Given that cases of COVID-19 are climbing across Europe, and more than 1.3 million deaths worldwide, the Imperial College London team behind the challenge trials believes they will accelerate the development of novel drugs and vaccines and cut risks.

Even so, given that SARS-CoV-2 has few proven treatments, the prospect of deliberately infecting people — even those at low risk of developing severe disease — is uncharted medical and bioethical territory. Some scientists are concerned that these challenge trials may be unethical.

I talked to Prof Peter Openshaw, co-investigator on the study and Director of the Medical Research Council-funded Human Challenge Consortium (HIC-Vac) and to lead researcher Dr Chris Chiu, also of Imperial College London about the first-of-its-kind ‘human challenge trial’.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS OF CHALLENGE TRIALS?

Scientists worldwide are trying to compress years of vaccine development into months. The effort is unprecedented, with 54 vaccines in clinical trials on humans. Last week, encouraging news was reported by Pfizer/BioNTech, who are developing a new kind of vaccine, known as an RNA vaccine.

Earlier this week, promising results in a trial of another RNA vaccine were unveiled by the US company Moderna.

However, these vaccine trials are hit and miss in the sense that volunteers receiving the vaccine may not be naturally exposed to the virus. In the case of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, it was tested on 43,500 people in six countries to yield results that were based on only 94 COVID-19 cases.

Much is still unknown about how long protection lasts (though there is evidence one form of immunity might last at least nine months in most people), whether vaccines work as well in higher-risk people such as the elderly, and what vaccines can be made that are suitable for impoverished settings that do not have a refrigerated “cold chain”.

Because a human challenge study deliberately infects volunteers it should be possible for scientists to more quickly establish efficacy. By one estimate, speeding the development of COVID-19 vaccines by one month would avert the loss of 720,000 years of life and prevent 40 million years in poverty, mostly in lower-income countries.

Among the expert reaction to the announcement, Prof Julian Savulescu, Co-Director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities, University of Oxford, said: “It is surprising challenge studies were not done sooner. Given the stakes, it is unethical not to do challenge studies.”

The benefits were also outlined by Deputy Chief Medical Officer Jonathan Van-Tam: ‘First, for the many vaccines still in the mid-stages of development, human challenge studies may help pick out the most promising ones to take forward….for vaccines which are in the late stages of development and already proven to be safe and effective through Phase III studies, human challenge studies could help us further understand if the vaccines prevent transmission as well as preventing illness.’

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

The study aims to recruit volunteers from younger age groups, who are at lower risk but ‘there are albeit rare cases of severe and/or long-lasting disease in this group for which we have no clear explanation,’ commented Dr Stephen Griffin, University of Leeds. “As an effective rescue therapy does not yet exist for SARS-CoV2, there is a serious ethical dilemma.”

An American team wrote recently that the severity of COVID-19, and the lack of a cure or effective treatment, make it unethical to do a challenge trial for the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: ‘Vaccine trials aiming to undertake risky and uncertain steps in human subject research—particularly those that depart from standard approaches to protection of subjects in human challenge studies—risk further exacerbating increasing levels of public mistrust related to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development.

…At this critical moment in the response to the pandemic, it would do more harm than good.”

The image was captured and colorized at NIAID’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) in Hamilton, Montana.

Given the predicted rise in anti-vaccination views, Prof Openshaw said he understood this anxiety: ‘With the vaccines under test, it is absolutely vital this is done properly, despite the global emergency, and no shortcuts are made to compromise safety. I should add that the vaccine developers have done an excellent job in signing an agreement that says they will not be pushed into bypassing safety regulations. That is the last thing that anyone wants is to see.”

When it comes to human challenge studies, the last thing we want is for anyone to come to harm and we have done everything we can within the protocol to ensure the lowest possible risk. Indeed, I would say there is almost an ethical imperative to do the studies if they can be done safely because the potential human benefit is so great.”

