The first ever global plastics pollution inventory is published today, revealing the vast scale of uncollected rubbish, and the open burning of plastic waste. The scientists who did the study hope that it will spur new efforts to protect the environment and human health.

The last two centuries have been dubbed the Plastics Age and the Science Museum Group Collection contains many examples, from Parkesine, patented in 1862, and Bakelite, the first fully synthetic plastic developed in 1907, to a beer bottle made of PET (polyethylene terephthalate or polyester) and weathered Lego bricks found on a beach after a cargo was lost overboard in 1997.

To predict how much plastic waste was generated globally along with its fate, a team at the University of Leeds harnessed a form of artificial intelligence, AI, called machine learning, to model waste management in almost 51,000 municipalities worldwide.

The model uses multiple steps to describe the fate of plastic items and when they become waste. At its core is the AI, which uses data from a new, comprehensive and quality assured database on waste in cities to work out the link with indices of socioeconomic development, so that it can predict the waste generated by municipalities for which few data are available.

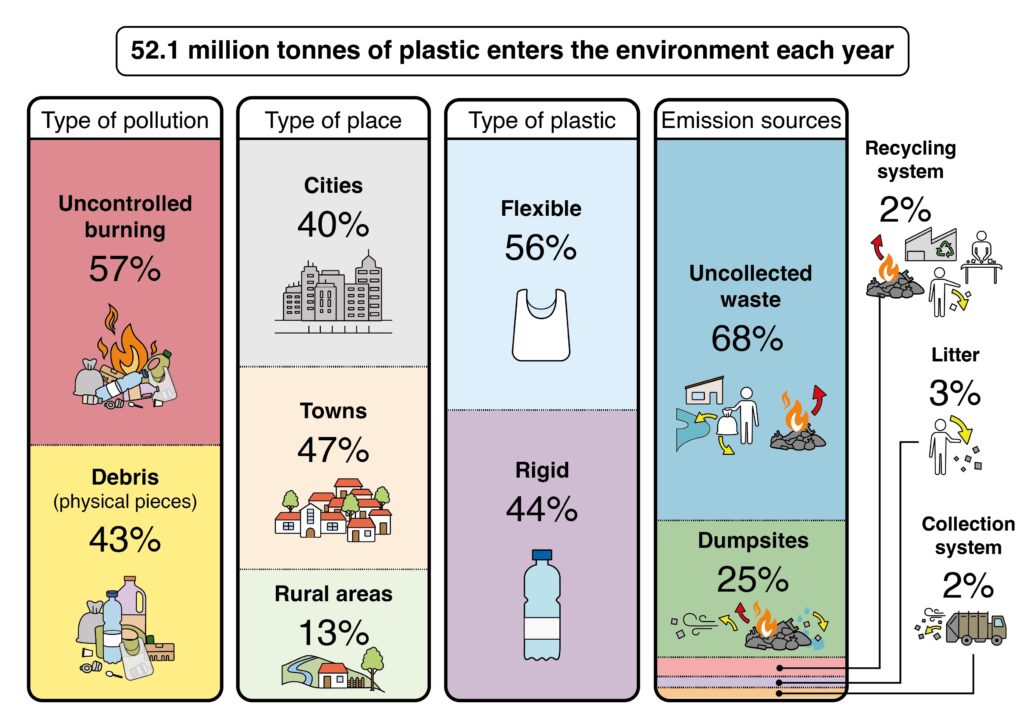

Their study, published today in the journal Nature, calculated that 52 million tonnes of plastic products were not managed and ended up in the environment in 2020. This amount, if laid out in a line, would stretch around the planet more than 1,500 times.

More than two thirds of the planet’s plastic pollution arise from uncollected rubbish because almost 1.2 billion people — 15% of the global population — live without access to waste collection services, which the researchers believe should be seen as a necessity along with water and sewerage.

First author Dr Josh Cottom, Research Fellow in Plastics Pollution at Leeds, said these 1.2 billion people are ‘forced to ‘self-manage’ waste, often by dumping it on land, in rivers, or burning it in open fires.’

