In these days when many of us are self-isolating, the idea of going to a pseudo-research facility-come-holiday camp to be willingly infected with a cold seems extraordinary.

But for over 30 years, thousands volunteered in experimental trials at the Medical Research Council’s Common Cold Unit to help find a cure for the common cold.

Colds are caused by viruses, and it is a virus that is currently causing the deadly infectious disease COVID-19 (or to give it its full title, coronavirus disease 2019).

While the word coronavirus is being used to describe the current outbreak, it is in fact the name for a family of viruses.

It was through the research of David Tyrell, head of the Common Cold Unit, and virus-imaging pioneer June Almeida, that the first coronavirus was identified and imaged in the 1960s.

Opened in 1946, the Common Cold Unit was set up in a former military hospital near Salisbury. Its purpose was to learn more about the micro-organisms that caused our everyday snuffles, and whether they could be stopped (this article includes images from the Unit).

This knowledge might reduce the economic cost of days lost to sickness caused by colds (which now feels somewhat overshadowed by the impact of COVID-19).

It was from one sample of nasal washings, collected from a Surrey schoolchild with a cold in 1960, that David Tyrrell began to suspect a virus they hadn’t seen before might be at work.

Tyrrell wondered if the virus could be visualised by an electron microscope. Samples were sent to the best electron-microscopist in Britain at that time: June Almeida.

Almeida worked at her laboratory in St Thomas’ Hospital in London (which later treated Prime Minister Boris Johnson).

I first became aware of June Almeida and her remarkable story when I discovered her simple virus models and research materials in the Science Museum Group Collection, and later through meeting her family.

The daughter of a Scottish bus driver, Almeida left school at 16 with little formal education but went on to get a job as a laboratory technician in histopathology at Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

After moving to Canada, it was at the Ontario Cancer Institute that Almeida developed her outstanding skills with an electron microscope.

Almeida was the first person to visualise the rubella virus that causes German measles and went on to pioneer a method to better visualise viruses by using antibodies to aggregate them.

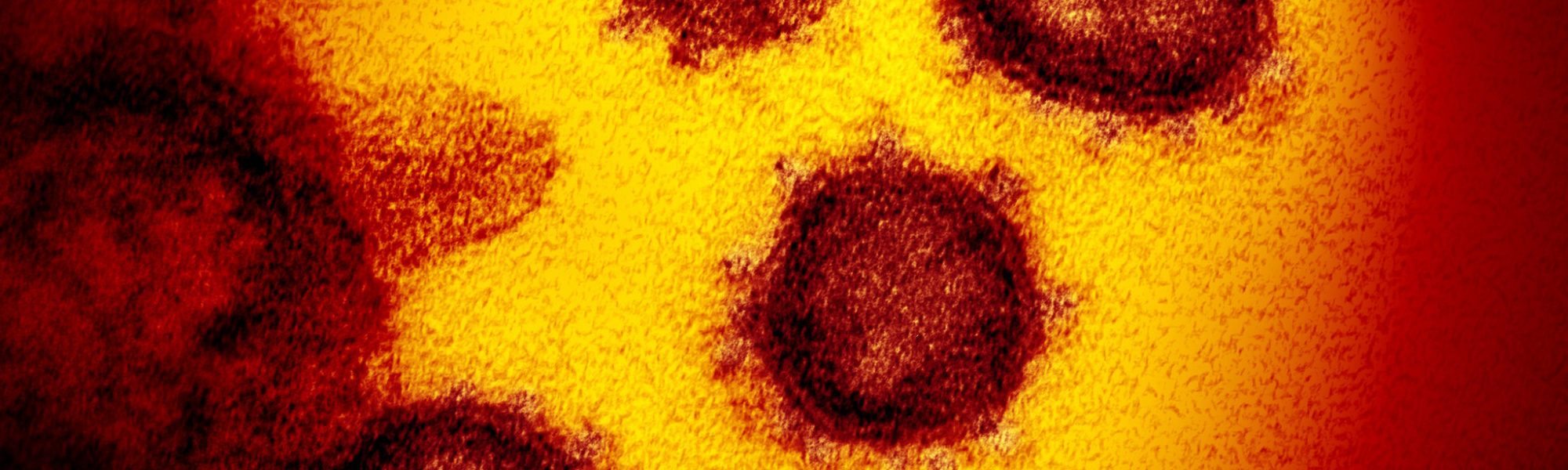

Looking at the samples sent to her from the Common Cold Unit using a transmission electron microscope, Almeida was able to see virus particles with a distinctive crown (or corona), something no-one else had seen before.

