The longest running seed experiment is 142 years old. Started by botanist William James Beal back in 1879, the experiment was prompted by farmers asking Beal whether weeds would keep coming back, even if they patiently kept weeding the same spot.

It involved bottling 20 glass bottles containing a seedy-sand mix of 21 different plant varieties local to Michigan State, USA, and burying them on the Michigan State University Campus. The plan was to dig up a bottle every 5 years to see which seeds would germinate and find out how long seeds could last dormant before being brought back to life.

This experiment was intended to last far beyond Beal’s lifetime and, as it was passed on to new guardians, the time between bottle retrieval was lengthened to allow the experiment to last longer. Currently, the bottles are dug up every 20 years.

The scientist Frank Telewski, one of the experiment’s current guardians, dug up the latest bottle in April 2021. Acting like treasure hunters, Telewski and his fellow guardians located it with an old map, dug it up under the cover of darkness. They needed to do this stealthily so the bottles that remained buried wouldn’t get any sunlight.

Whilst the experiment was prompted by the desire to prevent weeds, today it takes on new – almost opposite – significance. Instead of finding ways to stop plants from growing back, we now need to study and bury seeds to prevent extinction and to maintain biodiversity.

Seeds, like animals, are facing the negative impacts of climate change. It is estimated that three seed producing plants have gone extinct each year since 1900. This is 500 times faster than would be expected. And it is reported that 40% of plants are at risk from extinction.

Beal’s experiment is a precursor for our current day seed banks, where seeds ‘are stored to preserve genetic diversity for the future’ (Observatree), a kind of insurance policy against climate change. These banks are a little more complex than glass bottles buried underground; they are flood, bomb, and radiation-proof vaults!

So, what are the impacts of climate change on seeds?

Climate change changes plant phenology (meaning plants flower and produce seeds out of sync with when insects are ready to pollinate them), muddles their adaptability to extreme weather patterns and purges natural seed banks.

Whilst, for some seed producing plants, progressively warmer climates have resulted in new species thriving – like spinach and tea, it is expected that extinction rates will be out of proportion to these new varieties.