He added: ‘The health risks resulting from plastic pollution affect some of the world’s poorest communities, who are powerless to do anything about it.’

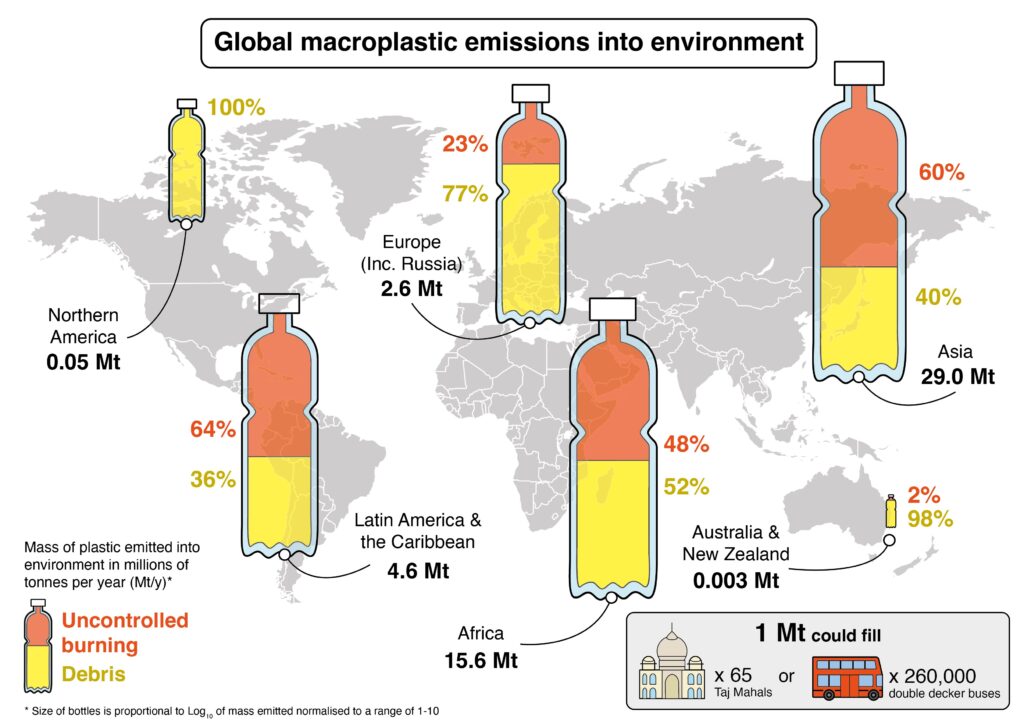

The researchers show that in 2020 alone some 30 million tonnes of plastics — amounting to 57% of all plastic pollution — was burned without any environmental controls in place, in homes, on streets and in dumpsites.

The large mass of waste burned in open uncontrolled fires has not formed a central part of international discussions and yet it comes with ‘substantial’ threats to human health, they say, including neurodevelopmental, reproductive and birth defects, underlining how uncontrolled burning of plastic is at least as big a problem as discarded rubbish.

Dr Costas Velis, academic on Resource Efficiency Systems at Leeds, who led the research, said: ‘We need to start focusing much, much more on tackling open burning and uncollected waste before more lives are needlessly impacted by plastic pollution. It cannot be ‘out of sight, out of mind’.’

While littering is the largest source of plastic pollution in the Global North, uncollected waste is the dominant source across the Global South.

