The Women’s Health Movement was a social and political movement in the 1960s and 1970s with the goal to improve healthcare for all women. It emerged from the second wave of feminism, where women were fighting and protesting for legal and social equality. A major concern of the Women’s Health movement was expanding reproductive rights, such as access to contraception and abortion, and changing childbirth practises.

Self-help groups were developed and became a crucial way for women to gain knowledge about their own bodies so that they could take control of their health. Women formed grassroot organisations called consciousness-raising groups to raise awareness of the inequalities and health issues they faced.

‘Women in health’ series for the east london project

These three posters were a mini-series created with the East London Health Project and the Women’s Health Information Collective in the late 1970s. The East London Health Project was launched in 1978 to raise public awareness around what campaigners saw as damaging cuts to the National Health Service in their area. Who were the Women’s Health Information Collective and how did your collaboration with them come about?

Loraine: The East London Health Project steering group felt we should address some of the health issues that particularly affect women and put me in touch with the Women’s Health Information Collective. I visited this group of health professionals where they brainstormed the issues that they felt to be most pertinent at the time and arrived at the three topics represented in this series of posters.

These posters tackle a wide range of themes: complex feelings about the contraceptive pill, the actions women can take to stand up for their health, and how the stress of being the perfect women can affect women’s health. The posters are all visually linked by featuring the same model. Who was this woman?

Loraine: At the time I was teaching on the Art and Environment course at the Open University. The woman in the posters was a student I met during one of the summer schools. She was sympathetic to the project and agreed to let me photograph her for the posters.

I felt that she was someone to whom other women might readily relate, though in retrospect more diversity in the representation would have been desirable.

How did gender and gender politics shape your thinking and artwork?

Loraine: The second wave of feminism in the seventies was an important period of growth for women and included social, economic, and political equality, reproductive rights, and challenges to traditional gender roles.

At the time, feminist consciousness permeated political thinking on the Left, particularly where women were involved. It therefore made sense to ensure that issues affecting women were foregrounded, despite the fact that in practice there was still a long way to go with the feminist agenda.