“Our number one priority is the safety of the volunteers,’ added Dr Chiu. “My team has been safely running human challenge studies with other respiratory viruses for over 10 years. No study is completely risk-free, but the Human Challenge Programme partners will be working hard to ensure we make the risks as low as we possibly can.”

Regarding the comment from American scientists, he added: ‘There are diverse attitudes worldwide, so while I understand their point of view it is not necessarily held by everyone. The benefits still outweigh the risks and accepting the earliest vaccines that emerge is not going to be enough. Better vaccines are still going to be needed and a recent Wellcome Trust study showed more concern about making the vaccine available to the largest number of people.”

HAVE YOU GOT VOLUNTEERS?

‘Ethical approval is a multi-stage process, and we are just about to get approval to start the screening,” said Dr Chiu. ‘I hope that we will be able to start recruiting around late November.’

They will recruit up to 90 volunteers. To minimise the risk they face, the volunteers will be young, between the ages of 18 and 30, with no previous history or symptoms of COVID-19, no underlying health conditions, and no known adverse risk factors for COVID-19, such as heart disease, diabetes or obesity.

‘Volunteers will be informed to the hilt of the possible risks of the challenge trial, along with the risks they would face if they were naturally infected at a student party or social event, as so many of their peers have been exposed,” said Prof Openshaw. “By doing it in controlled circumstances, under medical supervision, they are less likely to come to harm – we have to look at the trial in that context.”

WILL TESTS ON YOUNG VOLUNTEERS BE RELEVANT TO OLDER AT-RISK GROUPS?

Perhaps the main limitation is that the challenge studies can ethically only select healthy adult volunteers – not children or the elderly, or those vulnerable groups with diabetes, hypertension, chronic heart, lung, kidney disease, or pregnant women or immunocompromised people,’ commented Dr Julian Tang, University of Leicester. “The interpretation of such studies will, ironically, be only applicable to those who least need the protection.”

Dr Chiu responded that young healthy adults do indeed have the best immune response but, by the same token, that will make it easier to weigh up the protection against disease afforded by a vaccine. ‘They are the benchmark,” he explained.

“If your vaccine does not induce any protection in young healthy adults then it is not going to work in older adults, people with problems with their immune system, or babies with immature immune systems,” he said. “If that’s the case, you don’t waste time and resource on those vaccines that are unlikely to work, which is ethically questionable. Also, if you do understand what kind of immunity protects you, you want to study young health adults because they are the ones who are best protected.’

WHO IS BACKING THE CHALLENGE TRIAL?

The Government’s Vaccine Taskforce.

With Government support of £33.6 million, it is an effort by Imperial College London, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, a Dublin-based commercial clinical-research organization called Open Orphan and its subsidiary hVIVO, a clinical company with expertise in recruiting volunteers for challenge trials, and the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

A further £19.7 million will scale-up capabilities to process blood samples from the research. ‘We have an alignment of all the planets to uniquely position the UK to be the first in the world to do these studies,’ said Prof Openshaw.

WHO REGULATES THE TRIAL?

As with all clinical studies, the proposed research will be considered by regulators including the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the NHS Health Research Authority through an expert research ethics committee.

The dialogue with the ethics committee is ‘very useful’ to hone the study, said Prof Openshaw.

WILL VOLUNTEERS BE PAID TO BE INFECTED?

They will be compensated for the two weeks they will spend in the study, typically around £4,000.

Some argue this could be a motivation to take an unnecessary risk, while others would argue that it is a reasonable compensation for giving up two weeks of their time.

The company hVIVO will screen volunteers to ensure they want to do it for the greater good. Dr Chiu said this issue “has been debated by ethicists for years and years. You need to be aware of the potential for overly incentivising people but also that they are responsible adults capable of making their own decisions.

Ultimately, people are giving up their time when they could be working or earning money, so it is fair to give them compensation. How much they should be paid boils down to the living wage or the market rate for similar kinds of studies. The final figure also has to be agreed upon by the ethics committee.’

WHEN WILL THE TRIAL START?

If approved by regulators and the ethics committee, the studies would start in January with results expected by May 2021.

