Human beings are complex. Whilst we are individuals, we are social creatures. There are certain behaviours that we perform which are universal and reinforce this social nature. Taking selfies is definitely one of these.

The term selfie is credited to Australian Nathan Hope. In 2002 he posted a photo from his birthday on social media and captioned it ‘…sorry about the focus, it was a selfie’. It became a colloquial term, spreading out across the world.

In 2013, ‘selfie’ was officially added to the Oxford Dictionary – ‘a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website’.

The ubiquity of selfies amongst generations, cultures, nations, make it a social phenomenon. The idea that it might be narcissistic has been widely disproven in academic research. In fact, the act of selfie making is a social ritual: the image is taken of oneself by oneself, ultimately to be shared.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a selfie is a perfect example of how we make our own identity: a single image can tell multiple, complex things about a person to peers, friends, family, and social group. Selfies empower us to promote who we are and to control how people see us. The content and style tell of our interests, signifies our similarities and affinities. In this way, the act of taking (and sharing) a selfie is to create a sense of belonging.

University College London (UCL) found selfies work as pieces in a puzzle, so that a series of selfies combine to convey the multiplicity of a personality in different social settings. The act of taking the selfie and using this to tell a story about oneself in relation to others makes it a social activity.

UCL even identified multiple selfie ‘genres’, which have become apparent in relation to different nationalities. For school children in England, there are three main genres: ‘classic’ selfies with just one person, ‘groupies’ with friends and ‘uglies’ depicting people at unattractive angles. Meanwhile in rural China, it is popular for women to add cartoon filters over their selfies.

Despite selfies seeming relatively a new thing, they have actually been a part of the photographic canon since photography was invented, and before this too. These ‘original’ selfies were done for the same reasons: self-expression, to tell a story about the taker, to signify and reinforce their identity, and to share these images with others in their social group, for approval.

‘Selfie’ is a hypocorism, a shortening of a name to show affection, of self-portrait. The earliest selfie to be taken with a camera predates the term by 175 years. This selfie is attributed to Robert Cornelius in 1839 and on the back of it is written ‘The first light picture ever taken’. Quite a claim. But in some ways it is this description, not the ‘classic’ style, that makes it a selfie: it is posturing. Cornelius captured himself being the first to do something and then shared it for ‘likes’ (or the equivalent acclaim in 1839). For unspoken in this image is the audience who viewed it.

The Science Museum Group Collection holds many selfies from long before the term became official. All of these follow certain tropes which make them worthy of posting to ‘The Grid’.

Lady Hawarden conveys many messages about herself to the viewer with this photograph. Her direct, defiant look, her voluminous dress which takes up almost the whole frame, her skill at taking a striking self-image: all of this promotes a powerful standing through an image, made by a woman, in a time when society had little space for women.

Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II of Jaipur overtly utilises the principles of iconography (which originated in fine art) in his selfie. That is, he used carefully selected objects and deployed them as symbols – the mirror, beads, pot of oil – to create a persona: a Shaivite (a worshiper of Shiva).

Singh’s works were the first examples of Indian self-portraiture in photography. Singh knew how to manipulate the selfie format, long before we discovered hacks for the perfect selfie in natural lighting.

Brassaï was a Hungarian-French photographer, famous for capturing the gritty nightlife of Paris in the 1930s. This selfie was featured on the cover of his book of printed photographs ‘Camera in Paris’, 1949.

The book has little text, but with this cover image by way of introduction, there is little more to be said: here is Brassaï set up to photograph the streets of Paris at night, and he is very much at home in this setting – a part of the Boulevard Saint-Jacques.