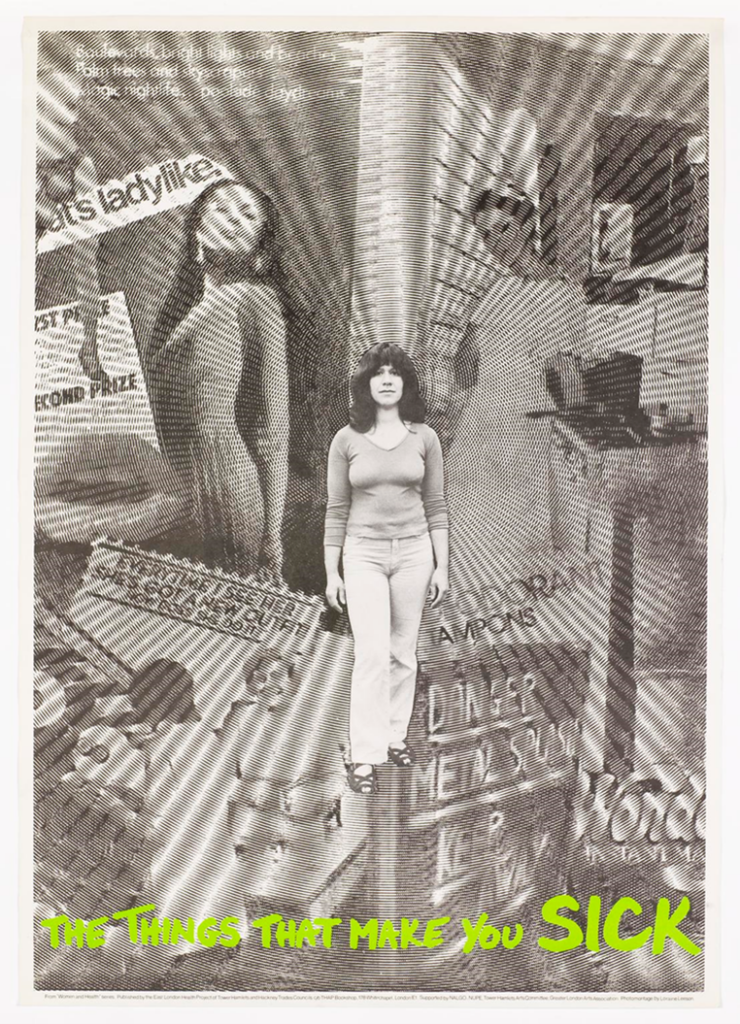

‘The things that make you sick’

This poster features an eclectic range of images: lips, a woman in a kitchen, advertisements for ‘deodorant tampons’, a danger sign. What was the inspiration behind this poster and how does it link to health?

Loraine: The energy and commitment of the Women’s Health Information Collective was my inspiration for all these posters. The group felt strongly that many of the medical issues affecting women resulted from the pressures to conform to a social stereotype. This included aspiring to a particular body type, the necessity of paid employment at the same time as bringing up children and being the perfect wife – also using the products manufacturers were promoting to make us feel we could realise these aims.

The background images in the poster, including the words, are taken from printed media like magazines. Much of this awareness had been generated through women’s consciousness-raising groups.

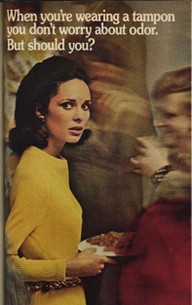

The example of deodorant tampons

Deodorant tampons feature as one of ‘The Things That Make Us Sick’ in Loraine Leeson’s poster. Deodorant powders for use with menstrual pads were first introduced in the 1930s. Scented tampons were introduced in the mid-1940s, playing on fears that even wearing ‘internal protection’ wouldn’t prevent odours revealing you were menstruating.

Playtex launched deodorant tampons in 1971, even though menstrual blood doesn’t have an odour until it is exposed to the air (which doesn’t happen until a tampon is removed.) These were advertised as having a ‘fresh, delicate’ floral scent that would help conceal menstruation. Deodorant tampons joined other vaginal deodorants introduced to the UK consumer market, including sprays, powers, and douches.

In 1970, a feminist organisation called Women in Media (WiM) was established. The group was composed of women who worked in the media and campaigned against sexism within it. One thing they campaigned against was advertising for vaginal deodorants. They group highlighted the adverse and damaging physical reactions that vaginal deodorants could cause. Fragrances can disrupt the vagina’s natural pH balance, which can lead to irritation or infections.

WiM also argued that these products and their advertisement could negatively impact mental health. Adverts used shame, embarrassment around menstruation, and fears of undesirability to sell products. Scented and deodorant tampons have lost popularity in recent years among people who menstruate.

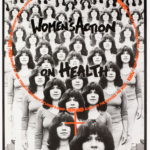

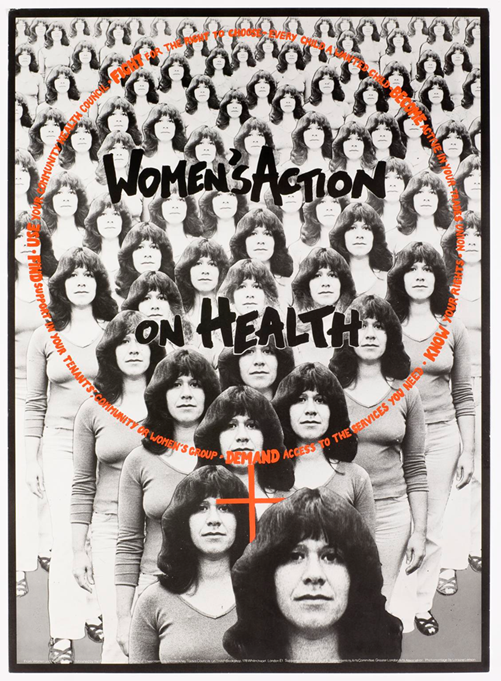

‘Women’s action on health’

This poster advises women to get involved with various groups, including tenant communities, women’s groups, trade unions, and community health councils. Why was collective action so significant for the women’s health movement?