Almeida and Tyrrell called the virus a coronavirus, the name now used for this family of viruses.

They published the first photographs of a coronavirus in the Journal of General Virology in 1967.

The Common Cold Unit also studied how the viruses could be transmitted.

One experiment puts into context the critical need for social distancing and personal protective equipment (PPE) today.

The experiment was conducted by James Lovelock of Gaia theory fame who worked at the Common Cold Unit early in his career. Lovelock built a device that trickled fluorescent dye from the nose of one of the laboratory staff.

After playing cards with the device running, the lights were turned off and a fluorescent lamp switched on. The dye was found on their fingers, the cards, table and other parts of the room.

What made the Common Cold Unit more extraordinary than most research institutes was the extensive use of volunteers in trials.

In the isolation of the Salisbury countryside, scientists could examine volunteers in quarantine, closely observing and monitoring the effect of colds.

Volunteers responded to adverts that made participating sound like a holiday: “Free 10 Day Autumn or Winter Break: You May Not Win A Nobel Prize, But You Could Help Find a Cure for the Common Cold.”

Every two weeks 30 volunteers would take part in a double-blind trial – a trial in which neither the researchers nor the volunteers knew whether they had been given infectious material or a placebo to act as a control until later.

Volunteers would stay isolated in their allocated huts for ten days and be monitored closely for symptoms. During their stay, volunteers had three cooked meals a day and lived in a warm furnished hut with one or two others. Many came back year after year.

We have a very good idea of what life was like at the Common Cold Unit.

When the institute closed in 1989, a team from the Science Museum collected a huge number of items from the unit, everything from the walls, ceiling and door of a volunteer’s hut, down to the games they played, books they read and the tea and coffee jars found in the volunteers’ kitchen.

Now part of the national collection, these items and the clues they contain reveal that not every volunteer found the isolation easy (something I think we can all relate to now).

Despite the books, boardgames and a dartboard collected to demonstrate how volunteers passed their time, a desk from a volunteer hut covered in ribald graffiti reveals an insight into the boredom some individuals faced who passed through the trials.

The Science Museum team also collected many of the research tools that David and his colleagues used to study the common cold viruses, including a nozzle for recreating sneeze droplets, snotty tissues collected to examine viruses and the gown and mask the researchers used.

While scientists are hopeful of finding a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 in the near future, it became clear to Tyrrell and others that a cure for the common cold would not be possible due to the large number of viruses responsible.

After 43 years of coughs, sneezes and runny noses, the Common Cold Research Unit closed its doors in 1989.

Whilst the research unit was unconventional in its extensive use of volunteers, it serves as a useful reminder that the race to curb the effects of COVID-19, and progress of medicine in general, relies on the altruism of volunteers willing to participate in research and trial new therapies.

This is the case with individuals who have signed up to be part of the newly launched trial at Oxford University and volunteers are integral to the safety and efficacy testing of any new vaccine.

The specific virus that has caused COVID-19 is called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The global effort to identify and visualise this strain of coronavirus is a critical part of the scientific research that will hopefully lead to treatment and eventually a vaccine.

In February 2020 a team used cryogenic electron microscopy to map the ‘corona’ protein spikes on SARS-CoV-2. Other researchers have discovered how the virus uses its spikes to infect human cells which could be useful in designing treatments to block this action.

Reflecting on how the Science Museum Group preserved the work of June Almeida, David Tyrell and the Common Cold Unit provides an interesting comparison to the extraordinary collecting challenge our curators face today.

On the nation’s behalf we aim to represent for posterity the vital work of scientists and healthcare workers striving to save lives as well as recording COVID-19’s impact on everyday life.

Collecting COVID-19 ethically, broadly and from a distance, is underway right now for the Science Museum Group Collection.

Watch this space for further stories connected to collecting the historic pandemic we are all living through.

When the Science Museum re-opens, you can explore June’s story through a large-scale animation in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries.