through the large central funnel in the centre of the hovercraft using a four bladed fan. The SR-N1 uses a “double curtain system”, producing two rings of air underneath the hovercraft, rather than just one. Only two-thirds of the air drawn in through the central funnel is used to create the air cushion and the rest is expelled through the ducts which are located alongside the cockpit, parallel to the floor, to propel and steer the hovercraft.

This technology was game-changing and enabled the successful creation and maintenance of an air cushion below a craft. However, while the SR-N1 is widely publicised as the world’s first hovercraft, it is important to note that variations of this technology and attempts to develop hovercraft had existed for years in countries such as America, Austria, Finland and the Soviet Union.

Despite the eventual uptake of Cockerell’s hovercraft technology, he struggled to build interest among commercial industry or government departments. He pitched his model hovercraft to multiple organisations but because it sat between two previously defined technologies – ships and aircraft – there was limited interest. Shipbuilding firms said it was not a ship and that he should present it to aircraft manufacturers, while aircraft companies said it was also not an aircraft and that he should talk to the shipbuilders. Although the Ministry of Supply were interested, they classified this development as ‘secret’ for a few years.

Cockerell’s research had been declassified by 1958 and in January of that year a new company, Hovercraft Development Limited, was established using funding from the National Research Development Council (NRDC) with Cockerell in place as the technical director.

Saunders-Roe, an aerospace and marine engineering company, had carried out a feasibility study into the hovercraft in 1957 (on request of the Ministry of Supply). Due to the success of this report they became involved with Hovercraft Development Limited and together began programme of work, headed up by chief designer Richard Stanton-Jones, which led to the development of the SR-N1. After successful tests of model hovercraft using water tanks, the full-scale SR-N1 was built.

The hovercraft took its first public flight on the 11 June 1959 at the Saunders-Roe Columbine Works in East Cowes on the Isle of Wight. Here, surrounded by press and photographers, it hovered above the ground and moved around, floating on a cushion of air. It was then taken out to Osborne Bay, in front of the public, where the craft was towed out into the water and tested for the first time.

As noted by the craft’s pilot, Lieutenant Commander Peter Lamb, test pilot for Saunders-Roe, it produced a surprising amount of spray, but the initial water tests were successful and visibility improved once they were underway.

Within a few days of testing, Lamb had adjusted to the spray and controls and the craft was able to achieve its predicted speed of 25 knots (around 28mph). After crossing the Solent (between the Isle of Wight and mainland England) later in June 1959, by July the SR-N1 was ready to undertake its biggest journey yet.

On 25 July 1959, the centenary of the first airplane flight across the English Channel by Louis Blériot, the SR-N1 successfully crossed the channel from Calais to Dover. It was piloted by Peter Lamb with Christopher Cockerell as one of the other two crew members, with the journey lasting just over two hours.