Loraine: Underpinning Left politics at the time was the feeling that ‘together we can change the world’. Collective action was therefore very much the name of the game, and much of this thinking came from feminism. Women had been isolated for so long and were finding their strength through joining together.

One of the ways to take action featured in the poster is ‘Fight for the right to choose – every child a wanted child.’ Was there the sense that reproductive rights were under threat at the time?

Loraine: Women’s reproductive rights have historically been under threat, and it was during the 1970s that the women’s movement really ramped up the struggle for autonomy over our own bodies.

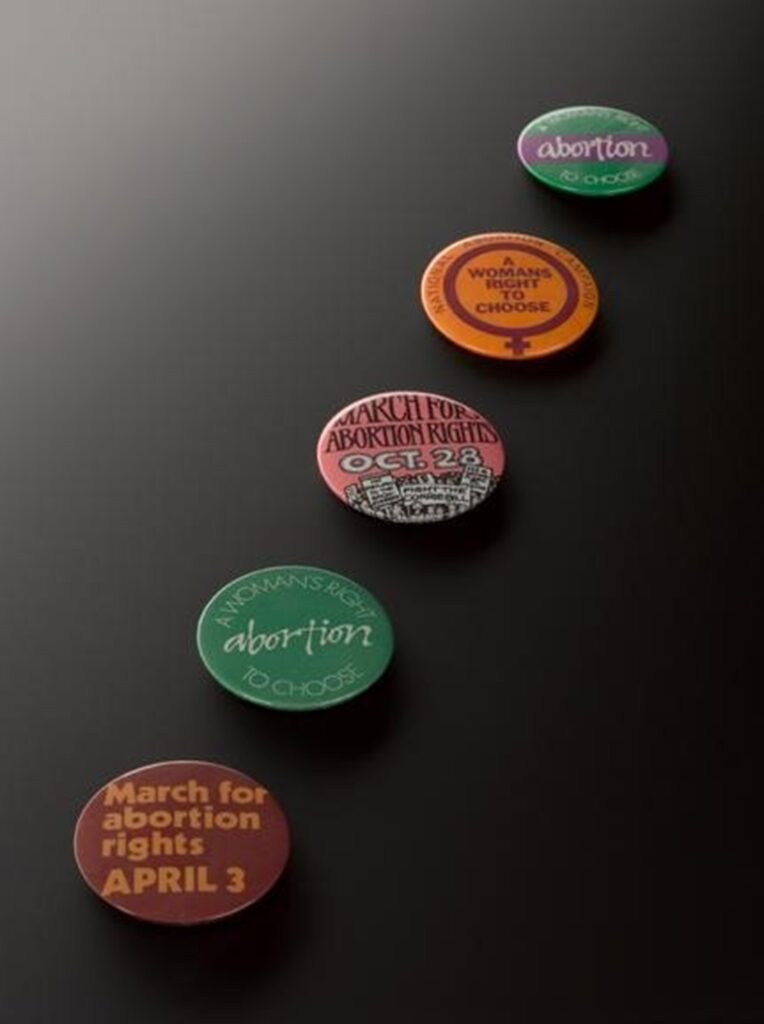

National Abortion Campaign

The 1970s saw many women protesting to protect their reproductive rights. Abortion had been legalised in England, Wales and Scotland in 1967 but only under a set of very specific circumstances. A legal time limit was set at 28 weeks. It had to be approved by two doctors, who had to agree that continuing the pregnancy would endanger the life of the pregnant person or harm their physical or mental health.

In the 1970s and 1980s, several amendments were proposed that sought to restrict access to abortion. The National Abortion Campaign was set up in 1975 to defend the Abortion Act from such attempts. The badges below are from the National Abortion Campaign, and many feature the phrase ‘A Woman’s Right To Choose.’