WHERE DID THEY GET THE SARS-COV-2 VIRUS?

The team isolated the virus with the help of the ISARIC consortium, which studies hospitalised patients at 200 UK hospitals. ‘At the time we were looking for the virus, the big outbreak was in Bolton, Greater Manchester’ said Prof Openshaw.

When selecting viruses to grow, they were also keen the sample came from a patient who was free of other infections that would otherwise complicate matters, for instance by contamination with other pathogens.

The Imperial team selected 30 isolates from COVID-19 patients in Bolton, then narrowed that down to three that seemed typical and grew well in cells, with the amount of virus in the fluid around the cells amplified as it was passed through more cells.

‘Most coronaviruses don’t grow very well in standard cell lines, that is human or animal cells that we grow in the lab,’ said Dr Chiu. ‘However, SARS-CoV-2 is much more robust and rapidly growing than coronaviruses that cause the common cold.”

The job of turning the selected virus into samples for challenge trials will be done by a team led by Prof Judith Breuer in a clean room in Great Ormond Street, London, where viruses are routinely turned into ‘vectors’, so they are made safe and genetically altered for gene therapy.

Of the three strains, one has now been selected to infect cell lines, said Dr Chiu, adding ‘that final stock has to be extensively tested as well, just to make sure we know exactly what we are putting into the volunteers.”

As a result of its global spread, the virus now comes in different strains, for instance, there is the ‘cluster 5 variant’ linked with an outbreak in mink. ‘People are very concerned when they hear that the virus is mutating. Of course, it is mutating, that’s what viruses do,’ said Prof Openshaw.

In the longer term, they may have to consider challenge trials with new COVID-19 strains, he added. “We have to take that into account. However, the spike protein (the protein on the exterior of the virus that it uses to invade human cells) is still maintaining its basic structure and in general, the immune response is pretty broad so small changes are unlikely to negate the impact of future vaccines or monoclonal antibodies developed as treatments.’

HOW WILL THE VIRUS BE ADMINISTERED?

Evidence to date suggests COVID-19 spreads when relatively large spittle droplets that are laden with coronavirus – emitted during conversation, shouting, or singing for example – settle in the nose, rather than penetrate deep into the lungs.

Another route of transmission is by touching a contaminated surface, then rubbing one’s eyes, along with being in an enclosed space with an infected person, when smaller particles ‘are suspended like a gas,’ said Prof Openshaw. ‘However, though important with influenza, we think it is less so for SARS-CoV-2. So, by giving it as nasal drops, we believe that this will be the best balance between mimicking natural transmission and minimising the risk of virus going down into the lungs.’

The drops consist of “a clear liquid which will also have some sugar, sucrose, which stabilises the structure of the virus, so when it is administered to people they might be able to taste a little bit of sweetness,’ added Dr Chiu.

They decided not to administer the virus by inhaling it into the lung in fine particles because there is evidence that it causes more severe illness, he added.

The route of admission does matter: an earlier study in influenza found large droplet inoculation may produce a different infection/disease than more natural aerosol inhalation.

WHERE WILL THEY DO THE TRIAL?

Volunteers will be housed in the high-level isolation unit of the Royal Free Hospital in north London, near the infectious disease wards, in a facility that was custom built but is not currently in use. To create this 19-bed facility would normally cost around £1 million per bed.

Studies there will be conducted under strict conditions: these include a controlled entrance to the facility, decontamination of waste, and a dedicated laboratory for carrying out tests. All the air leaving the unit is also cleaned.

Medics and scientists will be on hand 24/7 to carefully examine how the virus behaves in the body and to ensure volunteer safety.

WHAT DOES THE CHALLENGE TRIAL CONSIST OF?

In the first stage, known as a ‘virus characterisation study’ a small number of participants will receive a very low dose of the SARS-CoV-2 ‘challenge strain’.

If none or a few of the participants become infected, the researchers will seek permission from the independent safety monitoring board to expose participants to higher doses. This process will be repeated until researchers identify a dose that infects most of those exposed.