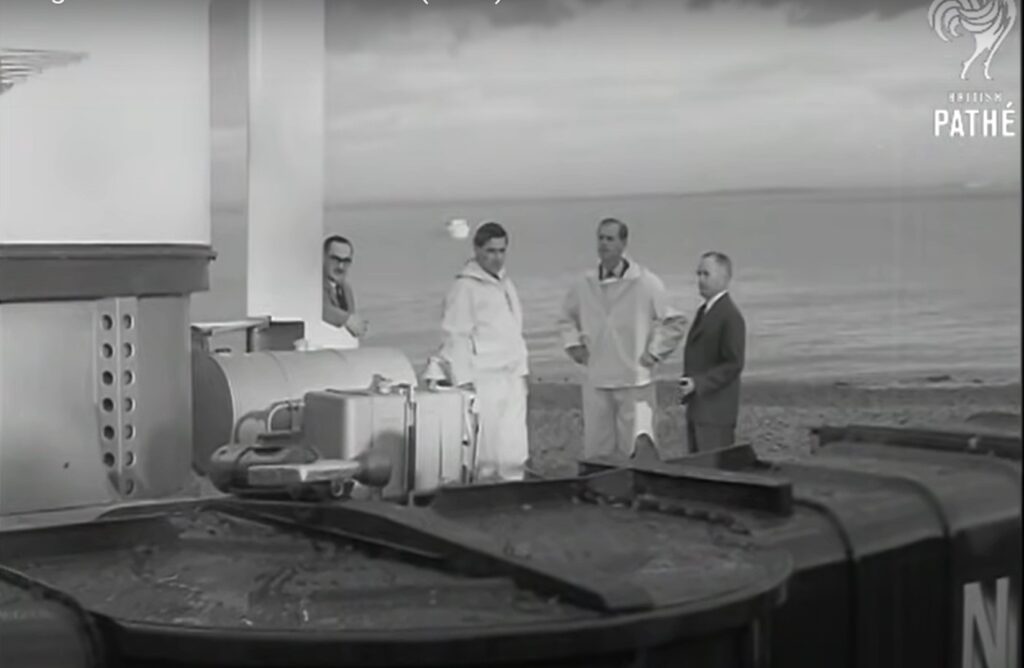

On 18 December 1959, the SR-N1 hovercraft had a much more famous pilot for the day, H.R.H. Prince Philip. He was taken out in the hovercraft to experience it as a passenger before being passed the controls. He manoeuvred the craft through the choppy waters of Castle Point and out into undisturbed sea before the Chief test pilot, Peter Lamb, resumed controls and returned them to Osborne Bay.

Upon assessment of the craft after return to the harbour at East Cowes, a dent in the false bow was observed, likely caused by impact with the sea during the flight. This was henceforth known as the “Royal dent” and was agreed to not be repaired straight away as a memento.

After the success of the SR-N1 in the late 1950s, hovercrafts were seen as the future of transportation and significant money, time and effort was put into the development of this technology by a variety of companies. While not essential for function, the addition of flexible skirts, patented by Latimer-Needham in 1962, was a big step in enabling the furthering of this technology, as these allowed hovercraft to traverse more obstacles on land and sea and enabled manufacturing in production line fashion.

In 1966, the British Hovercraft Corporation (BHC) was formed, combining three key hovercraft organisations, Westland, Vickers and NRDC. In the same year, Seaspeed (British Rail Hovercraft Ltd.) became the first to offer scheduled hovercraft services, initially running from Southampton to Cowes and adding cross-channel travel (Dover to Boulogne) in 1969.

By 1968 around 20 different types of full-scale practical hovercraft had been built and designed in Britain, with some running regular trips across the channel, carrying cars and passengers. These trips were significantly faster than the ferry, cutting the 90 minute journey from Calais to Dover, to 30 minutes. However, rising fuel costs, the opening of the Channel Tunnel and issues with the longevity of hovercraft engines due to saltwater intake meant that such commercial hovercraft technology became no longer viable. The SR-N4, which ran a cross-channel service from 1968, took its last trip in 2000.

The SR-N1 hovercraft itself was offered to the Science Museum in 1964 by Westland Aircraft Ltd (who had taken over Saunders-Roe). Despite the desire to acquire this historic object, there were queries about where best to store it given the museum’s storage constraints at the time. Therefore, following the official presentation of the SR-N1 to the Science Museum in 1968, it was loaned to and exhibited at the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu. The hovercraft arrived in a rather unorthodox fashion, travelling from Cowes across the Solent and up the river to The National Motor Museum under its own steam as a working vehicle. The SR-N1 was on display outside at Beaulieu for around three years and returned to the Science Museum in 1971.

Upon agreement with the museum, work was undertaken in the 1970s by the British Hovercraft Corporation (BHC) to restore the hovercraft to suitable condition for static display. The photograph below was taken in 1980 when the SR-N1 was delivered back to the Science Museum Group’s site in Wroughton (now known as the Science and Innovation Park), where it still resides. The image shows some of the staff from BHC who worked on this project alongside others integral to the creation of the SR-N1.

There is only one year-round commercially functioning hovercraft service today. The Isle of Wight Hovercraft runs a regular passenger service between Ryde, on the island, and Southsea in Portsmouth, with the journey taking only 10 minutes, approximately half the time it takes via ferry. This service offers the opportunity to experience the technology which so captured imaginations in the mid-late 20th century, flying across the Solent as the SR-N1 did 65 years ago.