The majority of video games back in 1984 looked very different to the current big-budget tiles that we see across our screens today. Arcades were still very popular around the world, and video games tended to follow the same pattern: they were designed to be short, competitive and engaging, enticing gamers to play another round to compete for points and high scores (think of Pong or Pac Man).

But what if a game could be more than just scrolling screens of enemies? What if a game could contain an entire universe to explore at the players’ fingertips…

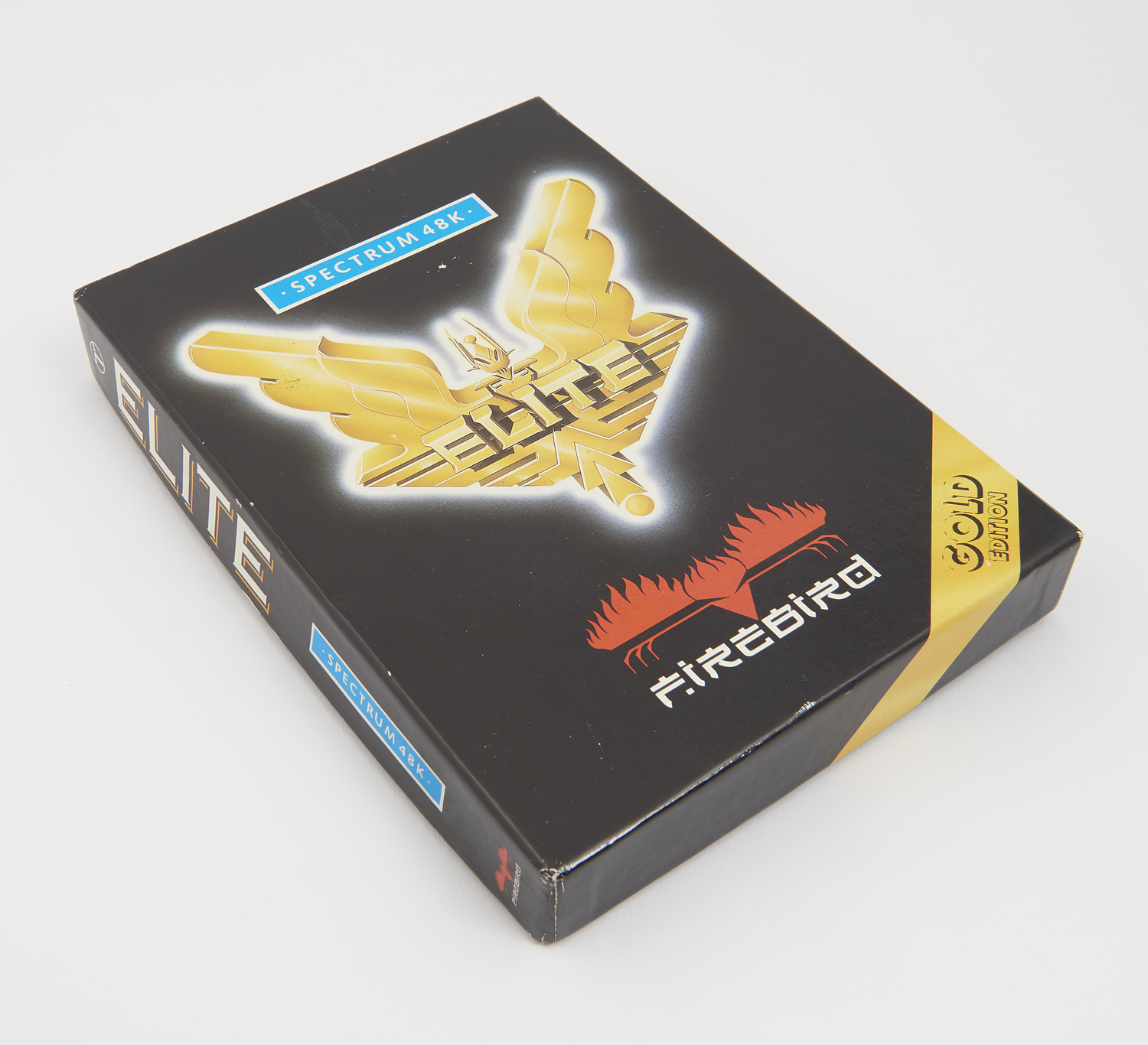

Calling Elite ambitious is somewhat of an understatement. In terms of both visuals and gameplay, British developers David Braben and Ian Bell wanted to challenge the norm of how video games looked and played. The constraints of hardware at the time meant that most games stuck to the existing recipe of 2D animated sprites on static backgrounds.

Space games were already popular, with titles such as Space Invaders and Galaga allowing players to move their pixelated ship left and right across the screen in order to protect Earth from an alien invasion.

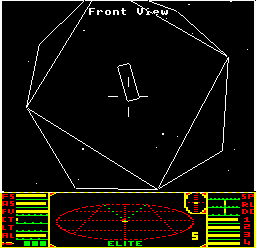

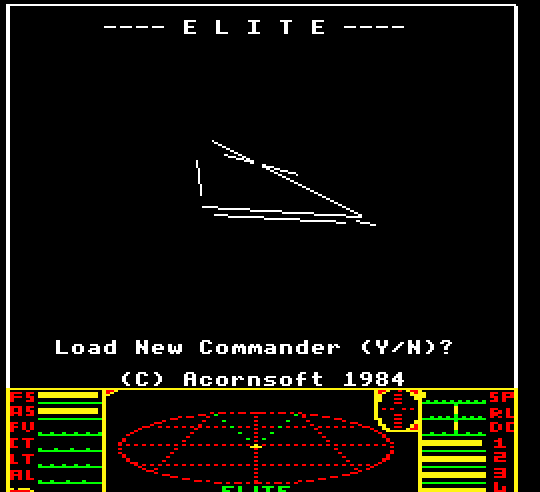

But what Braben achieved with his early prototype was the ability to draw 3D ships using wireframe graphics, simulating intergalactic exploration in three dimensions. Using the black screen as the dark background of space, the outlines of ships and planets could be rendered using lines and then navigated by the player, piloting their own ship, allowing for complete 360 degrees of movement. These early 3D graphics offered a fresh perspective for gamers and helped to move the industry towards three-dimensional polygons instead of 2D pixels.