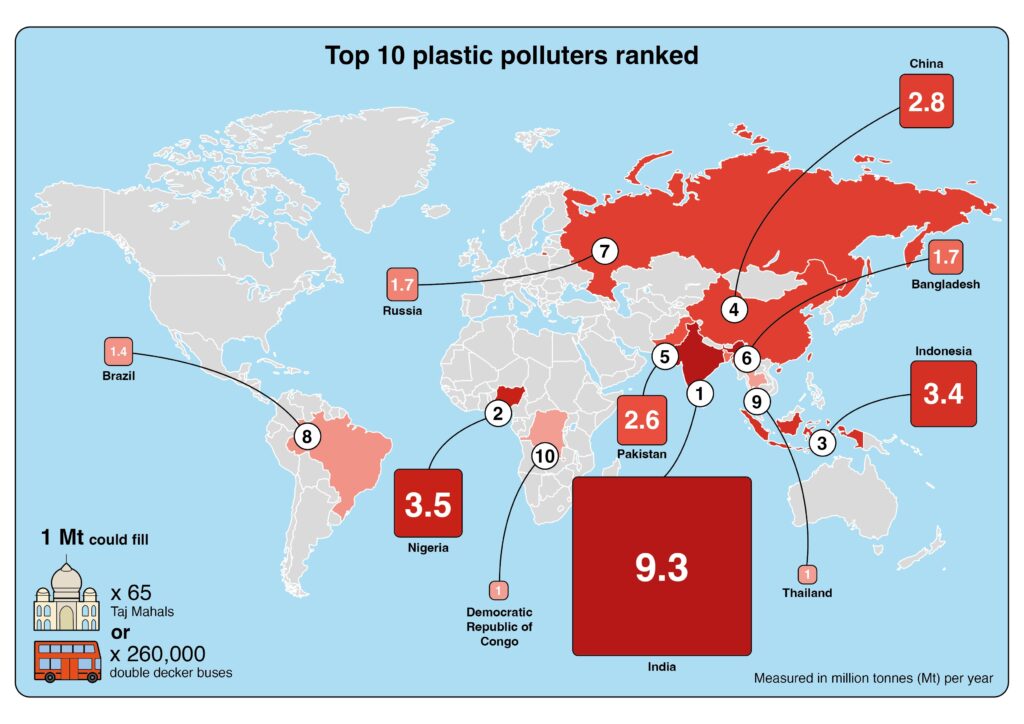

The researchers also identified novel plastic pollution hotspots, revealing India as the biggest contributor — rather than China as has been suggested in previous models — followed by Nigeria and Indonesia.

India generates 9.3 million tonnes of plastic waste— around a fifth of the total amount – because it has a large population, 1.4 billion, much of its waste is not collected, and official waste generation is underestimated, while waste collection overestimated. ‘Delhi in India is the country’s worst municipality (local authority) regarding absolute total emissions for all people and is actually the world’s second worst after Lagos in Nigeria,’ said Dr Velis.

Then come Nigeria, at 3.5 million tonnes, and Indonesia, with 3.4 million tonnes.

China, previously reported to be the worst polluter, is now ranked fourth, with 2.8 million tonnes, because of improvements in collecting and processing waste over recent years.

Russia, the world’s fifth largest emitter on an absolute basis, also has high emissions on a per-capita basis because it is reported to have extremely low levels of controlled disposal. By comparison, the UK was ranked 135, with around 4,622 tonnes per year, with littering the biggest source.

While many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have low levels of plastic pollution, they are hotspots on a per-capita basis with an average 12 kg plastic pollution per person per year, equivalent to over four hundred plastic bottles. By comparison, the United Kingdom currently has the per-capita equivalent of fewer than three plastic bottles per person per year.

The Leeds team is concerned that Sub-Saharan Africa could become the world’s largest source of plastic pollution in the next few decades, because many of its countries have poor waste management and the population is anticipated to grow rapidly.

Each year, more than 400 million tonnes of plastic is produced, and many plastic products are single-use, hard to recycle, and can linger in the environment for decades or even centuries, often fragmenting into microplastics. Some plastics also contain potentially harmful chemical additives which could pose a threat to human health, particularly if burned in the open.

The team hopes that this first ever global inventory of plastic pollution provides a baseline — comparable to those for climate change emissions — that can be used by policymakers to tackle what Dr Velis calls ‘an urgent global human health issue’ with a new, ambitious and legally binding, global ‘Plastics Treaty’ aimed at tackling the sources of plastic pollution.

Ed Cook, Research Fellow in Circular Economy Systems for Waste Plastics at Leeds, commented that: ‘We hope that our detailed local scale dataset will help decision-makers to allocate scarce resources to address plastic pollution efficiently.’