In the second phase, once an appropriate dose has been identified, the challenge trial will be used to study how vaccines work in the body to stop or prevent COVID-19, to look at potential treatments and study the immune response.

Typically, in some trials, 40-50 participants will receive a placebo injection instead of a vaccine, though head-to-head trials comparing two or more vaccines could be run.

If vaccine trials then take place, Open Orphan will recruit more participants.

WHAT HAPPENS DURING THE TRIAL?

A range of samples – blood, swabs, and so on – will be taken and shared with a variety of groups – both academic and commercial – for analysis.

Because the trials are backed by the Vaccine Taskforce, Dr Chiu said it is important that all the main immunological tests and assays are run the same way, with tight process and quality control.

There will also be more specialised tests for basic research, for example, to look at the nature of T cells induced by infection and immune responses in the lining of the nose.

WHAT ARE THE COMPLICATIONS?

Pre-existing antibodies to other common cold coronaviruses may be potentially important and confounding – in how people respond to the COVID-19 vaccine.

WHEN WILL VOLUNTEERS RETURN TO NORMAL LIFE?

Before leaving the Royal Free clinical facility, volunteers would be required to test negative for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in two separate laboratory tests, highly sensitive to the presence of an infectious virus. Volunteers will be monitored for up to a year after participating in the study.

WHAT CAN CHALLENGE TRIALS TELL US ABOUT THE VACCINES?

When compared with campaigns to test a vaccine on front line health workers, for example, challenge studies are better at identifying the detailed immune responses that predict whether a vaccine is likely to work or not.

‘That is one of the great strengths of this study,’ said Dr Chiu. ‘you can be much more confident that the results you observe are as a result of the infection or vaccine and not due to other effects or exposures.’ That, he said, could lay the groundwork for fresh insights into the disease and help develop later-generation vaccines.

Human challenge studies also make it possible for scientists to compare the efficacy of vaccine candidates by testing them side-by-side to establish which is more effective.

Although major trials can show a vaccine works, it is not always obvious how they work, so head-to-head trials can help reveal the protective mechanisms and ‘correlates of protection’. ‘The core question is how do we know what we are measuring in the immune system is any good at predicting the protection and the only way we can do that is with a deep understanding of the immune system,’ said Prof Openshaw.

In the case of influenza vaccination injections, for example, there is a good correlation between the antibodies in the blood serum and protection, but this is ‘just a correlate,’ said Prof Openshaw. ‘When it comes to live attenuated nasal vaccines introduced for schoolchildren a few years ago, they are protective but don’t produce serum antibodies. We were able to show at Imperial, using nasal fluid samples, that there are antibodies in the nose which are enough to protect you.”

HAVE CHALLENGE TRIALS BEEN DONE BEFORE?

Human challenge studies have been used throughout history and have provided a wealth of information about flu and cold viruses.

Edward Jenner’s famous experiment performed in 1796 of deliberately infecting a boy – James Phipps – with cowpox, and then subsequently infecting him with smallpox could be considered one of the first human-challenge trials.

Over many decades, human challenge studies have played important roles in accelerating the development of treatments for diseases including malaria, typhoid, cholera, and norovirus.

“I am convinced we can do it safely when you take into account the many challenge studies that have been done before,’ said Prof Openshaw.’ ‘Not in the case of COVID-19, but there is a long history of doing this, for example at the Common Cold Research Unit, where they studied aerosolising viruses. ‘

The first job of James Lovelock, who is best known for his Gaia theory, was at the National Institute for Medical Research in North London, working in the department of one of the discoverers of the influenza A virus, Sir Christopher Howard Andrewes, where the memory of the devastating 1918 influenza pandemic was still raw.

After the war, Lovelock was sent to the Common Cold Unit (as the Air Hygiene Unit in 1948) where volunteers were infected with the common cold.

The first coronavirus was identified and imaged at the Common Cold Unit in the 1960s by David Tyrell, head of the unit, working with virus-imaging pioneer June Almeida. Her simple virus models and research materials are in the Science Museum Group Collection.

