No recent year has confounded climate scientists’ short term predictive capabilities more than 2023 has, according to Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City.

It takes time to gather all the information on how the planet fared each year and, now the data are in, it turned out to be 0.2C warmer than the previous record year (which was 2016) and 0.3C warmer than 2022.

The size of the record margin and the size of the year-on-year change have both raised eyebrows. As Schmidt wrote in a recent issue of Nature, ‘We need answers for why 2023 turned out to be the warmest year in possibly the past 100,000 years. And we need them quickly.’

For the best part of the past year, mean land and sea surface temperatures have overshot previous records each month by up to 0.5 °C. That does not sound much but, to a climatologist like Gavin Schmidt, it is ‘a huge margin at the planetary scale.’

The best-known climate models, which you can explore in the Science Museum’s latest gallery, Energy Revolution: The Adani Green Energy Gallery, are honed on historic data and use billions of equations, vast amounts of data and supercomputers to predict the future.

These models do show that 2023 follows the general warming trend models predict from rising greenhouse-gas emissions, he said, broadly lying within the range of predictions.

The key issue is, according to Schmidt, whether the unanticipated pattern of anomalies seen last year, and in a range of data sets, are the harbinger of an accelerated warming trend.

This can be seen when using another kind of climate model to make shorter term predictions over the following year. Most harness statistical methods where past global temperatures, data about climate patterns (notably the El Niño Southern Oscillation, see below) at the end of the previous year, and so on are used to predict next year’s global temperature. Other groups harness complex simulations which use the observed conditions as their starting values.

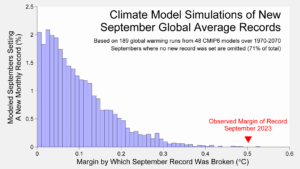

However, none of these models captured the size of the 2023 high temperature anomaly: scientists know what typical variability looks like but the high temperatures last year fell well outside the historic precedents of climate fluctuations.

The sudden spikes ‘greatly exceed’ predictions made by the short-term statistical climate models that rely on past observations, said Schmidt. As the financial sector likes to say, past performance is no guarantee of future results, but the size of the anomalies is troubling. ’It is humbling to the point of worrying whether the anomalous temperatures seen last year are a ‘blip’, or ‘something systematic’’, he said.

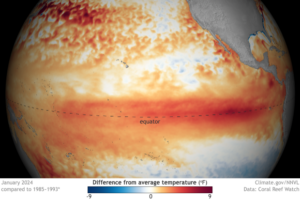

One major influence on global climate is ENSO, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a recurring climate pattern which can either temporarily cool the planet, when it goes through a phase called La Niña, or temporarily warm it, when it is in the El Niño phase, as the Earth was this past winter.

Early last year saw the end of a three-year period of La Niña, and based on earlier precedents when similar conditions prevailed, Schmidt and others had put the odds of 2023 turning out to be a record warm year at just one in five at the beginning of that year.

But the 2023 temperature anomalies measured by an array of weather stations and satellites has not only been much larger than expected, but also appeared several months before the onset of the warming El Niño: last March, sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic Ocean began to shoot up. ‘Bonkers’ warming records were set in August and September, said Schmidt.

As the El Niño fades, the expectation would be that anomalies will dissipate first in the ocean and then and then elsewhere. ‘But that [relative cooling] doesn’t seem to be quite happening yet,’ he said, as 2024 is off to a record warm start. ‘If we’re still breaking records in August, that will be that will be quite ominous, right?’

Various explanations have put forward for the anomalies. Could it have something to do with the fallout from the January 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcanic eruption in Tonga, which had both cooling effects from aerosols and warming ones from stratospheric water vapour?

Or perhaps it was the rise in the Sun’s activity in the run-up to a predicted solar maximum?

Or was it something to do with the fallout of the 2020 regulations that made the shipping industry reduce emissions of sulphur compounds? Though this makes the industry cleaner, it also cuts the impact of those compounds on clouds, which have an overall cooling effect.

‘What blows me away is how confident the people are that they know the answer without having done any work to demonstrate it,’ said Schmidt, adding that, when taken together (so far), these factors explain a few hundredths of a degree in warming, which falls far short of the divergence between expected and observed annual mean temperatures in 2023 of about 0.2 °C. ’Because we don’t have a great answer for what happened 2023 then anything is on the table.’

The models need more and more timely data to make sense of this anomaly, he says. But if the anomaly persists the world’s climate could be in uncharted territory.

Tamsin Edwards, a professor at King’s College London, who specializes in looking at the uncertainties of climate predictions, said the anomalies are ‘sobering’ but added that she would only start to worry if they persist until the end of this year. ‘I am in the watch and wait camp: I think we’ll know a lot more by the end of this year.’

Tim Osborn, Professor of Climate Science & Director of Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia added that, in terms of how far 2023 stands out from previous records or previous years, the anomaly is clearer in the global sea surface temperature than it is in the global land temperatures. And, of course, the oceans have much more heat capacity, and thus are the engines of the global climate system.

He agreed with Gavin Schmidt that, in terms of changes seen in the global climate since preindustrial times, the temperatures seen this year and last still lie within the range of long-term warming projections but are unusual in the rate of change, the variability, over the course of a single year.

If anything is missing from current models, it is not understanding of the physics, he said, but that the data fed into the models is insufficient, such as our understanding of how aerosols in the atmosphere have changed in the last few years.

The statistical models used for the one-year-ahead predictions might underestimate how much the climate can fluctuate over these short time scales, he said. ‘The concern would be if it’s part of an acceleration in the global warming rate, and we’re just seeing it so far with a one-year spike.’

The cause of the anomalies will be discussed over the next few months at conferences, such as the American Geophysical Union, and various workshops, said Schmidt. ‘I’m moderately confident that if you ask me about this in a year’s time, we’ll have better answers.’