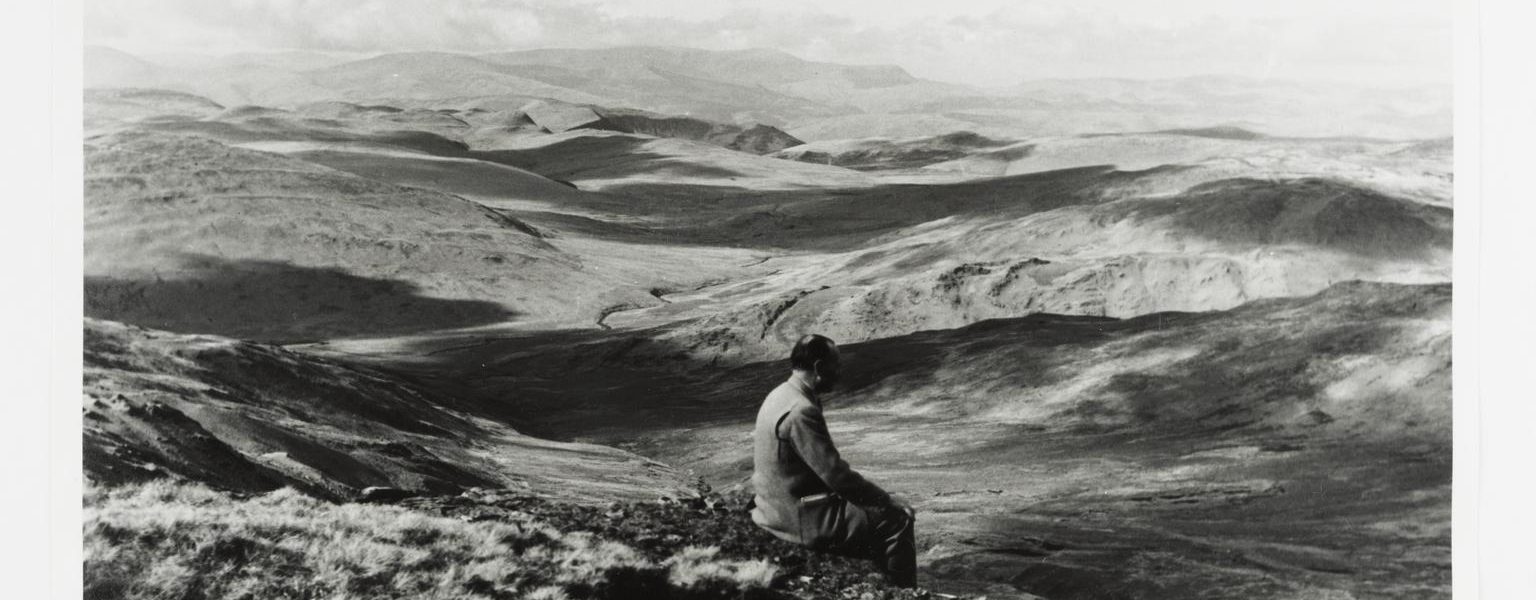

In this selfie by J. Allan, we can see Allan peaceful in beautiful countryside; demonstrating both his hobby of walking and impressive photographic skill, creating such clear focus on a distant horizon.

If Allan had Instagram now, would it be too farfetched to assume his followers would be countryside enthusiasts? The title even speaks to the act of making one’s identity in the selfie: ‘the author’.

Meanwhile Cecil Beaton, with his cheeky grin, conveys his humorous side in his self-portrait. Is this showcasing a holiday snap? If so, the format is fitting with estimates that adults take an average of 14 selfies a day whilst on vacation.

We also hold a series of photographs taken as part of the Time to Reflect UNICEF Project in 2008, which raised £35,000 at the time. These images were taken in a photobooth by each person and orchestrated by Alistair Morrison. Here the selfie is used to showcase the uniqueness of the celebrity personalities involved. Yet again there are the same signifiers of the selfie: with the celebrities taking their own image to showcase their affiliation and support of UNICEF, then sharing it.

Selfies are a social behaviour and as demonstrated by our collection, they have been important to us long before the term ‘selfie’ existed.

The rapid ubiquity with which selfies became a mainstay in our lives only further proves their social importance. Whilst the popular phrase, ‘if you don’t take a photo, did it even happen?’, may not be true, selfies do help define who we are and a sense of belonging.