There is also a long tradition of self-experimentation, for instance by biologist J B S Haldane (1882-1964), who repeatedly putting himself in a decompression chamber to investigate ‘decompression sickness’ (aka ‘the bends’) in divers, famously bursting his eardrums.

He found that even a hole remains, “although one is somewhat deaf, one can blow tobacco smoke out of the ear in question, which is a social accomplishment.”

Barry Marshall – who shared a Nobel prize in 2005 for the discovery that a bacterium, not stress, was the main cause of painful stomach ulcers – became so frustrated by the skepticism of his peers that he even drank a broth of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori to prove his point.

Even when Prof Openshaw was a medical student in the 1970s, ‘we all experimented on ourselves and each other, and with no consent forms. By today’s standards, some were risky.’

One of his mentors, Moran Campbell, underwent an experiment in which he was paralyzed by an injection of curare, except for one forearm, which he had protected with a blood pressure cuff, ‘which allowed him to signal breathlessness, as he lost consciousness.’

He was kept alive with a mechanical ventilator, which was then switched off. Campbell signaled no discomfort for four minutes, then an attending anesthesiologist decided to turn the ventilator back on.

HAS THE HUMAN CHALLENGE TEAM CONSULTED WIDELY?

There has already been ‘structured, organised and thorough engagement’ from the earliest stage with representative members of the public, in the form of surveys and workshops, to help work up the protocols for the ethics committee, said Prof Openshaw. ‘We have found in the past that is absolutely vital for ultimate public acceptability.’

‘We have been doing a lot of public engagement to understand how people feel about this kind of study in general, and in particular, and have looked at specific issues such as diversity and inclusion,’ added Dr Chiu. ‘We hope to present our findings to the ethics committee around the time we start screening, and we will be publishing the protocol and the public engagement findings as well.”

Research suggests that many people were not aware of this kind of study. Once they found out about the details, in general, they were supportive, he said.

Katharine Wright, Assistant Director, Nuffield Council on Bioethics, commented: “Engagement with the wider public is key, as it is important that public concerns are properly understood and addressed from the outset.’

WHICH VACCINES WILL BE TESTED?

The UK pre-ordered six different potential COVID-19 vaccines, of four basic types. This week it also ordered Moderna’s vaccine. At this early stage, no specific vaccine candidates for the human challenge trials have been confirmed.

CAN I TAKE PART?

Anyone interested in registering their interest in future COVID-19 human challenge study research should visit www.UKCovidChallenge.com.

The UK public appears to be sympathetic to this kind of research. In March 2006, trails of a novel drug, called TGN1412, caused multiple organ failure in six men at Northwick Park Hospital, London. Prof Openshaw said that the head of Parexel, the firm that carried out the trial, was surprised to find that more people volunteered ‘She was amazed by the response of the British public.’

IS UK REGULATION MORE RECEPTIVE TO CHALLENGE TRIALS?

Yes. Whether IVF or therapeutic cloning, the UK has decades of experience in blending expert and public consultation to balance the many ethical, moral, and practical issues.

‘The culture here is pragmatic, and people seem to understand the risk-benefit relationship. From the legal and regulatory side as well, the UK tends to be light touch, once safety has been established.’ Said Dr Chiu. ‘That leaves us able to explore more ambitious areas’.

In America, by comparison, this kind of challenge trial would be ‘close to impossible,’ because of regulatory and legislative hurdles, added Prof Openshaw. ‘In this country, there is a framework and culture that is more calm and understanding, and less polarised.’

HOW CAN I FIND OUT MORE?