But it wasn’t just the way that Elite let players see space which was revolutionary, but the way that it let them experience it. The game wasn’t about beating the high score, but instead gave players a universe to explore and the options to do it in their own way – what is known today as an open world game.

Players could engage in interplanetary trade, piracy, bounty hunting, asteroid mining and discover new worlds following their own play style. There was no end goal. No way to win. Elite was one of the first truly open world games and beyond the technical achievements, this is one of the biggest legacies that the game left behind: that a new title could come along and challenge people’s perceptions of what a video game could be.

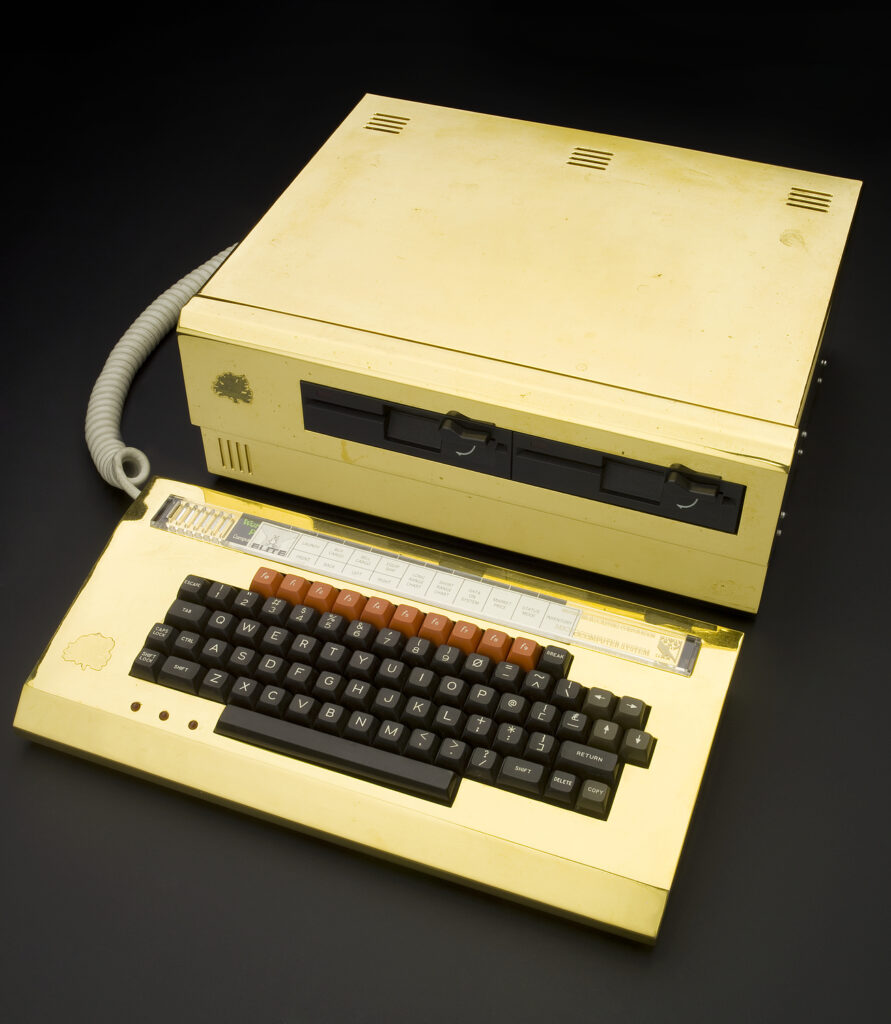

Squeezing all this groundbreaking experience within the small memory available on the BBC Micro console was a feat of technical achievement. With the entire game needing to be reduced to a smaller size than a modern Word document, Braben and Bell made their vision a reality by utilising procedural generation.

This allows for the game to use mathematical algorithms to generate the details of each planet as the players encounters them, instead of having to individually store every ship and every planet in its memory. Procedurally generating content is something frequently seen in modern games, such as Minecraft and No Man’s Sky, where players are given the freedom to explore vast, open worlds.

Elite paved the way out of necessity: with eight galaxies to explore, each containing 256 different planets, this expansive universe was uncharted territory for developers and gamers alike. Following its initial release on the BBC Micro, the game was ported across to other consoles including the Commodore 64, MSX, ZX Spectrum and Apple II.

The success of Elite spawned several sequels, including Frontier: Elite II in 1993 and Frontier: First Encounters in 1995. The most recent entry in the series, Elite Dangerous, launched in 2014, 30 years on from the original, making it one of the longest running game franchises in history.

Original developer David Braben remains as the President and Founder of Frontier Developments, based in Cambridge. In addition to the Elite franchise, the studio has also developed games in the Jurassic World, F1 Manager and Planet Coaster series.

Elite was one of the most popular games developed on the BBC Micro, a system which helped to inspire a generation of people to get into coding and programming. Want to experience the BBC Micro first hand? Head down to Power Up at the Science Museum in London or at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester and play your way through five decades of gaming history across 150 consoles.