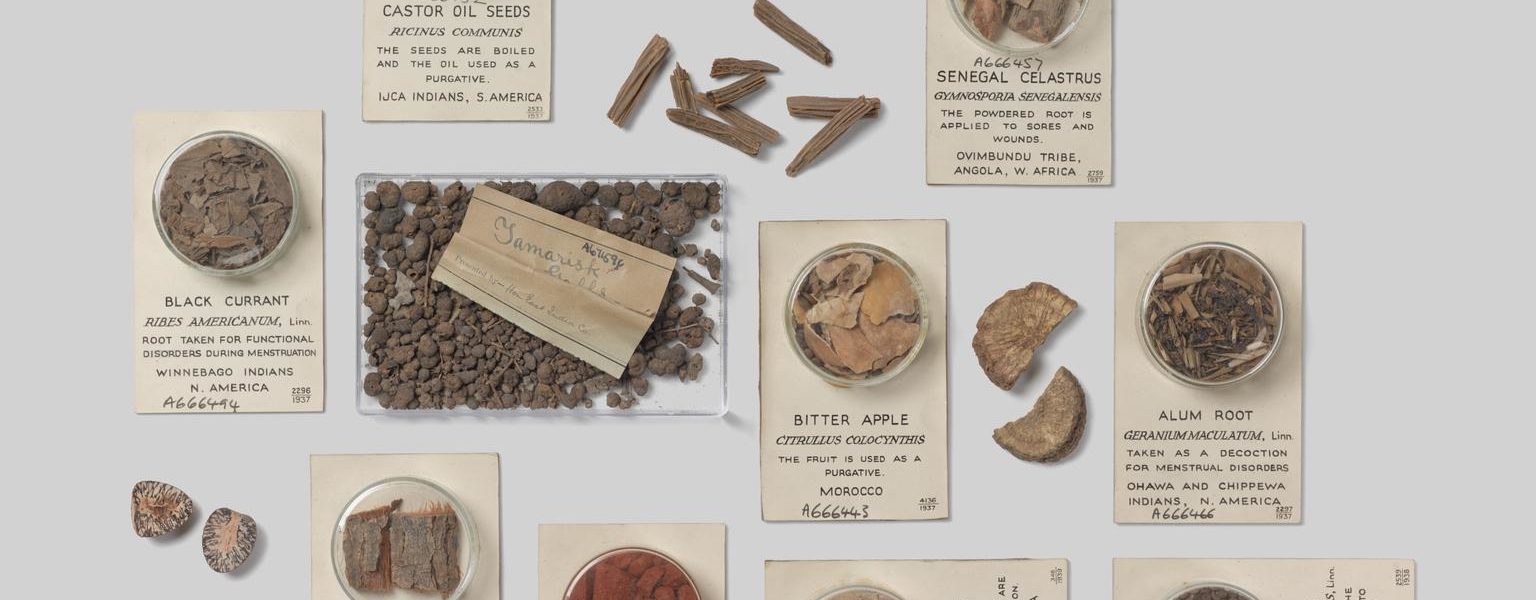

This is worrying because seeds are hugely important to human life and livelihoods. They are at the core of our diets, in our medicines and even cleaning products.

Seeds have also played a key role in society throughout history; as charms, weights and symbols of faith.

There are 7,039 known species of plant and fungi available for us to eat, yet amazingly, a mere 15 crop plants contribute to a massive 90% of human energy intake! Such lack of diversity in our diet means more risk. In other words, we’re putting all our eggs in the same basket. We need to seek variety in our diet to encourage diversity in plant life.

This got me thinking – what variety of seeds are stored in the Science Museum Group Collection? And can any of these compete with the Beal experiment in terms of age?

In our collection, we have European sunflower seeds and Sudanese cherry seeds, both dating from possibly as far back as 1900. Both of these seeds are still popular and flourishing in some varieties, yet some have been lost.

We have Egyptian oat seeds from 1870 (the oldest oat grains are thought to have come from Egypt). Whilst oat could also be perceived as a common seed, some varieties like Radnorshire Sprig and Hen Gardie (which were once common in Wales) have not been grown for 50 years (an experiment to reintroduce these is currently underway – which is very exciting).

We have an entada scandens seed, which washed up on the Northwest Irish coast, estimated to be 112 years old and another which is 172 years old. These seeds were fairly common in the UK, despite not being indigenous. They washed up on our shores from the gulf stream, and would be used by British people in the 1700s as charms for childbirth and to avert drowning.

We also have black poppy seeds from New Zealand, dated 1866. A bottle of cudweed seeds and flowers from 1851 which were used by indigenous peoples in North America for their medicinal qualities. Cudweed can also be found in the UK, although only in small amounts – it was brought back in 1994 after it went extinct in the wild. And its status remains ‘Critically Endangered’ and ‘Globally Threatened’.

Possibly our oldest seed is a large green seed pod called cassia fistula, originally from Southeast Asia. Popular in East London from 1830 until about 1920, these seeds were used for their medical properties to ease constipation.

But it is important to remind ourselves that these seeds, like the cassia fistula, are emblematic of the history of colonialism. That a plant from Southeast Asia could wind up in East London as a mainstay of apothecary medicine in 1830 is a demonstration of unequal colonial extraction; the unfair exploitation of colonised peoples by the taking of their valuable resources.

The Beal experiment has now recruited guardians from diverse backgrounds in the hope of bringing broader perspectives to this very long experiment.

To revive the latest cohort of Beal seeds, Telewski and his team have been using different methods to kick start germination. This includes a cold treatment, smoke baths, plant growth hormones as well as roughing the edges of the seeds. From the current Beal bounty, 11 seeds have successfully germinated!

The current guardians have also decided to bury their own seeds, this time in 40 bottles, allowing us to return to this experiment in at least 400 years from now!