In 1979, MP John Corrie tabled a bill to reduce the time limit and restrict the grounds on which abortion was permitted. The Corrie Bill was divisive and those against it launched a massive campaign to get the bill thrown out.

The Campaign Against the Corrie Bill brought together feminist organisations, trade unions, health activists and community groups and launched massive demonstrations across the country. The Corrie Bill was eventually withdrawn in 1980 before its Third Reading.

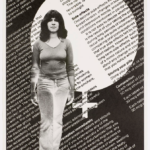

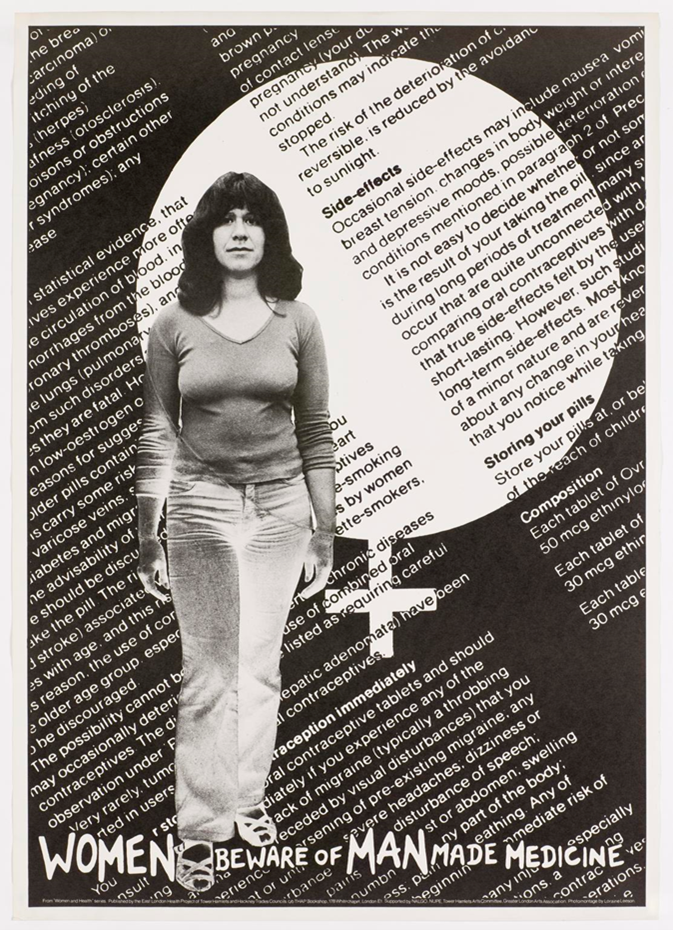

‘Women beware of man-made medicine’