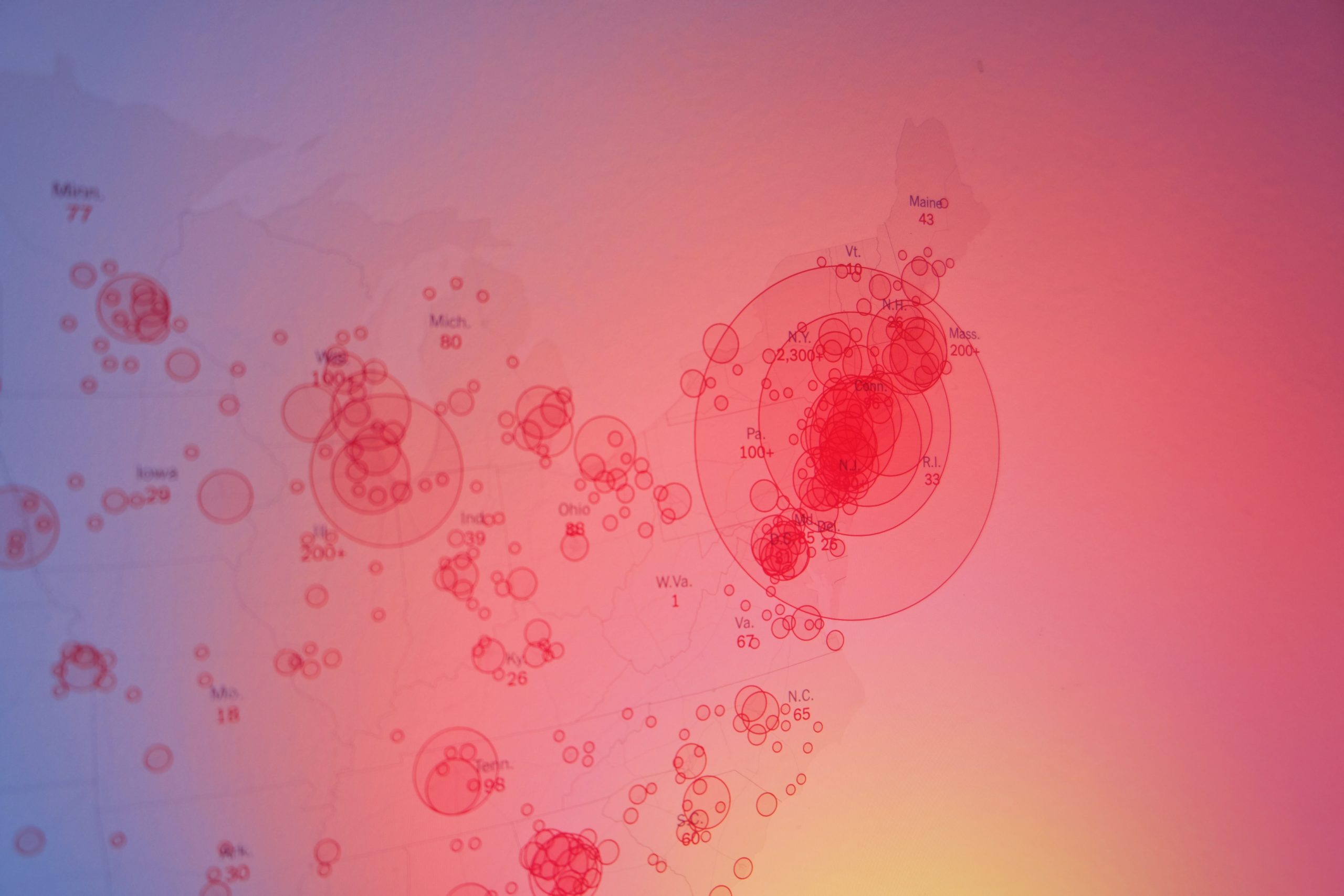

The latest picture of how far the pandemic has spread can be seen on the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center or Robert Koch-Institute website.

You can check the number of UK COVID-19 lab-confirmed cases and deaths along with figures from the Office of National Statistics.

There is much more information in our Coronavirus blog series (including some in German by focusTerra, ETH Zürich, with additional information on Switzerland), from the UKRI, the EU, US Centers for Disease Control, WHO, on this COVID-19 Preview Changes(opens in a new tab)portal and Our World in Data.

The Science Museum Group is also collecting objects and ephemera to document this health emergency for future generations.