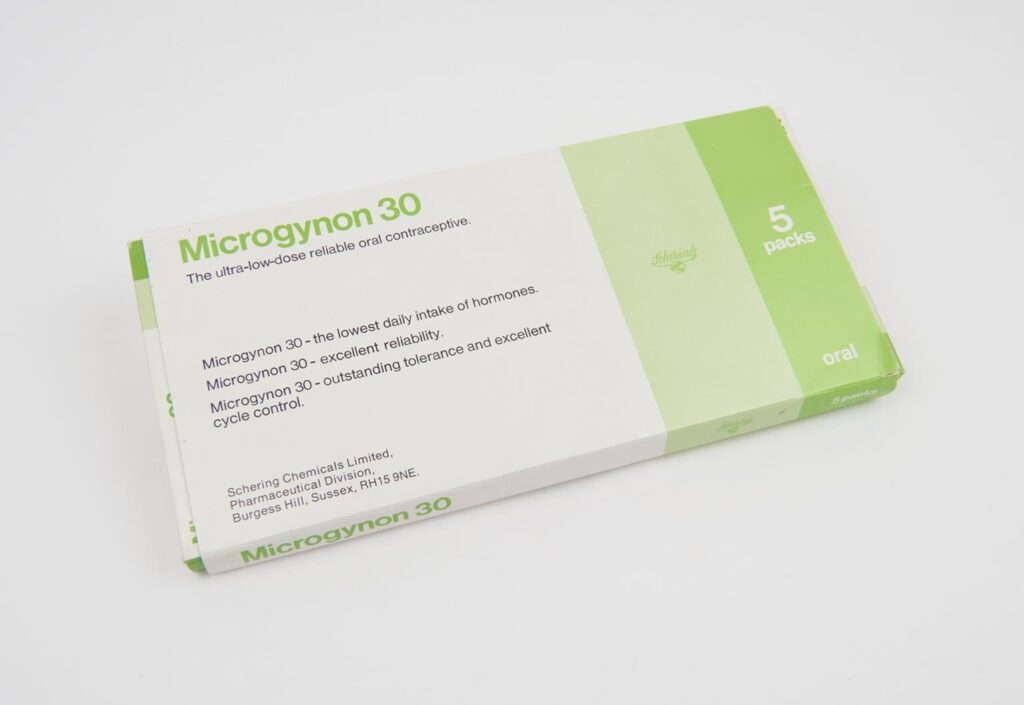

This poster, whose background features the side effects section of a patient information leaflet for the contraceptive pill, tells women to ‘beware of man-made medicine.’ What concerns did women have about the pill at the time and has the perception of the pill change since its introduction in the 1960s?

Loraine: While the pill was initially hailed as truly liberating for women’s sexuality, it also raised a number of questions. Why was it that women remained responsible for reproduction? Why wasn’t similar research being put into a pill for men?

There were also many side effects connected to early contraceptive pills that were borne by women while men enjoyed stress-free sex – a pill developed by men (since women scientists were few), to liberate men, with all the fallout on women!

The contraceptive pill

Credited as a catalyst that heralded the sexual revolution of the Swinging Sixties, the Pill provided the power to determine one’s own reproductive future. It became available for married women in the United Kingdom in 1961 and unmarried women in 1967.

There were many positive impacts of the Pill. By providing a means to delay starting a family until later in life, it enabled users to pursue careers and higher education. It was nearly 100% effective so people could have sex without fearing unplanned pregnancy. Also, it put reproductive control into the hands of women.

However, it was not perfect; taking the Pill opened users up to health risks and side effects. Risks and information were not always communicated to people before it was prescribed. Women’s health groups wanted to raise awareness so that people could make an informed decision about whether to take the Pill or not.

In 1970, the U.S. Senate met with scientific experts to discuss the safety of the Pill. No users of the Pill were invited to talk about their experiences and activists protested that women’s voices were not being considered. In Britain, the same discussions were being had. New medical research had found that users of the Pill who smoked were at greater risk of developing blood clots. A lot of side effects were linked to the high levels of hormones that were found in earlier versions of the Pill, which are no longer prescribed.

In December 1969, the UK placed a restriction on doctors so that they could only prescribe pills with less than 50µg of oestrogen. This significantly lowered the risk of cardiovascular complications. Patient information leaflets were also introduced to packaging to inform users of any side effects.

Researchers have developed safer, lower dose formulations of the Pill. Although conversations around the merits and drawbacks of hormonal contraceptives continue, the Pill remains a safe and popular form of reversible contraception in the UK.

CONCLUSION

The Women in Health posters touched upon the concerns of activists in the Women’s Health Movement in the 1970s. This movement marked an important shift in the history of medicine, raising awareness on issues of gender bias, sexual and reproductive healthcare and bringing them into the public consciousness.

Almost half a century on, conversations about these themes are still being had. In recent years, lived experiences of abortion, contraception, menopause and menstruation have been shared in the media to bring awareness to issues in healthcare and dedicated communities have formed to offer support and fight for change.

Discover more about the origins of the East London Health Project in our previous blog post, or read this deep-dive other posters produced for the project.